The more you study the history of the Scottish Highlands of the 18th and 19th centuries, the more upset you become. It is impossible not to be deeply moved by the violence, betrayal, upheaval, and general difficulty experienced by the Highland clans during this time in their history.

Since as far back as the 12th century, families in Scotland were organized into networks, called clans. The word clan comes from the Gaelic meaning “children.” Most clans had a chief, and families paid homage to their leader, living off his land and paying rent in kind in return for protection and alliance. Families often took on the name of their clan chief as a symbol of their loyalty. Clan life in the Highlands of Scotland was a lot different than life today. Most clan family homes had turf walls, with rafters of stout branches thatched with straw, bracken, or heather, and stamped earth floors. Fuel wasn’t purchased – it was free from the peatbanks. Clothes were handwoven of wool or flax. Furniture, crockery, and cutlery was sparse and handmade. Journeys took days, and the most common foods taken on the road were oats, bannocks, the occasional salted meat, and always whisky!

By the end of the 17th century, Scotland was in a period of transition, about to give up its parliament as it had given up its sovereign crown in 1603. A troubling era of religious persecution against the Scottish covenanters ended when William of Orange, a Protestant and grandson of Charles I, took the throne with his wife Mary. However, many Highlanders were Catholic and a number supported the royal House of Stuart.

Between 1688 and 1746, a number of uprisings occurred in an effort to overthrow the Hanoverian royal line in favor of a Stuart king. Supporters of these “rebellions” were called Jacobites, after Jacobus, the Latin form of James, a popular name in the House of Stuart.

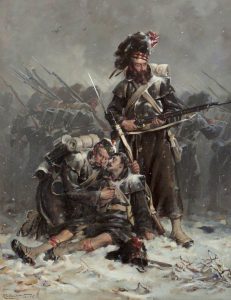

The final uprising, the ’45, culminated in the Battle of Culloden, fought on Aprl 16th, 1746. It was the last pitched battle fought on British soil. It pitted a Jacobite force comprised of Highlanders, some lowlanders, and some French, against a government force of mostly English and some Scots and Irish. The Jacobites were led by Prince Charles Edward Stuart, or Bonnie Prince Charlie, a claimant to the throne from the House of Stuart.

After advancing into England, the Jacobites returned to Scotland and met the government forces near Inverness, in the Highlands. The government army, led by the Duke of Cumberland, was larger, more provisioned, more organized, and likely more rested than the Jacobites. The battle occurred on the marshy fields of Culloden. It was short and bloody. Without being able to establish a Highland charge or engage in guerilla warfare, the Jacobites were quickly overwhelmed by government artillery. In the space of an hour, between 1500 and 2000 Jacobites were wounded or killed, as opposed to the government’s 50 deaths and around 300 wounded. The aftermath of the battle was equally brutal, as Cumberland the Butcher ordered survivors to be hunted down and killed. Many innocent people in the region were killed or harmed. Homes were burned and livelihoods dashed. Some Jacobites escaped, others were

executed in England. A number of them fled to the Americas or served in other campaigns in Europe. Prince Charles escaped and went into hiding, eventually ending up back in France, never to return again.

Soon after Culloden, laws were passed that banned Highlanders from wearing clan colors or bearing arms. The Gaelic language was marginalized by officialdom. Clans lost land and power. The clan system suffered irreparable harm. Truly, Scotland changed forever during this period. And then the Highland clearances began. In the space of 50 years, the Scottish Highlands became one of the most sparsely populated areas in Europe. The Highlanders immigrated far and wide, across the globe in search of a better life. Today, there are more descendants of Highlanders outside Scotland than there are in the country.

Leave a Comment