Were they heroes or traitors? The San Patricios Battalion or El Batallón de los San Patricios were Irishmen who fought against America during the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848.

Beginnings

It started with the Irish famine of the mid-19th century. In October 1845, a blight devastated Ireland’s potatoes, ruining about three-quarters of the crop. The blight returned in 1846 and around 350,000 people died of starvation. An outbreak of typhus also ravaged the population, leading massive numbers of Irish to immigrate to America.

In 1846, thousands of these immigrants enlisted in the U.S. Army, joining the forces under General Zachary Taylor that invaded Mexico after Congress declared war on May 13 that year. In all, 4,811 Irish-born soldiers served in the U.S. Army during the Mexican-American conflict.

Among those already serving in the U.S. Army, was twenty-eight-year-old Irish émigré John O’Reilly from Clifden, Galway. O’Reilly had previously served in the British Army, where he acquired a deep knowledge of artillery, but he left in 1843 for the United States.

On September 4, 1845, O’Reilly enlisted for five years in the 5th U.S. Infantry Regiment at Fort Holmes in Mackinac in Michigan and was sent to Corpus Christi in Texas to join Taylor’s troops. But, before the U.S. had even declared war, O’Reilly had organized a company of foreign soldiers at Matamoros to fight the invading U.S. forces. The St. Patrick’s Battalion, known to the Mexicans as the “San Patricios,” would eventually number several hundred men. While O’Reilly left no memoirs and so one can only speculate on why he deserted, he was doubtless influenced by the harsh treatment meted out to Irish immigrant soldiers, including harsh discipline, the overt racism of the Protestant officers, and being forbidden to attend Sunday Mass. Later, while being held prisoner in Mexico City, O’Reilly wrote to a friend in Michigan: “Be not deceived by a nation that is at war with Mexico, for a friendlier and more hospitable people than the Mexicans there exists not on the face of the earth.”

On September 4, 1845, O’Reilly enlisted for five years in the 5th U.S. Infantry Regiment at Fort Holmes in Mackinac in Michigan and was sent to Corpus Christi in Texas to join Taylor’s troops. But, before the U.S. had even declared war, O’Reilly had organized a company of foreign soldiers at Matamoros to fight the invading U.S. forces. The St. Patrick’s Battalion, known to the Mexicans as the “San Patricios,” would eventually number several hundred men. While O’Reilly left no memoirs and so one can only speculate on why he deserted, he was doubtless influenced by the harsh treatment meted out to Irish immigrant soldiers, including harsh discipline, the overt racism of the Protestant officers, and being forbidden to attend Sunday Mass. Later, while being held prisoner in Mexico City, O’Reilly wrote to a friend in Michigan: “Be not deceived by a nation that is at war with Mexico, for a friendlier and more hospitable people than the Mexicans there exists not on the face of the earth.”

The War Begins

Not all the San Patricios were deserters from the U.S. Army, as their number also included Irish and other Europeans already settled in Mexico. When the Mexican generals learned of the difficult conditions the Irish faced in the U.S. Army, they encouraged defections by promising deserters land, money and promotions, surreptitiously distributing leaflets exhorting Irish Catholics to join them.

The conflict was not universally popular in the United States. Henry David Thoreau went to jail rather than pay taxes to support it and newly elected House of Representatives member Abraham Lincoln denounced the war in Congress. Former president John Quincy Adams opposed it and future president Ulysses S. Grant described the conflict as “the most unjust war ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.”

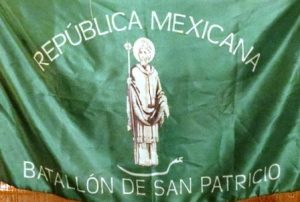

In May 1846, O’Reilly and several dozen men under his command first skirmished with the Americans at the siege of Fort Texas. Four months later, on September 21, 1846, the San Patricios first fought as a formal Mexican army unit, providing artillery support and adding to their reputation in handling heavy weaponry. The San Patricios’ green battle flag displayed an Irish harp surrounded by the Mexican coat-of-arms with a scroll reading “Freedom for the Mexican Republic,” and the Gaelic motto “Erin go Brágh” (“Ireland forever”).

At the battle of Monterrey, September 21-25, 1846, the San Patricios fought with valour.

On February 23, 1847, Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna attacked the dug- in U.S. forces at the Battle of Buena Vista, also known as the battle of Angostura. The San Patricios again played a prominent role. During the battle, two six-powder cannon belonging to the U.S. Fourth Artillery were captured by Mexican forces due to the intense fire from the San Patricio artillerymen. Several San Patricios, including Juan O’Reilly, who was subsequently promoted to the rank of El Capitan, received the Cruz de Honor de la Angostura for bravery.

On February 23, 1847, Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna attacked the dug- in U.S. forces at the Battle of Buena Vista, also known as the battle of Angostura. The San Patricios again played a prominent role. During the battle, two six-powder cannon belonging to the U.S. Fourth Artillery were captured by Mexican forces due to the intense fire from the San Patricio artillerymen. Several San Patricios, including Juan O’Reilly, who was subsequently promoted to the rank of El Capitan, received the Cruz de Honor de la Angostura for bravery.

In June 1847, the San Patricios were transferred from the artillery branch to the infantry and merged into the Foreign Legion branch of the Mexican Army, becoming known as the First and Second Militia Infantry Companies of San Patricio.

Later, the battlefront shifted to eastern Mexico and when General Winfield Scott landed his troops and captured Veracruz on March 28, 1848, the U.S. soldiers marched on Mexico City.

The Battle of Churubusco

The San Patricios’ last stand was in defense of Mexico City at Churubusco on August 20, 1851, one of the bloodiest battles of the war. Mexican President Santa Ana said, “With a few hundred more men like the San Patricios, Mexico would have won the battle.” Sixty percent of the San Patricios were killed or captured, fighting until their ammunition ran out. Three times a white flag of surrender went up, to be torn down by the San Patricios, who knew what fate awaited them if captured by the U.S. Army. Only the intervention of a U.S. Army officer stopped the battered victors from killing the captured San Patricios, who included the wounded O’Reilly.

Retribution

Retribution

U.S. military justice was brutal. Of the 83 San Patricios captured, O’Reilly and 71 San Patricios were court-martialed. Fifty of the San Patricios were sentenced to be hanged and 16 were flogged and branded. To the surprise of the U.S. Army, Scott reduced O’Reilly’s sentence from hanging to “whipping and branding,” justifying his action by noting that because O’Reilly had deserted prior to the outbreak of hostilities, the Articles of War dictated that he could receive only the lesser sentence. O’Reilly and his cohorts were also branded on their cheeks with a two-inch-high letter “D” for deserter.

On September 13, on a hill outside Mixcoac in sight of Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle, U.S. Army Colonel William S. Harney – a harsh disciplinarian – brought thirty condemned San Patricios to a gallows within view of the battle still raging around the fortress-castle. The men were executed “in a fearful dance of death,” according to an eyewitness. In an incident of brutal irony, Harney himself was an Irishman. O’Reilly and his flogged companions were forced to dig their fallen comrades’ graves. Mexicans were shocked and outraged by the brutal treatment of the San Patricios.

On September 14, the American Army entered Mexico City, effectively ending the war. By the subsequent Treaty of Guadeloupe Hildago, Mexico lost approximately half its territory, for which it received $15 million in compensation. The San Patricios who had not been hanged were imprisoned for the duration of the war.

Aftermath

The Mexican-American War had the highest desertion rate in U.S. military history, with over 5,280 of the nearly 40,000 U.S. Army regulars who saw duty disappearing. Of that figure, nearly 1,000 were Irishmen. For the U.S. Army, the conflict provided a training-ground for the men who would lead the Northern and Southern armies in the upcoming American Civil War. General Taylor used his fame as a war hero to win the Presidency in 1848.

O’Reilly returned to the Mexican Army and was promoted to colonel. Later, he was arrested on suspicion of taking part in an abortive revolt against the Mexican government and rumors of his execution by a firing squad nearly sparked a revolt by the reorganized St. Patrick’s Battalion. According to some accounts, O’Reilly died in Veracruz in August 1850 and is buried there.

The San Patricios have been honoured in Mexico as foreign heroes. In 1959, the Mexican government dedicated a commemorative plaque to them in the Mexico City suburb of San Angel, which lists the names of all members of the battalion who lost their lives fighting for Mexico, either in battle or by execution.

In September 1997, on the 150th anniversary of the U.S.-Mexican war, legislation was passed to inscribe upon the Wall of Honor inside the Mexican Congress, “Defensores de la Patria 1846-1848” and “Batallón San Patricio.” In April 1999, Irish President Mary McAleese made a state visit to Mexico and laid a wreath at a monument in Mexico City to the San Patricios. The Irish fighters are also commemorated in Mexico each year on St. Patrick’s Day and on September 12, the anniversary of the first executions.

In September 1997, on the 150th anniversary of the U.S.-Mexican war, legislation was passed to inscribe upon the Wall of Honor inside the Mexican Congress, “Defensores de la Patria 1846-1848” and “Batallón San Patricio.” In April 1999, Irish President Mary McAleese made a state visit to Mexico and laid a wreath at a monument in Mexico City to the San Patricios. The Irish fighters are also commemorated in Mexico each year on St. Patrick’s Day and on September 12, the anniversary of the first executions.

In the U.S., recognition of the San Patricios has been muted. In 1999, Hollywood released a film based on them called One Man’s Hero, starring Tom Berenger. In 2010, American musicologist Ry Cooder, in collaboration with renowned Irish band the Chieftains, released their San Patricios CD.

Hi, great article on the Saint Patrick’s:) I thought you guys might be interested in my blog on them https://secretireland.ie/why-did-the-saint-patricks-battalion-change-sides-and-fight-for-mexico/ and https://contentwriterireland.ie/

glad to hear it. I am writing a book on the Mexican War and would like to include this event

Who knew better than the Irish what injustice was and they clearly took the opportunity to fight against it as the San Patricios. Anti Irish racism was rife amongst the Anglo settlers in America at that time and that was further encouragement to fight for justice for Mexico.