Aberdeenshire and Beyond

Nearly twenty years ago I had the good fortune of being writer in residence at the Aberdeen International School – a posh, well-appointed facility near Aberdeen for kids from all over the world. Aside from my pleasant, daily duties of talking with students about creativity and writing, I had enough leisure time to hike along a local canal path, go bike-riding through the back roads, and generally ramble around the most agreeable countryside my shoe leather had ever encountered.

Nearly twenty years ago I had the good fortune of being writer in residence at the Aberdeen International School – a posh, well-appointed facility near Aberdeen for kids from all over the world. Aside from my pleasant, daily duties of talking with students about creativity and writing, I had enough leisure time to hike along a local canal path, go bike-riding through the back roads, and generally ramble around the most agreeable countryside my shoe leather had ever encountered.

My teacher-host, fellow Nova Scotian Andy Field, even took me surfing. At first, we ventured just south of Aberdeen, where the water was surprisingly warm (as it turned out, the sewage plant emptied into the ocean thereabouts.) Later, we sported wetsuits on a pebbly beach right in downtown Stonehaven, dropping in on small North Sea waves before the backdrop of a bustling village that dates back centuries. Fortified with a couple of pints of Guinness, we even stole onto one of Scotland’s famous public golf courses just as the sun dipped. Luckily, I was able to blame my poor performance of the “gentleman’s game” on the diminishing light.

When my residency ended, I promised myself that I would return to explore this northeast corner of Scotland, with its sumptuous land and historical riches. Thus, my wife Linda and I recently enjoyed a few adventures in that part of the world, renting a small stone cottage in the tiny village of Pitmedden. It was a converted one-room schoolhouse really, made of solid blocks of granite, and conveniently located in the front yard of a newer house owned by a professional self-help guru who drove the shiniest BMW that I had ever seen.

We seek connections in this world, wherever we go, and there was another thread that brought us here, albeit a sad one; a friend of nearly thirty years, Jim Lotz, had recently passed away from pancreatic cancer. Jim was a brilliant independent thinker, an activist and author, and a feisty, good-natured Brit who had immigrated to Canada to roam the arctic, fight for social justice, and dole-out advice to younger writers like me: “Don’t ever listen to the bastards who say you can’t do it. Just get on with it and bugger all.”

I had helped edit Jim’s autobiography, Sharing the Journey, and the book had been at the printer as he lay dying. He had grown up in Liverpool, and watched as his neighbourhood was bombed by the Nazis before he was shipped off to the safer environs of Aberdeenshire, near the town of Oldmeldrum. Of the Scottish countryside, he had this to say:

“This hard, barren land touched some deep, responsive chord in my nature. I enjoyed roaming through glens and over moors, happy in my own company, delighting in the scenery and the romantic history of the Highlands, while coping with atrocious weather.”

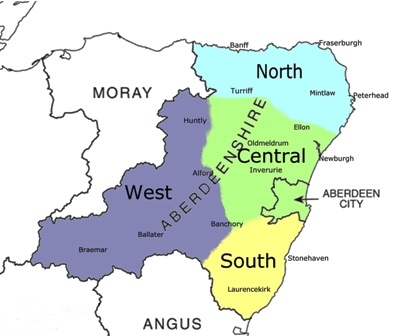

Our own explorations of the area actually took us farther afield from Aberdeen and into a broader expanse of coast and mountains sometimes labelled the Grampian region, although this appears to be a label of political jurisdiction slapped onto this part of northeast Scotland sometime between 1975 and 1996. The name comes from the bold and somewhat bald mountains of the region (8,700 square kilometres of them), and – as Jim Lotz pointed out – it is one lovely and evocative piece of geography.

I dutifully delivered a copy of Jim’s book to a state-of-the-art library outside of Oldmeldrum, though the librarian didn’t quite know what to make of it (or me.) If anyone is out and about there, however, do me a solid and check to see that it is at least catalogued and on the shelves.

As the name implies, Oldmeldrum really is quite old. The Meldrum family built a castle here around 1236. The third Earl of Buchan reportedly found shelter for his soldiers here around Christmas of 1307, before being defeated by Robert the Bruce in a nearby battle not long after that.

In Oldmeldrum, I dutifully sampled the wares at the famous Garioch Distillery, but declined to purchase the more expensive vintage whiskeys with price tags in the range of $400 – $500 US. Linda and I did find refreshment at a downtown pub with a nautical theme. It was a wonderfully cramped and convivial establishment in one of the many grey stone buildings of the town.

In Oldmeldrum, I dutifully sampled the wares at the famous Garioch Distillery, but declined to purchase the more expensive vintage whiskeys with price tags in the range of $400 – $500 US. Linda and I did find refreshment at a downtown pub with a nautical theme. It was a wonderfully cramped and convivial establishment in one of the many grey stone buildings of the town.

Our favourite pub, however, was the more contemporary BrewDog brewery in Ellon to the east. This is one of Scotland’s new breed of craft brewers, whose motto appears to be “Equity for Punks.” No one was quite able to explain to us what that meant, but they had a great line of hoppy beers and good hospitality. The business was founded way back in 2007 by two guys named James and Martin. James had this to say about the origins: “Martin and I were bored of the industrially brewed lagers and stuffy ales that dominated the U.K. Beer Market.” And, as they say, the rest was history. In actuality, what – on the surface – appeared to be an indie-business run by some highly creative counter-cultural young brewmeisters was actually on its way to becoming a very lucrative multinational corporation.

Like James and Martin, I too was weary of stuffy ales, and BrewDog’s Punk IPA (my personal favourite) was proving to the quaffing masses that the new brew in town was taking over.

Hiking mountains and getting wet in salt water are always on our agenda if possible when we travel. We found our first waves for boogie-boarding in the waters of Fraserburgh Bay to the north, well insulated by wetsuits of course. It was a sandy haven of hikers, surfers and kite-surfers, where everyone was friendly and kind. If you are in that neck of the woods, the dunes alone are worth the excursion.

Fraserburgh itself is a major bustling fishing port. We had read reports of heavy drug use among young bored fishermen who would return from the sea with money in their pockets and a craving to get dangerously high, but alas we found nothing but good vibes among the locals, both young and old. In town, we discovered a house known as Maggie’s Hoosie, a traditional fishing cottage preserved for tourists. The spinster Maggie Duthie lived there until she died in 1950 with an earthen floor, no heat or electricity, and a lifestyle not unlike that lived by her ancestors two hundred years ago.

With a good map you can find curiously named towns in this part of Scotland that are almost always worth a visit.

In particular, I was curious about a place called Udny Green, which turned out to have a beautiful town commons and an upscale restaurant named Eat on the Green. After much deliberation, the maitre’d took pity on us and gave us a small corner table if we promised not to stay longer than an hour. On the wall were photos of the Queen, Pierce Brosnan and Sean Connery. It was that kind of place. We polished off the pricey meal and headed off to check out Pettymuick, Tillygreig, Whiterashes, Port Elphinstone, Balhalgardy and Inverurie. Then, while taking a break in Burnhervie, I spied – on a map – a symbol for a nearby ancient monument called The Maiden Stone.

The Maiden Stone was a bit hard to find – located in a field with no fanfare, south of Pitcaple, off a back road, and west of a town called Chapel of Garioch. The road itself was one of those interesting rural avenues; a single lane about the width of a sidewalk, but most perfectly paved – as if designed for elves driving miniature automobiles.

The Maiden Stone was a bit hard to find – located in a field with no fanfare, south of Pitcaple, off a back road, and west of a town called Chapel of Garioch. The road itself was one of those interesting rural avenues; a single lane about the width of a sidewalk, but most perfectly paved – as if designed for elves driving miniature automobiles.

Since there was no one else on the road but us, our tires straddled the path as we made several wrong turns until we found the sought-after Maiden Stone. When approaching the stone, we met a rather excited English tourist who was snapping photographs from every possible angle. Happy to see us, and eager to share his enthusiasm for what appeared to be an upright lichen-covered pink granite rock with a notch cut out of it, he told us that it dated back to the 8th century when the Picts lived hereabouts. According to legend, the daughter of a laird made some crazy bet with a man who turned out to be the devil. The impetuous young lass, on her wedding day no less, bet the stranger that she could finish her baking task quicker than he could build a road to the top of a local mountain. If he lost, then she would marry him instead of her betrothed. I queried the informative Englishman why someone would make such a bet, especially on her wedding day, but he had no clear explanation, and seemed miffed that I would even ask.

At any rate, the devil being the devil, built that mountain road in jiffy and came to claim his young bride. The laird’s daughter made a run for it and swore she’d rather turn to stone before marrying the likes of Satan. And thus, she got her wish.

The tallest mountain we chose to climb had the curious name of Mither Tap, and we arrived just as a bus of school kids were embarking on the hike through the well-marked forest trail that led to the base of the mountain. Standing a mere 1,279 feet above sea level, Mither Tap has a commanding granite summit looking out over the other Bennachie mountains. As the trail became steeper we huffed and puffed our way to the glorious summit as giggling Scottish schoolboys kicked pebbles down on us from above. Their harried and embarrassed schoolmistress begged them to stop, shouting down apologies to us below. Despite the pelting of stones, the view from the top was well worth it on a clear day like this when you could see for miles.

Although I am occasionally of the opinion that “if you’ve seen one castle, you’ve seen them all”, Linda persuaded me that we should at least take-in Castle Fraser down around Moneymusk and Craigearn.

I drove past Castle Fraser once, pretending not to see it and thought I might get away with it, but unfortunately there was a big sign at the next crossroads pointing back to the estate. I parked, and grudgingly paid for admission. (It is probably unreasonable of me, but I feel that castles, ruins and ancient monuments should be free and open to the public, like The Maiden Stone in her grassy remote field.)

But if you are going to pick one castle in the Grampian region, Fraser is probably as good a pick as you will get. The grounds are beautiful, and it is considered one of the “most elaborate of Z-plan castles in Scotland.” Most castles have stories, and if those stories are intriguing enough then most of us don’t really care if they are true or not. At Castle Fraser, it is said that once upon a time a young princess was murdered (why, we do not know) and as she was carried down the stairs, her blood stained the steps so badly that they had to be covered over with wood. Today, I am sure, professionals with the right tools and detergents could have solved the problem – but who are we to judge?

But if you are going to pick one castle in the Grampian region, Fraser is probably as good a pick as you will get. The grounds are beautiful, and it is considered one of the “most elaborate of Z-plan castles in Scotland.” Most castles have stories, and if those stories are intriguing enough then most of us don’t really care if they are true or not. At Castle Fraser, it is said that once upon a time a young princess was murdered (why, we do not know) and as she was carried down the stairs, her blood stained the steps so badly that they had to be covered over with wood. Today, I am sure, professionals with the right tools and detergents could have solved the problem – but who are we to judge?

And, yes, it was a pretty darn good castle as far as castles go. As we walked back to the parking lot where a pair of swans from the castle pond seemed to be studying our rental car, I wondered out loud exactly how and why that murder happened – if it happened at all – and why such stories seem to linger on for centuries, while undoubtedly countless good deeds by generations of the Frasers go unremembered.

Interestingly, awhile later while falling asleep in front of the TV watching Helen Mirren in The Queen, I thought the location in the movie looked familiar, and sure enough, Castle Fraser it was.

Before heading home, I longed for one more foray to the sea and I noted a nature reserve named Forvie just north of Newburgh which would allow us another visit to the BrewDog in Ellon on our way home. On the way to Forvie, we passed what seemed to be miles of coast land that had been privatized and developed into a golf course. I wondered how the people of Scotland had allowed such pristine coastal land that had remained unbothered for centuries to be bought up and developed this way. Later I would learn that none other than Donald Trump had bought up the coastline in 2014, investing $290 million US to create the Trump International Golf Links, and in the process decimating what were once legally protected sand dunes. Suffice it to say, Mr. Trump and his links did piss off a fair portion of the population of the region.

The beach and waters at Forvie, however, were providentially protected. Linda and I hiked out to the sea along the beautiful Ythan Estuary, home of “the largest breeding colony of little terns on the east coast of Scotland.” The water was blue, the sky was cloudless. Helicopters transporting workers to and from the North Sea oil rigs did nothing to detract from the beauty and sanctity of the place. The sand felt glorious under our bare feet. The terns swooped and swirled above and, at the mouth of the estuary, we began to hear an other-worldly chorus of low moaning voices drifting towards us in the wind. As we continued to walk, the sound grew louder. Soon enough, we saw a dark, undulating mass of something on the shores across the river mouth from us.

When we reached the sea, we realized that it was a large community of seals – perhaps a hundred – lounging on the sands across from us. Their voices were loud now, drowning out everything else, and their song stirred something within me. Young seals dove from the shoreline into the clear blue water, swam and played, and then hopped back up on the sandy shoreline. That farther shore was an empty, flawless expanse of coastal wilderness, where the terns, seals, gulls and other creatures of the wind and sea would be free and safe. For a while at least.

When we reached the sea, we realized that it was a large community of seals – perhaps a hundred – lounging on the sands across from us. Their voices were loud now, drowning out everything else, and their song stirred something within me. Young seals dove from the shoreline into the clear blue water, swam and played, and then hopped back up on the sandy shoreline. That farther shore was an empty, flawless expanse of coastal wilderness, where the terns, seals, gulls and other creatures of the wind and sea would be free and safe. For a while at least.

As we turned and headed back to civilization, sand sifting through our toes, we felt blessed by the birds and beasts and privileged to have encountered this pocket of pristine wilderness, here in a land where human habitation goes back over 14,000 years.

~ Story by Lesley Choyce