66 Days

Hardly eight years have passed since Steven McQueen gave the world in his film, Hunger, an inescapable depiction of one of the core plot points of the Northern Irish struggle: the decision by incarcerated Republicans to fast unto death, if necessary, in Long Kesh Prison. As galling as a portrait of such an act is, there nevertheless persists a restless curiosity to understand the motives and the drive behind it. With Brendan Byrne’s recently released film, Bobby Sands: 66 Days, we now have a feature documentary that forms an intriguing companion to McQueen’s drama.

Hardly eight years have passed since Steven McQueen gave the world in his film, Hunger, an inescapable depiction of one of the core plot points of the Northern Irish struggle: the decision by incarcerated Republicans to fast unto death, if necessary, in Long Kesh Prison. As galling as a portrait of such an act is, there nevertheless persists a restless curiosity to understand the motives and the drive behind it. With Brendan Byrne’s recently released film, Bobby Sands: 66 Days, we now have a feature documentary that forms an intriguing companion to McQueen’s drama.

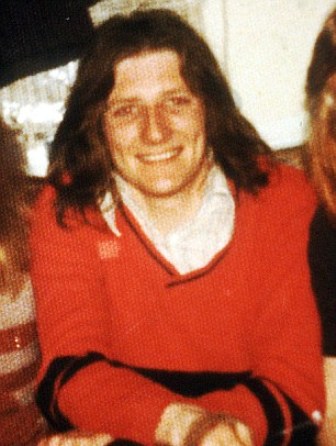

The film benefits hugely from the BBC’s wealth of archive. Much of the archive used will be unfamiliar to even the most inveterate documentary viewer; its vividness and pervasiveness in this documentary helps to compensate for the fact that Sands was a relatively unknown figure when he entered Long Kesh—very little archive of Sands himself is extant.

Visually, this documentary is at times wondrous: presented almost from beginning to end with a grainy, filmic finish; the mixture of animation with photography and archive is superbly well achieved. Solid media research complements the beautiful images: that the British and US media covered Sands’ protest so extensively is unsurprising, but it was news to me that, for example, Russian newspapers gave such coverage to Sands’ protest and death.

The rostrum of participants is unconventional. Granted, a slew of Sinn Féin and IRA comrades appear as do a predictable retinue of writers and journalists. But the presence of so many American contributors is quite surprising, given that they had only the most tangential connection (or none) to Sands’ Hunger Strike. They are a fresh alternative to a tiresome reaching for phony “balance” and “on the other hand-ism” in documentaries. Journalist Fintan O’Toole is so extensive in this documentary that one is tempted to describe him as its protagonist. While O’Toole had a role as analyst in the Hunger Strikes period, his inclusion as the front man was a peculiar decision but an occasionally invigorating one.

Not everything works so well. In textual side-glances we are told rather self-evident factoids like Ireland was for a long time governed by Britain. As a history lesson is that not rather feeble? Also, Father Seán McManus’ acerbic tones are countervailed by Irish Ambassador Seán Donlon—two people whose missions in Washington DC during the Hunger Strikes were in direct opposition to each other. But the pressure exerted on US Congressmen who represented heavily Irish constituencies is unexplored, despite the fact that the politicization of the grassroots in the US was a big consequence of the Hunger Strikes.

As is evident from Sands’ Prison Diary and his poem, “The Rhythm Of Time”, Sands embodied diehard resilience. We learn early in this documentary that that resilience sprang in part from the will of his parents to encourage violent resistance against the occupying British Army’s barbaric harassment of Belfast Catholics at the outbreak of the Troubles. Scenes here of the Strikers’ families, principally their sisters and mothers, is harrowing.Yet in searing footage filmed in the closing days of his life, Sands’ mother made the simple plea that her son’s death should not beget more violence.

Byrne and his collaborator Trevor Birney have in the past made films (witness The Docklands Bomb: Executing Peace) using the device of a countdown. This device, applied to the case of Sands, is problematic: his fate is so widely known that surely placing a greater emphasis on his legacy would be more intriguing? In a historical documentary made thirty-five years after the Strikes, why was a more rigorous investigation of the consequences of the Hunger Strikes not undertaken? True, there is scant support today for diehardism but the fact remains that the ultimate political objective of the Hunger Strikers, a United Ireland, was not achieved, and that fact is the great unmentioned here.

Sands’ election in absentia to Westminster Parliament during his hunger strike was a coup for, and a central milestone in, the rise of Sinn Féin. But a little less party politics and more deeper political enquiry would have been welcome. Sands and his cohorts’ extraordinary courage in facing death signified an absolute determination to achieve rights. The Strikers demanded political status rights in prison and their right to assert a United Ireland of all the people on the island of Ireland. Sands and the other nine Strikers who fasted onto death had a clear goal, and the IRA leadership settled for less. Yeats’ famous lines from ‘Easter 1916’, “was it needless death after all?” come to mind in recalling their sacrifice.

At the same time as the Hunger Strikes a newly formed theatre company based in Derry, Field Day, headed by Brian Friel and Stephen Rea, determined that they would insert themselves into the political crisis in the North of Ireland. Tellingly, they produced a version of Sophocles’ timeless masterpiece, Antigone, partly in response to the scenes of Long Kesh—its walls pasted with excrement, its naked and starving protestors’ descent into hell found in an Ancient Greek play an almost perfect parallel. The point being: Irish-speaking, poetry-writing, story-telling, history-reading prisoners created a climate of self-examination and enlightenment, and it was that mindset that enabled an end to the vicious conflict in Northern Ireland. The Hunger Strikes, like so much else that occurred in the North, seems now to have been a process towards that central discovery. But was it needless death after all?

Maurice Fitzpatrick, September 2016