Ancient Treasures of Wales

Between the 11th and 14th centuries AD, the Kingdom of Man and the Isles dominated the Inner and Outer Hebrides, Skye, Argyll and the Irish Sea. The rulers of this territory were based on the Isle of Man, from where they controlled the vital sea route that allowed the trading of items such as rare, carved chess pieces, silver coins and symbols of religious power. Here, Celtic Life International contributor Valerie Caine takes us inside a recent exhibition that returned some of the treasures of this largely forgotten era to the island’s Manx Museum in Douglas.

Between the 11th and 14th centuries AD, the Kingdom of Man and the Isles dominated the Inner and Outer Hebrides, Skye, Argyll and the Irish Sea. The rulers of this territory were based on the Isle of Man, from where they controlled the vital sea route that allowed the trading of items such as rare, carved chess pieces, silver coins and symbols of religious power. Here, Celtic Life International contributor Valerie Caine takes us inside a recent exhibition that returned some of the treasures of this largely forgotten era to the island’s Manx Museum in Douglas.

One of the most important documents to be written on the Isle of Man, The Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles was composed in Medieval Latin, probably by monks at the island’s most important medieval religious site, Rushen Abbey in the island’s south. Still in remarkably good condition, the document’s closely knit but legible text sits upon pages darkened with age, allowing glimpses into the past, and bringing to life the battles, kings, revenge plots and political skulduggery and ecclesiastical concerns of Manx history.

Although recently part of the exhibition held at the Manx Museum, the document is usually housed in the British Library in London. How and why this manuscript came to be in the hands of people outside the Isle of Man is open to speculation. Campaigns to have the document returned to the island remain unsuccessful.

Speaking of the exhibition, Tony Pass, Chairman of Manx National Heritage, credited close collaboration between Manx National Heritage, the British Museum, the British Library and National Museums Scotland for securing loans of precious objects, some of which had not previously been seen on the Isle of Man.

The Chairman said the exhibition shed light on a significant, but so far obscure period in the island’s story. “It tells of a time when we were the capital of a maritime kingdom, extending from the Celtic Sea into the North Atlantic, when trade brought wealth, and wealth supported sophisticated art and skilled craftsmanship,” he said.

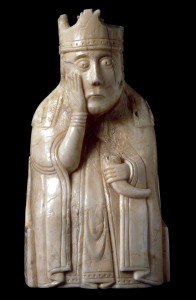

Visitors to the exhibition were excited to find six pieces of the fabled Lewis Chessmen set on display. The Lewis Chessmen is a truly unique chess set; the intricately carved pieces are thought to have been made c.1200AD in the city of Trondheim in Norway.

The 78 pieces were carved on expensive pieces of walrus ivory as well as the occasional tooth from a sperm whale. Some of the pieces were originally stained red, suggesting that the medieval game of chess adopted a different colour system from its modern counterpart.

Discovered by accident on the west coast of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, probably during the early nineteenth century, the visiting chessmen are normally housed in the British Museum.

Exhibition visitors enjoyed the pieces’ remarkable individuality of expression, style and apparel. They saw a king who wears a serious, almost comical expression as he sits on his throne, while maintaining a tight grip on the hilt of his sword. His queen has long, braided hair covered with a veil underneath her crown. She looks discontented or contemplative as she holds a hand to her face. The knight is portrayed astride an exaggerated Scandinavian horse of the era and the warder carries all the hallmarks of the fierce, wild-eyed warrior known as the berserker, while the pawn sits eloquently in its simplicity.

Where the chess pieces were destined for when they were lost remains a mystery. As a hub of international trade, the Kingdom of Man and the Isles was home to many wealthy people, and the island of Lewis may not have been the final destination of the chessmen; they may have been on their way to the Isle of Man.

The exhibition also revealed details about archaeological discoveries which point to other games played socially during this period on the Isle of Man, with simple gaming boards recovered from the areas of Block Eary, Druidale and Cronk ny Howe on the island. And despite the church frowning upon gambling, a number of dice were excavated at Rushen Abbey.

The church, which at this time was part of the archdiocese of Trondheim in Norway, held a powerful influence over people from all walks of life, including the Kings of Man and the Isles who wavered between ruthless behaviour and the need for salvation.

Although far from harmonious, the communities within the Kingdom of Man and the Isles inevitably blended a diverse range of cultures as people from both Gaelic and Norse traditions learned to live together, which is reflected in both family and place names. But, as this period of history drew to a close, one major difference did emerge as the Isle of Man favoured a Scandinavian parliamentary system as opposed to the Scottish Gaelic system which dominated within the other islands.

The Speaker of the House of Keys, Steve Rodan MHK, said that although the Kingdom of Man and the Isles may well have been forgotten over time, it is central to the island’s modern identity.

“That we uniquely have our own legislature, Tynwald (parliament) and our own laws and government is thanks to that Viking legacy,” he said. “The Kingdom deserves to be remembered, and Manx National Heritage has done an excellent job in reviving that ancient memory before the public…in putting together a superb exhibition which stands comparison for its content and quality of presentation with any museum display anywhere.”

Leave a Comment