A Song for Father Francis ~ Part 1

My mother believed she would sit in purgatory, a fiery spot located between heaven and hell, for a good long time being purged of her life’s sins before she could enter, in a glorious resurrected state, into the kingdom of heaven. So it is nothing short of reprehensible that I have not delivered this money, given for masses at the wake and funeral to be said for her early release from there.

My mother believed she would sit in purgatory, a fiery spot located between heaven and hell, for a good long time being purged of her life’s sins before she could enter, in a glorious resurrected state, into the kingdom of heaven. So it is nothing short of reprehensible that I have not delivered this money, given for masses at the wake and funeral to be said for her early release from there.

I am feeling embarrassed and guilty. Though, I suppose, the guilt had to grow to outweigh the reticence I feel for going to the monastery. An ancient reticence composed of old furors – actually, young furors grown old; the most virulent kind. An adult can speak her mind or at least absent herself from an onerous situation. A child, vulnerable without forum or options, must endure, which is why exorcising childhood neuroses is like uprooting hundred-year-old trees, and often requires the personality equivalent of a bulldozer or an end loader.

When my father was alive we went to the monastery for mass and to drop him off or pick him up from retreats. Men made retreats there. Boys, (my bratty brothers) were allowed to tour the monks’ cells, the refectory, apiary, bakery, (sample fresh bread and honey), wine cellar, orchard and barnyard. Women and girls were not permitted past the religious goods store and chapel, where the monks were singing the Gregorian chant whenever we arrived. Never a woman’s voice was heard.

The only priest with whom I am on speaking terms these days explains, “The church has changed vastly.” And I am unable to make him understand that does sweet nothing to ameliorate the feelings of helplessness and furor I felt standing in the corner next to the shelves in the monastery store between the stacks of missals, boxes of medals, rosaries, bottles of holy water and statues of Theresa, Anthony, Joseph, and all the rest, biting my lower lip, locking my knees hard and hating being kept out.

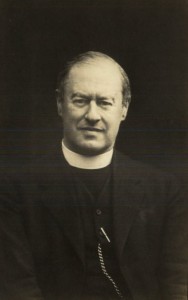

The human object of my hate was the tall, alabaster-faced, tonsured Father Francis, who had the same kind of eyes nuns at school had—stare-you-through eyes, always blue, the cold-sky blue of a below-zero day. I figured they set him as a guard to keep us from going where we weren’t allowed because he had white skin like a woman. But he was a man and a priest with all the prerogatives that implied. He wore a cream-colored cassock, in place of the black one most priests wore, and over it, a brown scapular, which reached to the floor and had a little hood on the back which would never fit over his big, ugly head. No, he was a man – I always knew that when he laid his heavy, sweaty man’s hands, like ten-pound sacks of sugar, on our heads to bless us. And I shuddered.

I’ll be honest: I have chosen this day because I am feeling mean, because now the enervating heat of summer has passed, the air has that sharp, crisp edge of autumn that energizes, and I am ready for him.

New Truroe Abbey, less than ten miles from this village, is an enclave of stately limestone buildings which, when I was a child and a history idiot, I always imagined resembled a castle. Turning left off the highway, I find myself on a gravel road through a walnut grove. The lands of this Cistercian abbey extend all the way to the county line – twenty-five hundred acres. After a few miles, the grove gives way to hilly hayfields, golden in the fall sunshine. In another mile or so, the neat fields become gardens with expanses of squash, prodigious stands of onions, broccoli, carrots, and Brussels sprouts, all surrounded by white board fences that look more as if they should restrain Kentucky thoroughbreds or at least Connecticut cows. Fat-cat fences. Iowa farmers use barbed wire. This only augments my anger.

A right turn by a large horse-chestnut tree brings me onto the circular, tree-lined drive of the monastery. The place seems deserted. Then I realize, with a metallic ping of disappointment someplace in my brain, that I probably won’t get to tell Father Francis to stuff his blessings. It’s been thirty-five years; he’s probably dead. I park the car and get out, kick a stone onto the grass and turn toward the stained glass entry door, listening to my heels click acrimoniously against the tarmac.

Inside, I hear only echoes of silence, not chanting, and make my way down the short hallway to the store, pausing before the door to pull myself up to full height. An old, bald monk seated at the center of the room looks up from the missal on his knees and smiles as if he’s totally delighted; as if, indeed, he has been waiting for me.

“Come in, Child,” he says in tones so rich and warmly Irish, I am momentarily caught completely off guard.

“I’m Bridget McMahon’s daughter,” I say, smiling coldly, standing stiffly erect behind the chair he’s indicated. I produce the money, leaning forward from the waist to hand it to him.

“Ah, yes, we heard she died in June. She was with us on Paddy’s Day.”

She was. Women not only are allowed in the refectory now, they eat there.

“It was one of the last days she really felt well; she enjoyed herself immensely,” I say, and on seeing him smile, become angry I’ve given him that and grip the back of the chair with new resolution.

“Now would you hand me the mass book over there? The feet aren’t what they once were, sure,” he says pointing toward the shelves back and to the left of me.

Glancing at the shelf to reach the red spiral notebook with MASSES hand-printed on the front cover, my gaze falls into the corner where I used to retreat with my anger, and for a moment, I visualize myself there, a stiff-kneed and furious little girl in a plain homemade dress. I look back, about to say, “Get it yourself, Father Francis!” Then I spy his red, swollen, buniony feet with their thick yellow nails protruding from beneath the accumulation of cassock and scapular – clearly too painful for shoes, they are in open sandals. Reflexively, I dash across the room, fetch the notebook and hand it to him. While he counts the money, records my mother’s name and the amount in large hand beneath the names of two others recently deceased, I stand regretting having done it.

“Ah-hah, so you are Michael’s eldest daughter,” he says, when he’s finished and closed the mass book.

It has been thirty years since my father died, and I’m astonished he remembers his name, but he has a reputation for this. “Do you really remember my father?” I ask, suspicious.

“Michael McMahon, a fine and decent man, and a great one for a story.”

“What—what sort of stories did he tell, about what?” I am curious in spite of myself.

“Sit, Child, and I’ll tell ya.” ~ Story by S. Keyron McDermott

Part 2 tomorrow!

Leave a Comment