The Softness

While the Wild Atlantic Way is an apt name for Ireland’s rugged northwest counties of Sligo, Mayo and Donegal, the trail’s southwest counties of Galway, Clare and Kerry invite travelers on a gentler journey.

While the Wild Atlantic Way is an apt name for Ireland’s rugged northwest counties of Sligo, Mayo and Donegal, the trail’s southwest counties of Galway, Clare and Kerry invite travelers on a gentler journey.

The route south from Galway to Killarney is highlighted by sloping roads through rolling hills, lush landscapes, and hushed forests, by trickling streams, quiet lakes and small waterfalls. Sheep, goats, horses and cows graze lazily in farmer’s fields and on mountainsides – most are silent spectators, immune to the human race taking place on the region’s motorways and back roads.

Drivers here are courteous, and civil. Area road signs, both in English and Gaelic, politely remind those behind the wheel to watch their speed. One clever billboard near Billybunnion casually spells out the region’s road rules with a simple Tóg Go Bog É – Irish Gaelic for ‘Take it Easy’.

The mood here is light and relaxed, a reflection of a people at ease with themselves. A closer look sees that soft sensibility infused into every aspect of their daily lives.

Restaurants in and around Galway cater to a milder palate, with a swath of light goat cheese, soft artisan bread, scrumptious seafood, and tender meats available at all hours. A good pint of Guinness makes a creamy compliment, and Irish whiskies are ideal for smooth after-supper sipping.

This tempered taste can be attributed to the use of all-natural ingredients and local produce, farmed and fished from soft soil and water that has remained unspoiled for centuries.

Nature seems at ease here also; in County Clare, the big sky over the Cliffs of Moher brings soft rain and gentle mists. South, in County Kerry, wisps of cottony clouds cover hilltops near Tralee. A few miles west, waves wash over the shore all around the spectacular Slea Head on the Dingle Peninsula, with small puffs of sweet turf smoke arising from fireplaces in roadside homes and cottages.

The music, also, is without edge; nightly ‘seisiúns’ at pubs in Doolin and Dingle showcase the lovely lilts of Irish melodies, the soft strumming of guitars, shimmering tin whistles, the fine finesse of fingers upon fiddles, and the angelic voices of those who carry the tunes and traditions of their forefathers.

The music, also, is without edge; nightly ‘seisiúns’ at pubs in Doolin and Dingle showcase the lovely lilts of Irish melodies, the soft strumming of guitars, shimmering tin whistles, the fine finesse of fingers upon fiddles, and the angelic voices of those who carry the tunes and traditions of their forefathers.

Similarly, softly-spoken Gaelic seamlessly rolls off the tongues of residents in Rathkeale, Cahirciveen and Lisdoonvarna.

And while both music and language may be windows to the Emerald soul, the Irish are a people whose kindness, civility, and homespun hospitality are rooted in the land, sea, and sky. Nowhere will the visitor feel more at home than along the country’s soft southwest coast.

Passing through the timeless villages of Kenmare and Macroom near the Ring of Kerry, it is easy to understand the longing for home felt by so many ex-pats around the world.

Many of those people – 3 million between 1851 and 1970 – would leave Eire from the harbour town of Cobh in the south. The quaint community, just east of Cork, might be best known as the last port of call for both the ill-fated Titanic and Lusitania ocean liners.

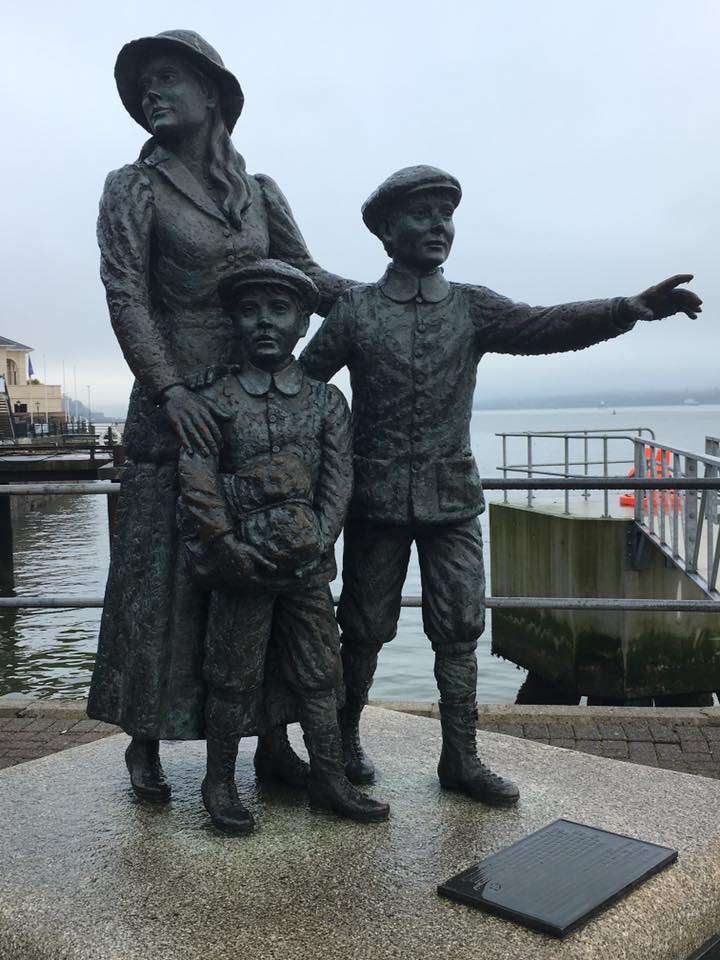

The Cobh Heritage Center along the city’s waterfront is a bevy of information on Irish immigration; displays, interactive exhibits, short films, and more, detail the terrible trials of those forced to flee the Emerald Isle because of famine, poverty, oppression, and injustice.

There are tales of triumph too, including the story of Annie Moore, the first Irish immigrant to be processed at Ellis Island in New York in 1892. Moore built a new life for herself in the new world, as did tens of thousands who followed in her footsteps. The Heritage Center celebrates those successes, listing names of notable politicians, religious leaders, captains of industry, entertainers, artists, and social activists who bade farewell to home for greater fortune on distant shores.

There are tales of triumph too, including the story of Annie Moore, the first Irish immigrant to be processed at Ellis Island in New York in 1892. Moore built a new life for herself in the new world, as did tens of thousands who followed in her footsteps. The Heritage Center celebrates those successes, listing names of notable politicians, religious leaders, captains of industry, entertainers, artists, and social activists who bade farewell to home for greater fortune on distant shores.

The tragic far outweighs the triumphant here, however. In truth, the country’s history, heritage, culture, and identity – some might say the very heart and soul of Eire – was sent out into the world from Cobh’s cradle. The site’s small docks were scenes of endless tears, heartache and grief; “living wakes” were daily ritual for generations of families, as they said goodbye to loved-ones, likely never to see them again.

Here, that sense of sadness and sorrow still sits like a soft Irish mist over all; a lingering remnant of a past that permeates the present – it is a different sort of softness, however; perhaps more of a gentle melancholia.

Now, as I prepare to leave this lush land, this ancient abode of my ancestors, I feel it also.

~ Stephen Patrick Clare