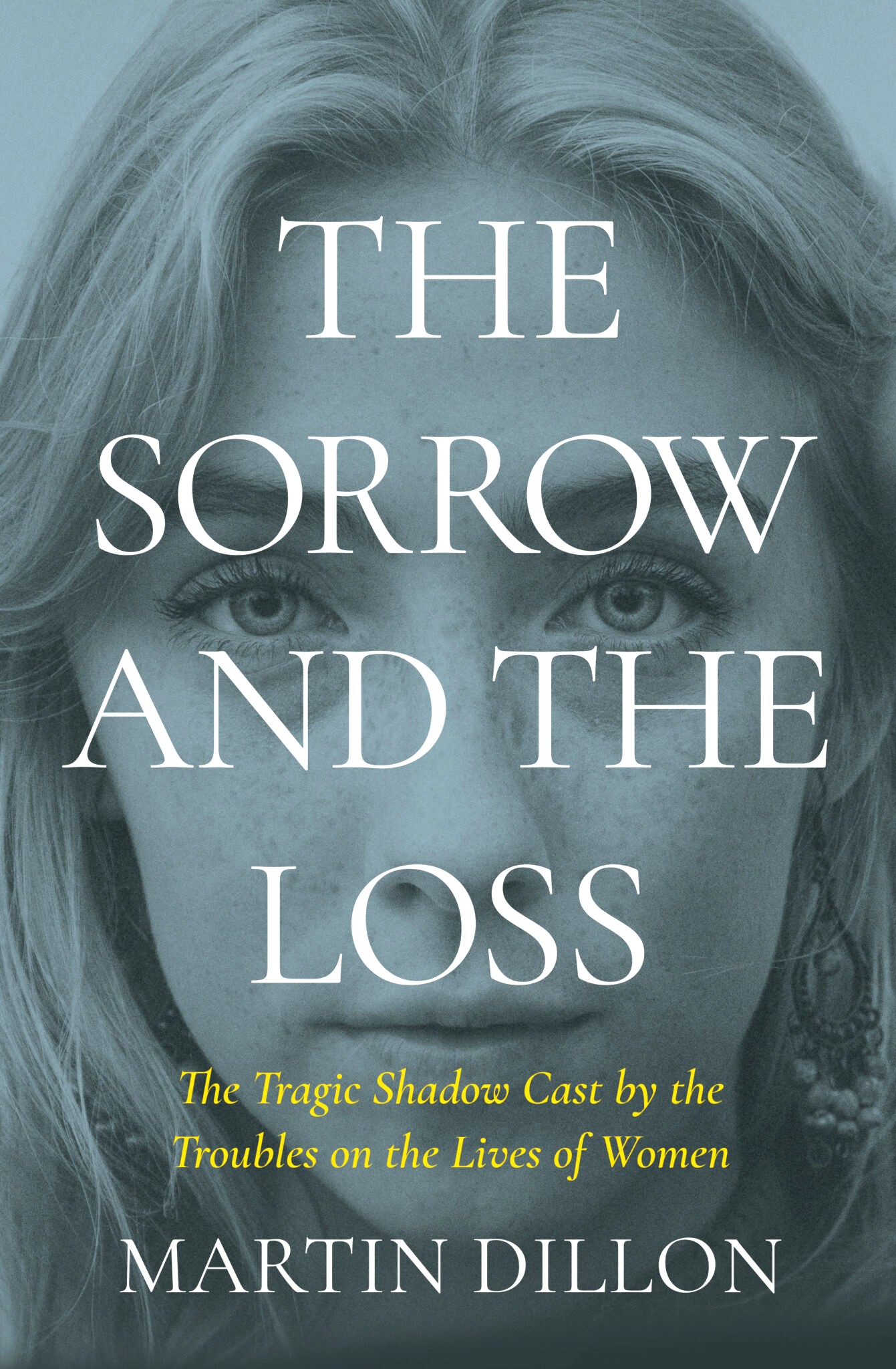

Longtime writer Martin Dillon says that out of all his books, his latest was the most “emotionally difficult” to write. In The Sorrow and the Loss, the Belfast native sheds light on the untold stories of The Troubles by focusing on the women who were affected.

“I wanted to look at all these women and find out, how did the conflict impact them? How did they find themselves in the middle of it?”

Dillon is a renowned expert on the decades-long conflict in Northern Ireland colloquially known as “The Troubles” or “The Long War.” In the late 1960s, long-held tensions spilled over into years of violence between Protestant unionists and Roman Catholic nationalists. Thousands were killed, from paramilitary fighters to civilians caught in the crossfire. The signing of the Good Friday agreement saw the end of the war in 1998. However, the ramifications of the conflict continued to reverberate, especially for the families of the dead.

The real depth of these people’s stories, shares the scribe, went under the radar for a few reasons – not the least of which was the fast-paced nature of news reporting during the war. “You’re chasing every event,” he recalls. “You don’t have time to be reflective.”

When Dillon finally did reflect, he realized those stories ought to be investigated further. “I thought that was one of the failures within journalism itself. It was being overwhelmed by the character of the events that were taking place.”

The author addressed this with his first book, Political Murder in Northern Ireland, which he wrote with Denis Lehane. Although he ultimately left his country for his own safety, Dillon continued to write about The Troubles as well as other topics, mainly related to war and crime. Then, even after many years of journalism under his belt and with a dozen books to his name, he realized that he was still been missing something.

“I had never reflected on the impact the violence had on women – the kind of trauma that they had been through and how many of them suffered PTSD…”

Dillon notes that most of the people writing about the conflict at its height were, like him, men. The stories usually focused on men as a result. “We tended to write about killers. Well-known terrorists,” he recalls. By neglecting women’s stories, he says, “I think journalism did fail them, in many respects.”

Many of the women depicted in The Sorrow and The Loss grieved partners, children, siblings or parents who died in the conflict. “A lot of them have never had answers, either. A lot of them don’t know who actually killed their loved ones, because so many of the killers, in many ways, were agents of the state.”

Bridget Kane was 24 years old when her husband, Edward, was killed in a pub bombing. As Bridget was never able to view Edward’s remains, she struggled to accept his death. “She went through terrible mental trauma. She didn’t want to believe – she thought, maybe he’s lost somewhere.” Meanwhile, her children had to pass the site of the bombing daily as they walked to school.

Tragically, the Kane family’s experience is far from unique. Many women sought the truth about the death of a family member and never received it. “That was the loss -apart from the loss of life, obviously.”

Other women, however, were involved in the violence itself. Mairéad Farrell was one such woman.

Once a student of Irish language and Irish dance, Farrell became a student of the IRA (the Provisional Irish Republican Army) as a teenager. During a stint in Armagh Prison, Farrell led a “dirty protest” and a hunger strike in solidarity with male IRA members in HM Prison Maze. Neither the media nor the IRA leaders took much notice of Farrell’s hunger strike, even though it almost killed her. Two years after her release from prison, Farrell met her end on the island of Gibraltar at the hands of British authorities.

“I wanted to know, what happened? How did young girl find herself in the midst of a conflict and drawn into it, as others were?”

Then, there are the women whose stories will never be told. Some spoke to Dillon but, ultimately, did not want to see their words published. One source feared it would worsen her PTSD.

Almost 30 years since the Good Friday agreement, the pain still lingers. But Dillon believes that knowing the history, as bloody and unpleasant as it can be, is as crucial as ever.

“If you don’t understand the past, the danger is it that it will be repeated…”

Leave a Comment