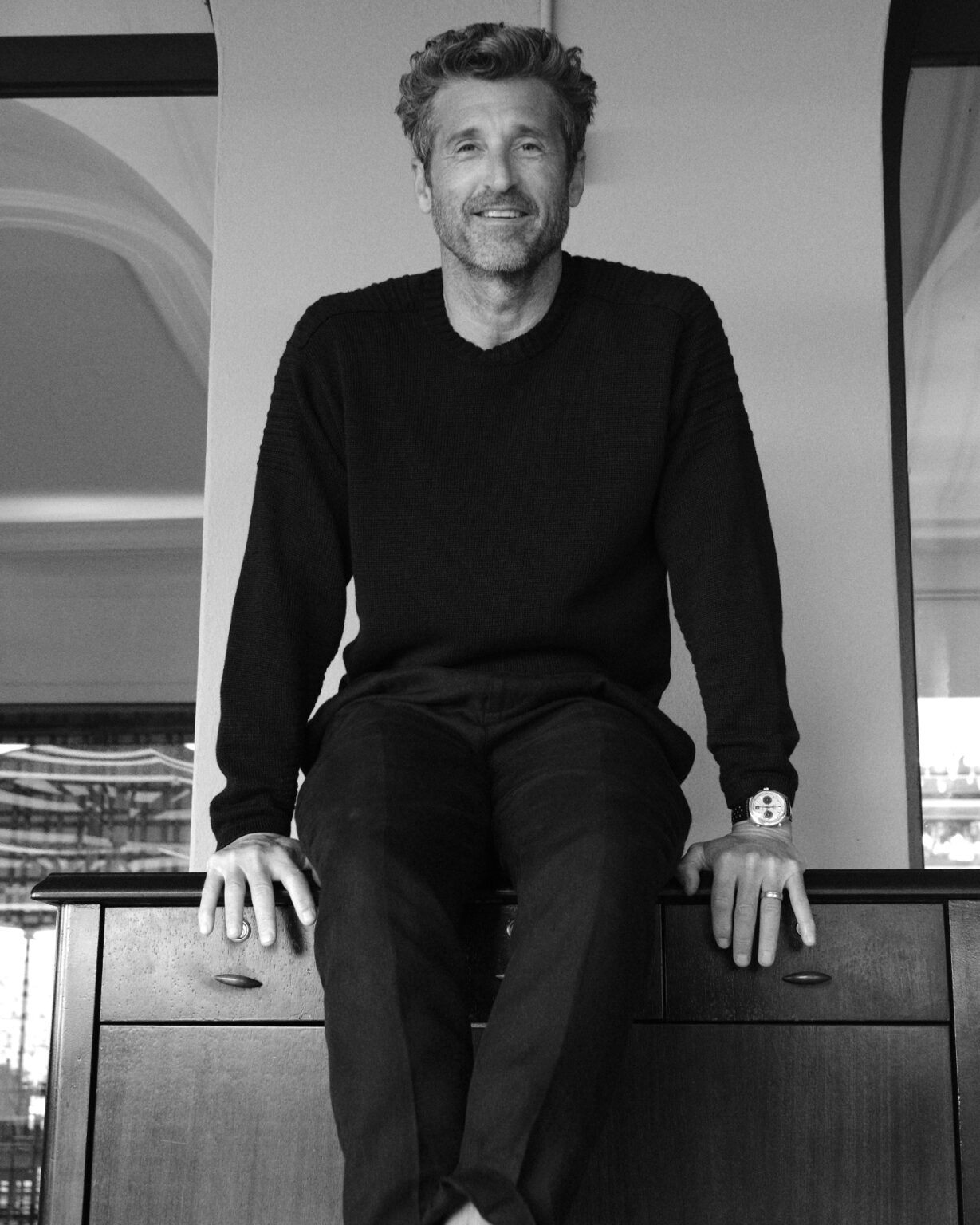

Patrick Dempsey has put in his seat time — to use a racing he seasoning a driver gets with each hour spent behind the wheel. The 57-year-old multi-hyphenate actor, producer, team owner, and driver with more than 35 years of experience in the entertainment industry (from playing lovestruck young men in Can’t Buy Me Love and Happy Together to the most handsome doctor on television in Grey’s Anatomy, and the romantic lead in Enchanted), is now widely recognized in motorsports as an accomplished competitive racing driver and owner of Dempsey Racing. Those divergent career laps converge in Dempsey’s latest project, Michael Mann’s Ferrari where he plays Ferrari driver Piero Taruffi, the winner of the fabled and tragic 1957 Mille Miglia race that becomes the dramatic centrepiece of the film.

“It’s not any one person who makes a movie. It’s a collaborative effort. It’s like a sports club. You need teamwork and you need support.”

Dempsey first read the script more than a decade ago and knew he had be a part of it, keeping tabs on its development ever since. And better than most actors, he knows what it takes to play an endurance racer, as he actually is one.

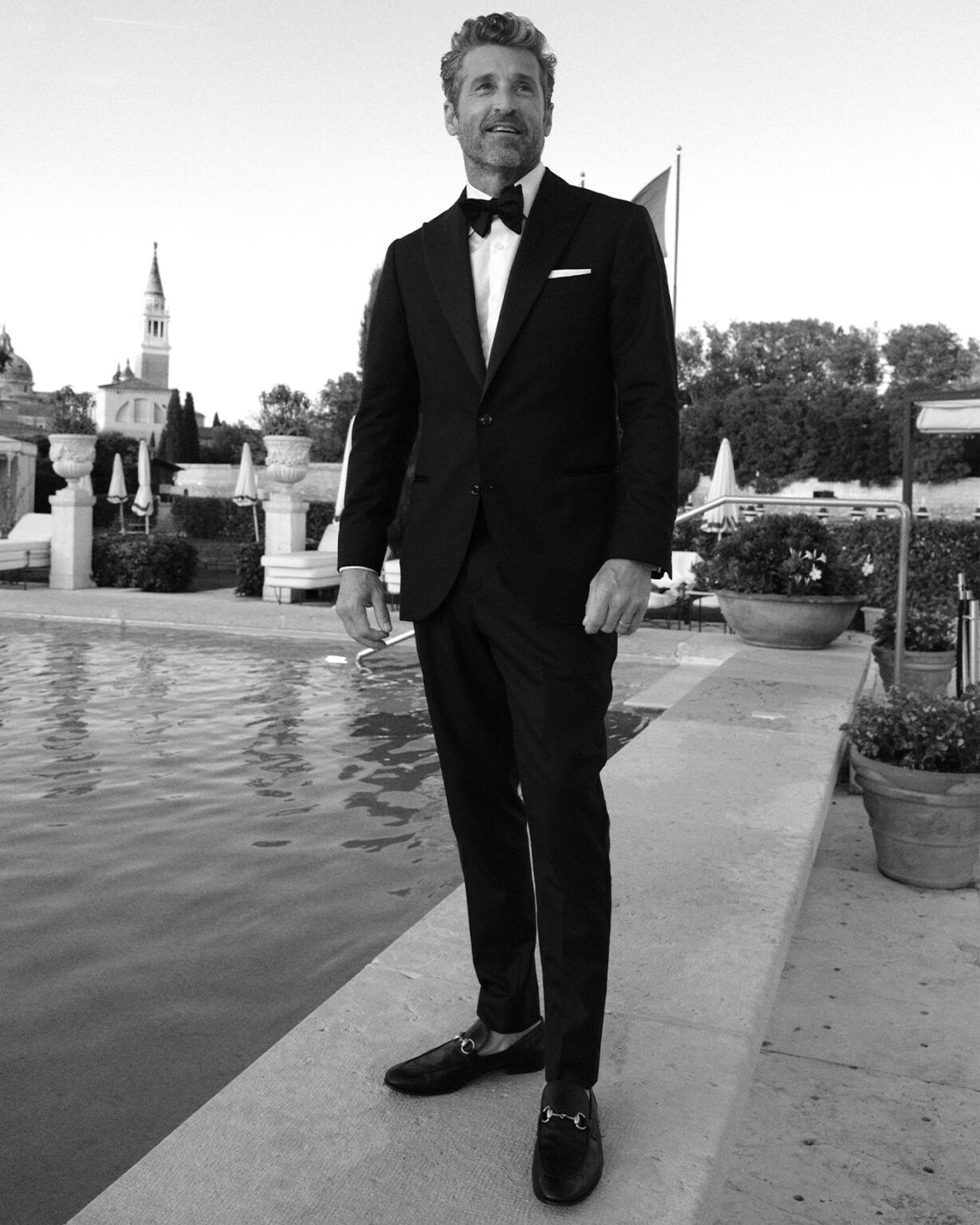

Dempsey spoke with us shortly after the Venice Film Festival, where Ferrari became the first high profile production to land a star-studded red carpet since the SAG-AFTRA strike began on July 14, thanks to an interim agreement between the guild and independent production companies such as Neon, who are not members of the AMPTP. The contract, as star Adam Driver explained at the press conference following the premiere, affirms that Neon has agreed to the terms of the guild’s current proposal.

Dempsey strikes a diplomatic tone about the whole business, especially when asked if agreements like this one might help break through the stalemate. “We have to realize,” he says, “that it’s not any one person who makes a movie. It’s a collaborative effort. It’s like a sports club. You need teamwork and you need support. And I think these are the issues we need to find common ground [and] to move forward and remove the ego, because people are really hurting.” A working performer who used to live paycheque to paycheque before superstardom, Dempsey is most concerned for those who are still in the early years of their careers: “people who are just beginning, or the industries that are supporting the film industries: they’ve already had a hard time with COVID, and now it’s just absolutely devastating.”

As anxious as he is about the state of the industry, Dempsey is ecstatic about the launch of the film, a labour of love for both him and Mann — you can find photos of them together at racing events as far back as 2011 — finally brought to fruition. That delight comes through in his voice when he talks about being sold from the moment he read the script, which follows beleaguered ex-racer and company owner Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver) in the summer of 1957, as the threat of bankruptcy collides with his domestic strife and the recent loss of his son on the verge of the Mille Miglia, a thousand-mile race across Italy.

Beyond Mann’s gift at dramatizing Ferrari at several professional and personal crossroads, Dempsey was struck by the opportunity to help recreate this golden age of racing. “I found this period in motorsports history from the fifties through the early sixties the most romantic, and certainly the most deadly period,” he says. Dempsey credits Mann’s meticulous research and knowledge of the period for making this history feel contemporary. “We had all of these incredible vintage cars, many of which had the pedigree of having raced that particular year, with hundreds of extras dressed up in period costumes. It was like stepping back in time.” For Dempsey, bringing that period alive included driving a recreation of Taruffi’s car, down to the period-accurate absence of a roll cage. “You feel the danger. It was real. It was palpable. You appreciated their ability all the more by having that experience.”

“They’re incredibly competitive on the track, but when the race is over, there’s this fellowship and camaraderie. There’s just so much respect.”

Dempsey has his own history with the storied Italian manufacturer, having raced a Ferrari F430 GT at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 2009. “I certainly understood the importance of the brand,” he says, “not only within Italy, but representing them on a track and in an iconic race like Le Mans. As a team owner, I understood the culture and the dynamics within the company — the passion and commitment. So that was all ingrained and was one more layer that went into performing. I respected the tradition. I was humbled by being a part of the history.” As an aficionado as well as a driver, the film was a dream opportunity to delve into the immaculately-kept Ferrari archives, which were opened up to Dempsey by the manufacturer, he feels, in part because of his racing experience. “We had an opportunity to go into their museum and get all of the notes from the engineers, so you could understand better what they were dealing with during the race, what was working, what the mechanical weakness was, and give you perspective.”

“You’ve gone into battle together and the stakes are incredibly high. And when you come out, there’s just this deep connection with your fellow competitor and fellow teams.”

That he got the green light to play the Ferrari driver at all, given his longtime partnership with Porsche, is a testament, Dempsey says, to the good sportsmanship of racing. “These are family-owned companies,” he points out. “They’re incredibly competitive on the track, but when the race is over, there’s this fellowship and camaraderie. There’s just so much respect.”

That cross-company gentleman’s agreement, he thinks, comes from the rare knowledge of what it takes to engineer a winning car, which transcends the more mundane rivalries of the business. “You want to beat them when you’re on the track, don’t get me wrong,” he laughs, “but when you’re off the track there’s a celebration. You’ve gone into battle together and the stakes are incredibly high. And when you come out, there’s just this deep connection with your fellow competitor and fellow teams.”

Taruffi is a biopic-worthy character in his own right; a statesman for the sport who became a safety advocate following the deadly race depicted in the film. “I don’t think he ever really got the attention he deserved because he survived,” Dempsey says, referencing the accidental death in the race of Taruffi’s Ferrari teammate, the high society playboy Alfonso de Portago, who lost control and crashed when his front tire exploded, killing himself, his navigator, and several spectators. The haunted nature of the event, Dempsey feels, overshadowed Taruffi’s impressively diverse portfolio. “He did a lot of endurance racing. He was with Ferrari very early on, since the twenties. He had won motorcycle championships. He was a polymath. He was an incredible engineer. He understood aerodynamics. He was a teacher, and he was a survivor of an era that was incredibly deadly.”

As for whether it’s a unique challenge to play a historical driver, given the uncanniness of getting into cars from more than sixty years ago, Dempsey demurs that the real obstacle was not getting into Taruffi’s head but his hair. “It was easy because it was just the reality of doing,” Dempsey says of coming to know Taruffi’s driving style. Less easy was getting Taruffi’s silver fox hair styling just right, keeping it safe from the wear and tear of his helmet and making it look believable so that he could, as he puts it, “disappear from the outside in.” “The hardest part was my hair got fried because we had to dye it so much,” he jokes.

“Whether you’re a person who makes shoes or you’re a person who builds furniture or you’re a carpenter, you are a craftsperson: you take pride in your work. It gives you your identity.”

But getting it right is important to Mann, a perfectionist who makes movies about other perfectionists. There’s a lot of the Ferrari founder in Mann and a lot of Mann in his characterization of Ferrari, Dempsey observes, marvelling at the director’s level of preparation and attention to detail. “He records every conversation. And then what he does is have it typed out, so he has a record of it and he can go back to it. He works with these copious notes. He’s relentless when he wants something.”

Demanding as the filmmaker is, Dempsey says that Mann is also the first to celebrate his collaborators when they get something right. It’s not lost on Dempsey that Mann makes films about men who define themselves by what they do and that as an actual racing driver he lends a unique authenticity to the film. He balks at the suggestion that this authenticity is exclusive to his dual experience as both driver and actor, though.

“Whether you’re a person who makes shoes or you’re a person who builds furniture or you’re a carpenter,” he says, “you are a craftsperson: you take pride in your work. It gives you your identity. I think that applies to filmmaking.”

Ferrari is coming out amidst a renaissance for motorsports, which Dempsey credits in part to the success of Netflix’s documentary series Formula 1: Drive to Survive. He is both heartened and bemused by the public’s rekindled romance with racing. “I always have a twinkle in my eye,” he says with a hint of mischief, when fans of the show tell him it’s inspired them to start racing. “I say, okay, good luck to you.”

For Dempsey, moving from a childhood love of cars — instilled by watching the Indy 500 with his father — and a competitive background in skiing to a career in racing was largely an education in an unforgiving business. “I bought a race team that was going bankrupt and that should have warned me going into the whole thing that it was a money pit,” he says when I ask what he knows about racing that he didn’t when his wife first gifted him a three-day competition certificate to Skip Barber Racing School. “I had to work very hard and I had to do a lot of self-funding. And thank God I was on a very successful show that allowed me to do that.”

“You go into a different consciousness, and then when you have those moments when everything is working — and they’re few and far between — it is magical. And that’s where you want to be able to live.”

“You go into a different consciousness, and then when you have those moments when everything is working — and they’re few and far between — it is magical. And that’s where you want to be able to live.”

Like any tough sport, racing has become more viable and more rewarding, Dempsey notes, as he’s put in the seat time while building for rewarding sponsorships. He credits his professional affiliations with Porsche and TAG Heuer for not only helping him navigate the treacherous financial curves of motorsports but teaching him about “creating the right culture and the right atmosphere” within a team.

As for whether racing is a purer experience than acting, despite the overlapping business machinations of the two industries, Dempsey is circumspect. It’s true, he says, that the potential to be hurt in racing creates an urgency that’s less present in filmmaking, but he maintains that there’s a similarity between the transcendent quality of racing and being in front of the camera when one is in the moment. “There is a spirituality to it that transcends everyday life,” he says of both professions, noting that in acting it’s about listening and responding and blocking everything else out, while in driving, “you want to be so connected to your car that it’s an extension of your thought; that it becomes instinctual.”

He sounds, I tell him, like a Michael Mann character — particularly Al Pacino’s lawman Vincent Hanna in Heat, who tells his long-suffering wife that he needs to hold onto his angst because it keeps him “sharp, on the edge, where I gotta be.” “It’s being present,” Dempsey says simply. “You go into a different consciousness, and then when you have those moments when everything is working — and they’re few and far between — it is magical. And that’s where you want to be able to live.”

Story by Angelo Muredda / Source: sharpmagazine.com

Leave a Comment