Ten Irish Books That Will Change You

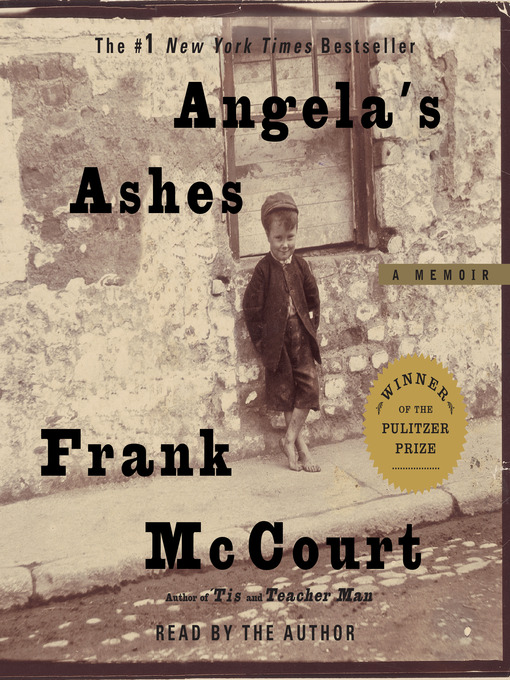

Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt

Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt

Five hundred years from now readers will still laugh and shudder at the privations and lonely passions of Frank McCourt. His late in life swan song was so startlingly rich and arresting that it beguiled the world and made him a late to the party overnight sensation. But McCourt, damaged beyond repair by a dysfunctional childhood, cast a cold eye on the celebrity that came his way and in return his old neighbors cast an even colder one on him. But no one – and I mean no one – can belittle his accomplishment, which is a tale to cure deafness and already belongs to the ages.

Tarry Flynn by Patrick Kavanagh

This could as easily have been called Portrait Of The Farmer As A Young Poet. Nothing about this author was inevitable. Born on a farm in rural County Monaghan, Patrick Kavanagh somehow saw past the low black hills that surrounded him all the way to Arcadia. In this book which is one part rural memoir, one part hymn and one part prison drama, Kavanagh explores all the tensions and attractions that produced him, and in particular the constantly thwarted sexual passions that were a feature of his 1930’s rural life. The clergy exist to separate you from your hearts desire he tells us, your neighbors exist to take delight in your misfortunes, your heart exists to break at the injustice of it all, and your head exists to record the pity of it. The world of Tarry Flynn is hilarious and harrowing, both familiar and increasingly strange, and it’s one of the best benchmarks of that era to gauge just how far we’ve come as a nation now.

The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats

Not just a collection but also an ionic cornice of civilization, Yeats’ achievement stands inside and outside of time. But to a young Irish person attempting make sense of their own heart he’s one of the first doors into the transcendence of love. Lost love, thwarted love, love grown bitter and enraged all vie here with lust, laughter and insatiable longing. “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire,” he writes. Generations of the Irish know his poetry by heart because that’s where it first makes its home.

The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde

With his innate suspicion of authority and his almost anarchistic freethinking, Irish teenagers are very fortunate to have Oscar Wilde as a guide to the attractions and absurdities of the adult world. They will find wit and wisdom in his Complete Works, but they will also catch more than a hint of melancholy too. In De Profundis, Wilde’s famous letter to his fatal and false love Alfred Douglas, he writes: “Most people are other people. Their thoughts are someone else’s opinions, their lives a mimicry, their passions a quotation.”It’s Wilde’s principled determination to be himself, even in the face of contempt that made him such a challenge to his era and all the eras to come. The kindest and most compassionate of men, as Richard Ellman said of James Joyce, we are still learning to become his contemporaries. To read his work is to enter into a more expansive world of brilliance and daring.

How Many Miles To Babylon? by Jennifer Johnston

The tragic intimacy of the Irish English colonial project is grey mirrored in the erotic friendship that flowers between the two unlikely friends in this exceptional book. Alec, the son of a prominent Anglo Irish family living on a County Wicklow estate at the turn of the 20 century, begins a forbidden friendship with local Catholic boy Jerry, who shares his passion for horses. Throughout Johnston conveys class and religious fault lines with enormous delicacy and she’s equally skilled at charting the senseless violence of the Great War and the thwarted passions of the men who fight it. The failure to connect is the only thing that unites here. It’s a lesson that will haunt you for life.

After Rain by William Trevor

Ordinary lives have something epic in them and ordinary life is William Trevor’s subject. The Piano Tuners Wives, the first story in his accomplished collection After Rain, illustrates this idea. “Violet married the piano tuner when he was a young man,” Trevor writes. “Belle married him when he was old.” That surface simplicity opens and opens until the domestic calm is quietly disrupted. Soon the struggle of the living wife to best the memory of the dead one achieves an almost fairy tale malevolence, but Trevor consistently remains aloof and impartial, allowing his characters to reveal themselves. By the stories end we understand that Belle will win this struggle with her dead rival, “because the living always do. And that seemed fair also, since Violet had won in the beginning and had had the better years.”

Are You Somebody? The Accidental Memoir Of A Dublin Woman By Nuala O’Faolain

Much of twentieth century Irish writing reads like dispatches from a penitentiary. O’Faolain grew up in Ireland in an era where female sexuality was feared and corralled by a reflexively conservative establishment that wore its hypocrisy like a badge of honor. The blatant sexism, the rigidly defined social roles, the sectarianism and misogyny of her era was her subject, and unlike others she placed herself at the center of her observations, making the political personal and often risking it all in a way that actually helped to change the nation that had oppressed her. In Are You Somebody we watch and cheer an emerging consciousness elude the nets cast to contain her.

At Swim Two Boys by Jamie O’Neill

The Easter Rising, the origin myth and narrative origin of the Irish Republic, exchanges places withUlysses in O’Neill’s absorbing meditation on the birth of our nation. Like Joyce, O’Neill is determined to add sexual freedom – but also love between men – to the list of idealisms that found his new republic, reminding us that oppression is not merely political. The disastrous face off between Edward Carson and Oscar Wilde (whom Carson prosecuted and ruined) is also thematically echoed in the book, reminding us that the central ideas that decided Irish nationhood are more expansive and compelling than many historian like to inform us.

A Modest Proposal by Jonathan Swift

The cruelty and horror of colonial exploitation have never been better skewered than by this Anglo Irish master satirist. Although he’s better remembered for Gulliver’s Travels, Swift made his outrageous suggestion that the Irish poor sell their children as food to the English rich whilst deriding the solutions that he actually believed in: “Therefore let no man talk to me of other expedients… taxing our absentees… using nothing except what is of our own growth and manufacture… rejecting foreign luxury… introducing a vein of parsimony, prudence and temperance…learning to love our country… quitting our animosities and factions… teaching landlords to have at least one degree of mercy towards their tenants…. Therefore I repeat, let no man talk to me of these and the like expedients, ’till he hath at least some glimpse of hope, that there will ever be some hearty and sincere attempt to put them into practice.”

Happy Days by Samuel Beckett

Although strictly speaking a play, and not necessarily regarded as one of Beckett’s finest, there is something about Happy Days extended metaphor (which critic Kenneth Tynan thought had been extended beyond its capacity) that deeply resonates for the Irish. Cheerfulness in the midst of horror, a strange comfort with mystery in the midst of the mundane, these are contradictions that the Irish have been forced to live with for so long that they can now accept them without a shrug. “Just to know that in theory you hear me even though in fact you don’t is all I need,” says his character Winnie. That’s exactly how most Irish conceptualize God. And in a nation where magical thinking can achieve epidemic proportions, that sentiment echoes still.