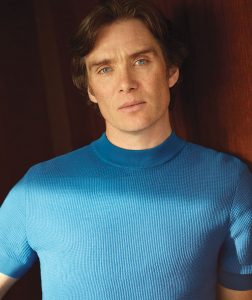

It’s a quiet morning in Ireland – several weeks before a virus swept the world and changed everything – and Cillian Murphy, the 43-year-old actor born and reared in County Cork, is feeling cheery. In an unprecedented turn of events, the Irish republican party Sinn Féin gained 15 parliamentary seats and 24.5 per cent of the popular vote in a recent general election – a massive showing. “We may have ruptured a two-party system, finally, in Ireland,” says Murphy. “It’s the first time the main two parties have been put in their place by this party, Sinn Féin.”

Murphy’s interest in the landscape of Irish politics – and their complicated, sometimes violent history – has played an important role in shaping his film stardom. He’s best known in Hollywood for his star turn as a preening domestic terrorist in Wes Craven’s crackerjack thriller Red Eye, and for his multiple collaborations with Christopher Nolan in Inception,

Dunkirk and, most notably, as the psychotic psychotherapist The Scarecrow in the Dark Knight trilogy. But Murphy’s ties to Irish independent cinema run deep. Living a relatively quiet life in Dublin, he’s something of a proud native son, both onscreen and off.

An aspiring musician who played in a Frank Zappa–inspired funk-rock outfit called The Sons of Mr. Greengenes, Murphy dropped his axe in the late ’90s when he first started seeking acting roles. “My philosophy,” as he puts it, “is to try and do one thing well.”

Maintaining that actors with bands are rarely taken seriously for their musical pursuits, he invested that artistic energy into the study of drama and theatre. Murphy first turned heads in 2005’s Breakfast on Pluto, a fanciful coming-of-age drama about a transgender orphan (Murphy) who, at one point, shacks up with a member of the Irish Republican Army. In 2006, he starred in the critical and commercial smash The Wind That Shakes the Barley, playing a naive country doctor reborn as a resistance fighter enlisted in the civil war that led to the establishment of the Irish Free State. “That was made by a filmmaker called Ken Loach,” Murphy recalls, “who is a political filmmaker. That’s for sure. Naturally, he was making a film about the history of my country, so you have to engage with that. It involved me doing a lot of reading, a lot of research, and finding out stuff I might not have known, or might not have learned in school.”

The IRA and Ireland’s ongoing struggle to buck the yoke of British colonialism also teem at the edges of Peaky Blinders. BBC’s hit period saga stars Murphy as the leader of a rough-and-tumble crime syndicate operating in and around Birmingham, England. Opening in the immediate aftermath of the Great War, the show’s first season sees Murphy’s Thomas “Tommy” Shelby engaging in some arms trading with Irish freedom fighters, among sundry other shady dealings. And as with Barley, the role demanded a great deal of research, which Murphy takes very seriously. “That goes for all my films,” he says. “You have to do your due diligence, to do research about the people or the community that you’re representing.”

The IRA and Ireland’s ongoing struggle to buck the yoke of British colonialism also teem at the edges of Peaky Blinders. BBC’s hit period saga stars Murphy as the leader of a rough-and-tumble crime syndicate operating in and around Birmingham, England. Opening in the immediate aftermath of the Great War, the show’s first season sees Murphy’s Thomas “Tommy” Shelby engaging in some arms trading with Irish freedom fighters, among sundry other shady dealings. And as with Barley, the role demanded a great deal of research, which Murphy takes very seriously. “That goes for all my films,” he says. “You have to do your due diligence, to do research about the people or the community that you’re representing.”

In the case of Peaky Blinders, Murphy spent time digging into the history of post-traumatic stress disorder among soldiers returning from the trenches. PTSD (then diagnosed as “shell shock”) was regarded as much as a moral failing as it was a physiological ailment, which saw many afflicted cruelly ostracized from the communities they were ostensibly fighting to protect. (In Dunkirk, Christopher Nolan’s WW2 drama, Murphy also played a soldier visibly rattled by the terror and sheer sensory overload of mechanized warfare.) “These men were just spat back into society with no counselling whatsoever,” says Murphy. “It was fascinating, and very sad, to have to read about it. It makes a great foundation for a character: someone who has been through the trenches in France, and has witnessed things you could never even begin to imagine, and is a decorated solider. Then he comes back and he’s completely transformed.”

Rakish, cunning, and impeccably well-dressed, Murphy’s Tommy Shelby is an especially compelling entry into the long-running canon of complicated TV anti-heroes. Like Tony Soprano or Breaking Bad’s Walter White, he finds himself among the ranks of what author Brett Martin described as the Golden Age of Television’s “difficult men.” These characters and their respective shows, Martin writes, take masculinity as their subject, tracing “the contours of male power and the infinite varieties of male combat.” But Tommy is no mere charismatic sociopath. His experience in war has, as Murphy puts it, fundamentally changed him: “There’s very much a line in his life. A line after France. It’s brilliantly dramatic, and an excellent genesis of a character.”

Shelby’s turn to criminality feels like a response to the political and social circumstances that shaped him, and not merely a cover for some deep-seated antisocial psychology. Shelby deals with his trauma by drinking and drugging. But more than anything, he feels like a man who has nothing to lose — because he’s already lost everything. “The man that we see at the beginning of the series is a man that’s lost any belief,” Murphy explains. “He’s also lost the fear of dying. It makes him an extraordinary adversary.”

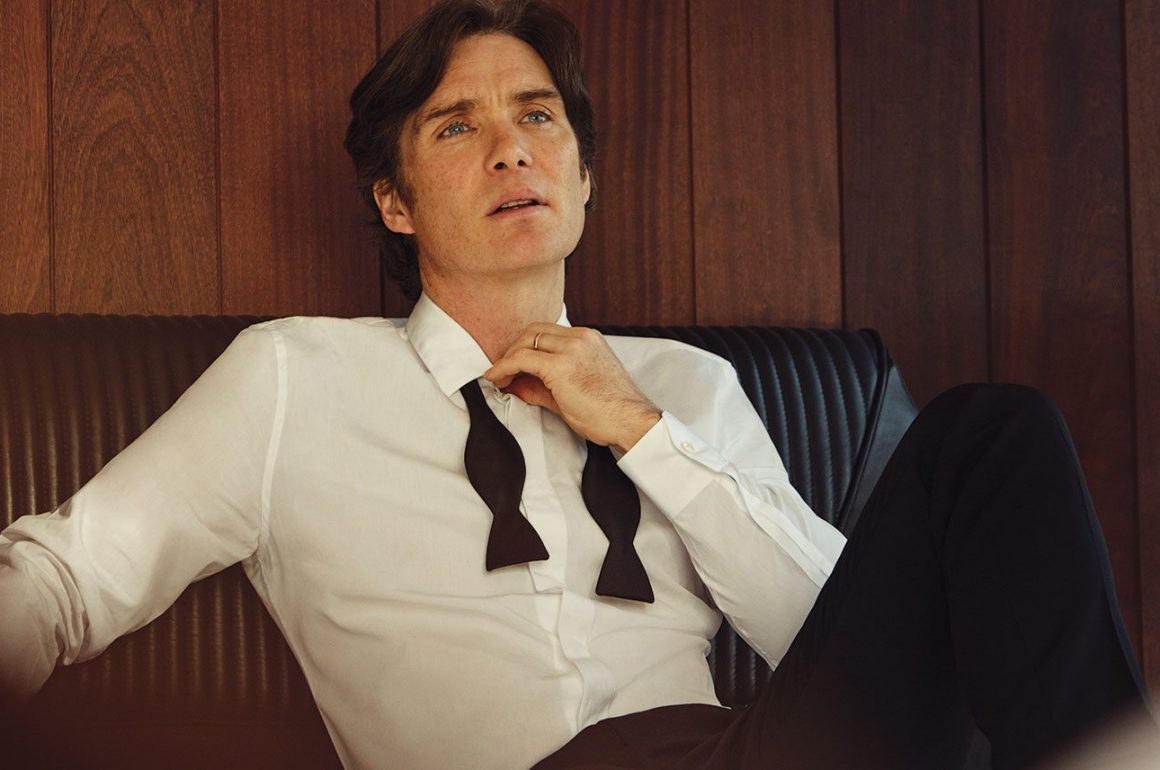

Tommy Shelby may be a walking corpse, dead to the world. But he’s also an exceptionally fashionable one. Peaky Blinders’ namesake gang fights while dressed to the nines: sporting vintage trousers, heavy tweed jackets, bespoke penny collar shirts and, most notably, short-cropped undercut hairdos topped with peaked flat caps.

Combining working-class threads with high fashion, the look has spawned all manner of Peaky Blinders style guides, and seen barbershops inundated with requests for the trademark Blinders ’do. “It had some zeitgeisty moments,” says Murphy of the show’s fashions. “That’s a great compliment to the show.”

“It makes a great foundation for a character: someone who has witnessed things you could never begin to imagine. Then he comes back completely transformed.”

Outside the grimy hollows of 1920s working-class Birmingham, Murphy grew out his hair for A Quiet Place Part II, the sequel to writer–director John Krasinski’s hit 2018 sci-fi horror film, in which he plays a shaggy, bearded survivalist slinking through a post-apocalyptic America. “I’m terribly anti-spoilers,” says Murphy, a bit bashfully. “But I can give you a clue or two. It’s unlike a conventional sequel in that it continues pretty much straight after where the first movie left off, and has the same team and actors in it. With a few additions, myself included.”

Outside the grimy hollows of 1920s working-class Birmingham, Murphy grew out his hair for A Quiet Place Part II, the sequel to writer–director John Krasinski’s hit 2018 sci-fi horror film, in which he plays a shaggy, bearded survivalist slinking through a post-apocalyptic America. “I’m terribly anti-spoilers,” says Murphy, a bit bashfully. “But I can give you a clue or two. It’s unlike a conventional sequel in that it continues pretty much straight after where the first movie left off, and has the same team and actors in it. With a few additions, myself included.”

Not exactly top-secret intel, to be sure. Yet even this scant, spoiler-free description calls to mind Murphy’s work in director Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later, a film that (for better or worse) helped inaugurate the ongoing zombie revival in contemporary pop culture. “I suppose there is some thematic overlap,” Murphy admits. “But it’s very different…Clearly I do well in apocalypses, it seems!”

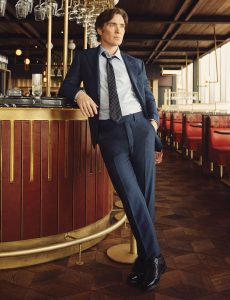

Still, if there’s a certain gloominess to much of Murphy’s work — from 28 Days Later through to Nolan’s gritty Batman reboots and the postwar bleakness of Peaky Blinders — it hasn’t much affected the actor himself. He keeps a quiet ife, far away from the hustle-bustle of Hollywood, which he insists remains unchanged despite the fame Blinders has brought him. He lends his celebrity cachet to a variety of social and political causes, from helping engage young voters in Ireland to supporting the rights of labourers and trade unionists. He’s spoken passionately about Brexit and how it’s yet another attempt to “hold Ireland to ransom.”

Excited by the shifting tides in his home country, the result of both long historical struggles and recent battles around Ireland’s relationship to the European Union, Murphy seems cautiously optimistic about the future of the nation, and the prospect of a unified Ireland. “It will definitely happen in my lifetime,” he asserts. “It will take compromise on both sides. But there will be a referendum. And the people will decide — North and South…We need a strong government here. So, fingers crossed.”

Whether playing the cunning Tommy Shelby, an industrious orphan, an IRA martyr, or any one of his hardscrabble post-apocalyptic revenants, Murphy’s characters seem fuelled by this sort of indomitable spirit. He’s as much a product of his homeland as he is a proud emblem of it.

What a beautiful interview. I wish Cillian knew just how much love he has from his loyal fans, myself included. I adore him as a man and an actor which he was clearly born to do. I know it’s all make believe to him but for us it’s different in that he becomes the character he plays, like he morphs into them. He is ridiculously handsome with that jawline and those cornflower eyes that are like no others in the universe. When he speaks you just hang on every word because his voice is like velvet. I love him for all those reasons but what’s is so special about him is that he has a life separate from all his acting and he is so humbled by it all and that makes him even more amazing. I adore and love him so much and have been his loyal fan since I first saw him in Disco Pigs. So cheers Cillian with love from the U.S.

I second that emotion.

I dated a man once not dissimilar to the Shelby character he looked very much like Cillian. Need I say more. The strength of his acting particularly in this role increases ones ability to touch an inner soul in many of us is uniquety of the highest quality. Long may he reign on our screens for the sheer unadulterated pleasure of his presence and indeed to make us all feel alive again.

At home with Cillian Murphy. A dream 🙂

Lovely balanced and interesting article – thank you.

This seems kind of strange/ inappropriate here, but I need to thank Cillian Murphy. I’ve had a very difficult decade, full of trauma bringing up two autistic children – I had to put everything of me on hold to get through. I was a musician, and like him I researched every piece I taught or played – the art, the literature, the music. I then developed my own health problems – losing the use of my fingers, hands, arms, shoulders; a cruel form of grief for a musician to endure. And so, in the last decade I have lived without music and the other arts. Music, in particular became very painful emotionally to engage with, I even found it difficult to listen to an entire piece of music. Anyway, I started listening to CM’s radio 6 show – and his genuine enthusiasm for music and literature spoke to me and I gradually let a little music back into my life. I have since continued to explore old and new music, and it is thrilling and connecting and life-affirming.

This is one EPIC example of a public overshare (!) but if someone, somewhere can pass on this message of thanks – that I am and will always be deeply grateful to him – I would appreciate that.

I owe him a drink.

I can relate….all of you said it and said it well, honest and raw, there is no shame in adoring Cillian, it’s almost impossible not to I think, for all the above reasons…Looking forward to what the future has in store for Cillian in regards to film and theatre, and maybe musically as well. Cheers

I love “Peaky Blinders” and watching Cillian Murphy’s acting performance, but I really, really love his guest stints on BBC Radio 6 Music. As he might say, “They’re pure class.”

I think he is a fantastic actor. He can summon up deep emotions and can transform himself into such a variety of personalities. I am not a big fan of celebrity worship and neither are the celebrities, but I do admire his down to Earth attitude and his support of causes, I can get behind that! Seems like a great guy, his Parents must be amazing people.