“This is a ridiculous place to be standing,” says Andrew Scott, in front of a poster of Andrew Scott, bearing the words ‘ANDREW SCOTT.’

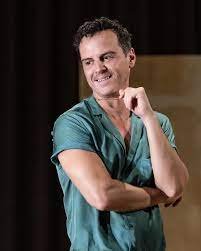

We are outside the Duke of York’s theatre in London, where Scott is in the middle of an acclaimed run of the Anton Chekhov adaptation Vanya. Scott himself is a little delirious. You could put it down to the eight times a week that he stands alone on stage here for 100 minutes. He wakes up every morning with these giant puffy eyes, his body fraying from the endurance feat of playing all eight parts. “It’s like going into a fever dream when you go on stage,” Scott says. Even worse is the time away from the theatre, when he carries the characters around like little animals that need to be held close to your heart. But every night – and some afternoons, too – he walks on stage and turns out the lights, flicking them back and forth to see the audience’s faces strobing in the darkness like apparitions. It gets him every time: the moment of everyone holding their breath before the story begins. As he says, “It’s not nothing.”

Performing so often means that Scott’s days and nights are now a frenzy of fitting his life into the small moments left over. As such, time has taken on an almost supernatural quality, Scott’s world temporarily shrunk to the few streets around the theatre, and so jostling through the crowds of the National Portrait Gallery, as we had planned to do this afternoon, feels like a waste of it. So we head inside – which turns out to be an even more ridiculous place to be, as the people there, likely chancing their arm for a return ticket to see Scott tonight, are startled to see the star himself enter. I am treated to a brief one-man show of Scott buzzing around the bar and desperately trying to hide, which culminates, in Chekhovian farce, with us hiding in a stairwell.

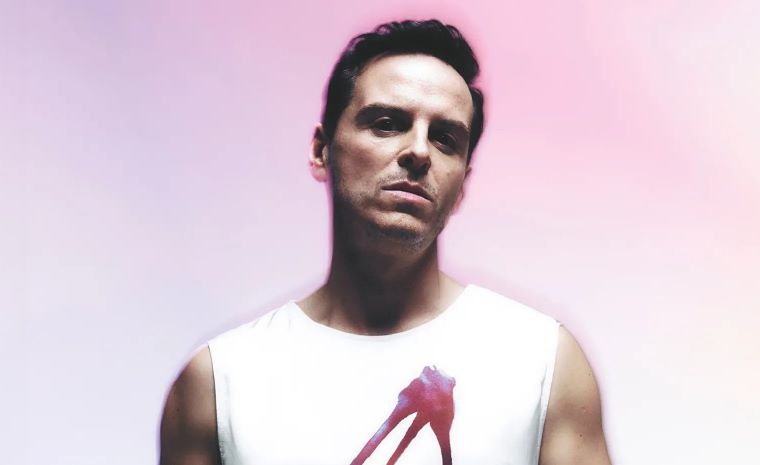

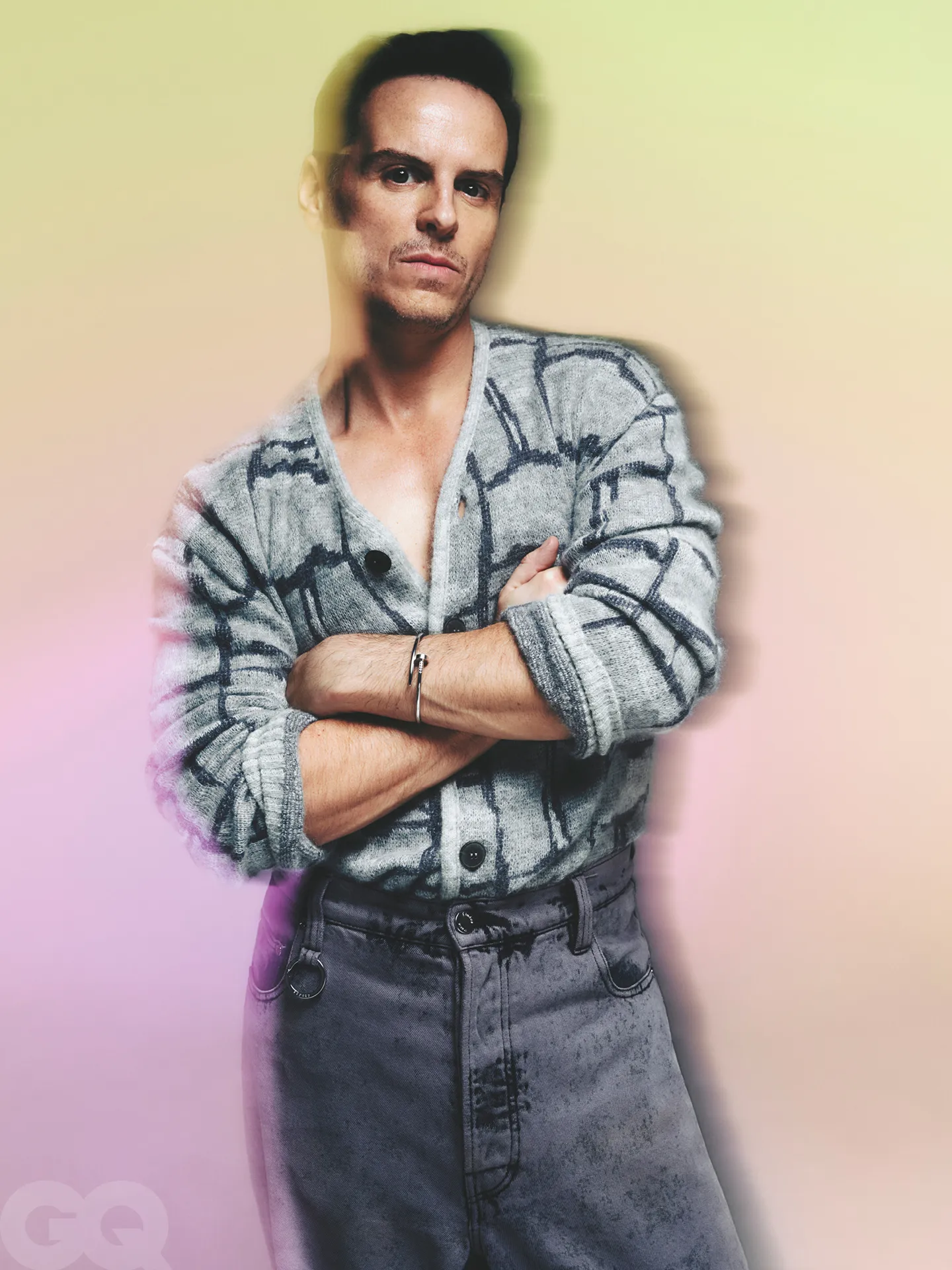

We eventually find a shadowy bar beneath the stage where Scott sits cross-legged on a chair. He is boyishly handsome for 47, today wearing a grey T-shirt, shorts, and trainers with his socks pulled up. He has a tender way of talking, and an unfaltering way of maintaining eye contact that makes you feel like Scott is telling you a secret delivered as a bedtime story.

“These old theatres are absolutely beautiful, I love them,” Scott says, taking in the room quietly. “It’s like all the greats that have been here. These old buildings [are] steeped in history.” Scott thinks the building is filled with the ghosts of all the actors before him. This sense, of the ghosts of performances past, was recently brought to life when a fan approached Scott with the playbill from a production of Chekhov’s play performed here at the same theatre some 100 years ago.

Vanya was reimagined into a one-man show by accident. Scott had been reading through the script with director Sam Yates and co-creator Simon Stephens, trying to work out which part he might suit. With just three of them in the room, Scott ended up reading several parts, when something unexpectedly brilliant happened. When Scott left the room, the other two gave each other a look; Scott got the role, and the trio reworked the script to accommodate one person playing all eight parts. The mammoth line-learning Scott had to do as a result this summer was another kind of fever dream. “There were lots of people moving their children away from me on the Tube,” he says with a dark smile.

Scott’s performance in Vanya is an extreme version of the kind of shapeshifting that the Irish actor has done throughout his career, moving with ease from high camp theatrics to disturbing villainy. Successive casting directors have witnessed his unsettling ability to flit between humour and vindictiveness; others, in those dark eyes, see something tender and wounded. It was that softness that prompted Phoebe Waller-Bridge to conceive the role of the priest in Fleabag (“He’s not called the hot priest, sexy priest, whatever the fuck it is, in the script”) with Scott in mind, having previously worked with him on the 2009 play Roaring Trade. “At the time people would be like, ‘What? You want the psycho from Sherlock?’” he says. “But Phoebe saw something in me that I really wanted to express.”

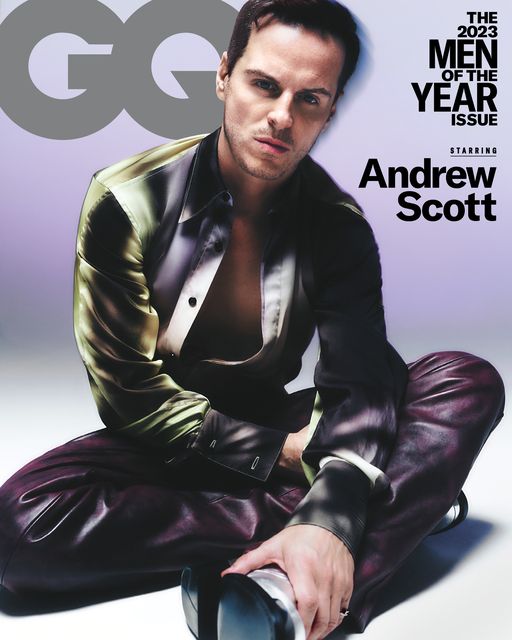

This winter, Scott will play against himself again in Andrew Haigh’s All of Us Strangers, a gorgeous, ghostly love story, which even as we meet is already inspiring both Academy Award murmurs and deeply personal responses from early audiences for its exploration of grief, sexuality and where those two things sometimes meet. There’s also Ripley, a new Netflix adaptation of the Patricia Highsmith novels, which trails Scott as the solitary murderer with a watchful eye. Both projects are leading roles, a rarity for Scott, who on screen at least, has tended to play supporting roles to bigger stars (Cumberbatch, Waller-Bridge, Bond’s Daniel Craig). Although very different, both also see Scott showcase his talent for capturing the yearning inside people — the kind of men who were never invited to the party.

Scott’s career as an actor thus far has painted in big, bold shades, but this next stage feels like something deeper. As he says, “I like when the colours are a bit more dark.”

Every four or five weeks, Scott returns to Dublin, to see his family and take long walks along the coast. He was born there, his mother an art teacher and his father working at a youth employment agency; Scott the middle child between two sisters. Their house was on a suburban cul-de-sac where he played in the road with his neighbours. As a baby, Scott would stage one-man shows from his playpen, talking to different objects and keeping himself entertained for long stretches of time. As he got older, though, he became shy and struggled with a lisp, and at around eight years old he was encouraged to attend drama classes as a way, as he puts it, to open himself up from being “very clenched-fisted.”

Acting helped Scott to unfold and find his voice; he took up youth theatre camps, and at 17 landed a part in Cathal Black’s 1995 drama Korea. Enlivened by the experience of working, Scott came home and gave up a bursary to attend art school and took up drama at Trinity College. Then he did it again, leaving studying behind to take a series of roles at the Abbey Theatre. A restlessness drove those early years; Scott would frequently catch early morning Ryanair flights from Dublin to London to meet casting directors, navigating his way around with a Tube map inside a Filofax, before flying home that same evening. Shortly after moving to London he made his theatre debut at the Royal Court in Conor McPherson’s Dublin Carol. Vanya co-creator Simon Stephens used to tell students about seeing a young Scott in the play, and how, even standing alone, Scott seemed to fill the stage. “I found it almost unspeakably haunting,” he says now. “This was 23 years ago, but he’s always had this extraordinary capacity to just be on stage and be human.”

During those years Scott started landing bigger roles in film and TV, including with Steven Spielberg, twice, in Saving Private Ryan and then Band of Brothers. He worked alongside Julianne Moore and Bill Nighy in Sam Mendes’ biting play about the Iraq war, The Vertical Hour, on Broadway; and opposite Ben Whishaw in the Royal Court’s staging of Cock, which won an Olivier Award.

But it was playing the unnervingly calm villain Moriarty in the BBC series Sherlock which awakened audiences to his depths as a performer. “It was like nothing I’d seen, the way that he can change from completely charming to completely chilling,” series co-creator Mark Gatiss recalls of Scott’s audition. “There’s something electrifying about him and his dark eyes – they can be soulful and frightening all at once.” Watching the show back, Moriarty features surprisingly little in Sherlock; Scott became obsessed with cutting his lines down and never raising his voice, so that he didn’t give away his power. But Gatiss felt the “long shadow” of Scott’s performance haunted the series, meaning that “even after we killed him he wouldn’t die.”

When the final episode of season one aired, with Moriarty revealing himself in the show’s climactic swimming pool scene, Scott was in the middle of rehearsals for a production of Noël Coward’s Design for Living. He went into work on Monday morning to discover that everyone was suddenly looking at him differently. (Gatiss recalls being subsequently cornered by casting directors who told him: “You bastard, I wanted to discover Andrew Scott.”)

After playing Moriarty, it was perhaps inevitable that Scott was offered a role as a Bond villain, in 2015’s Spectre. His character, C, riffed on the understated menace which he had mastered in Sherlock, but the part didn’t sit right with him. “If I’m honest, it’s not a territory that I feel like I would want to go over again. Now I know who I am a little bit more, I feel like the work that I’m just interested in doing is more in the grey areas,” Scott says. “I suppose it’s just that I didn’t think… I just maybe wasn’t that good in it.”

If Moriarty had supersized Scott’s fanbase, then Fleabag sent it into delirium. One much-quoted stat is that Scott’s performance as the priest single-handedly increased searches for religious porn by 162 per cent. “It was full-on, it was definitely full-on,” he says. The show conquered America and won several Emmys in the process. Waller-Bridge famously wrote an alternative ending to the show, and swore to tell nobody; but she did confess it to Scott. No, he won’t say what it was. Yes, he does believe she chose the best one: “I genuinely think it’s completely perfect.”

In the way that appointment TV shows do, Fleabag continues to linger online in Instagram supercuts, with Scott’s performance held up as one of the archetypes of internet thirst, though he doesn’t seem to mind. “I think there’s a difference between objectification and admiration. So no, I didn’t, it didn’t ever bother me.”

But experiencing that level of fame has made Scott tentative about revealing everything about himself. “I never shy away from showing the ugly side of myself or the ridiculous side of myself or the really fragile parts of myself,” he says. “But I think if you’re going to do that then you don’t give all of it.”

In All of Us Strangers, Scott plays Adam, a reclusive screenwriter living in a London tower block, deserted but for the distraction of the charming and fragile Harry (Paul Mescal), with whom he begins an intense, intimate relationship. The story is based on the novel Strangers by Taichi Yamada, in which the protagonist revisits his late parents’ home in the suburbs only to find them alive and unchanged from the day that they died. Adam drifts between reality and the supernatural, a stranger in both past and present and unable to stay in either for long. Scott’s performance is so sincere and exact that at times it feels painful to watch.

“He is a sensitive person,” says director Andrew Haigh, who also helmed the stirring romantic dramas 45 Years and the HBO series Looking. “When you’re a sensitive person you understand loss and pain and things in your life you wish had been different. All of those things are essentially ghosts.”

Haigh says that he and Scott went into the shoot “holding each other’s hands”, such was the intensely personal nature of the experience. “I broke out with eczema during the shoot, which I haven’t had since I was a kid,” Haigh says. “It was just the strangest thing, something inside bursting to the surface.”

The scenes where Adam returns to his parents’ house were shot in Haigh’s own childhood home in a suburb outside Croydon. Scott remembers walking around the house, which had been filled with the same magazines that he had grown up with. He sent photographs he took inside the house to his sisters, a ghost wandering through his own memories. Making the film was cathartic for Scott; like Haigh, he brought his own pain to the table. “I wore some of my own clothes,” Scott says, his voice dimming as he pulls out the chain around his neck, the same one that he kept on while filming. “I didn’t want to act.” Haigh remembers watching Scott revisit his own past on set, when he picked up toys in the character’s bedroom. “It’s so interesting watching someone react to something because you can see on their face they’ve been dragged back,” Haigh says. “It’s like time travel.”

In one scene in All of Us Strangers, Adam comes out to his parents with both the innocence of youth and the experience of adulthood. The film, Scott believes, is about getting “a second chance” to have “a very clear, pure conversation about something, whatever the something is, with your parents.”

But as it shows, coming out is often not a uniformly good or bad experience – despite the tendency in drama to flatten it into one or the other, it can be a mixture of both, and neither. For many people, Scott thinks leaving that conversation is like walking away from a car crash and trying to work it out if you are leaving with a bump, or as wreckage. “I had a very happy childhood,” Scott says. “But there’s an inevitable pain that you have to go through when you have to take a risk telling your family something about yourself. I really do think that that is a gift now, because to have to risk everything, and for your family and friends to say ‘we accept you no matter what,’ that’s a real feeling of love that you get confirmed at a very young age, that actually some people who aren’t queer don’t get. I mean, some queer people aren’t so lucky.”

“There’s an inevitable pain that you have to go through when you take a risk telling your family something about yourself.”

“There’s an inevitable pain that you have to go through when you take a risk telling your family something about yourself.”

Homosexuality was illegal in Ireland until Scott was 16, and growing up he witnessed the media demonising gay people in the wake of the Aids epidemic. Scott’s teenage years were difficult, as he grappled with his sexuality and how it complicated things. “There was so much of me that was quite fearful, actually, and ignoring that side of me,” he says. “What’s difficult sometimes for gay people is that you don’t get to experience this sort of adolescence where you go, ‘Oh, my God, I like that person, do they like me back?’”

For Scott, making All of Us Strangers was his own chance to revisit and address some of those feelings. “I think that’s maybe why this feels so gratifying and cathartic,” he says. “Because I did have to bring so much of my own pain into it.”

For years as an actor he had listened to advice that he should keep his sexuality private. “I was encouraged, by people in the industry who I really admired and who had my best interests at heart, to keep that [to myself],” he says. “I understand why they gave that advice, but I’m also glad that I eventually ignored it.”

In 2013, with growing recognition bringing with it increased press attention, Scott came out in an interview in The Independent. “Sometimes I find the prurient nature of the way we talk about it a little bit exhausting,” he says. “It’s both very important to talk about and sometimes I feel like I wish we didn’t [end] up talking about it.”

Depictions of gay relationships on screen and stage have historically tended to focus on the trauma and pain that can come with those experiences. But a new wave of storytellers are focusing on the tenderness of all kinds of sexuality with the same wide-eyed joy as straight coming-of-age stories. Scott references shows such as Heartstopper for giving the current generation the experience of seeing themselves represented in a way that feels both novel and important. “I just think it’s so wonderful that people can see themselves,” he says. “There’s a sort of hysteria about it, [but] different forms of sexuality have existed since the dawn of humanity.”

In All of Us Strangers, that buoying love lifts two lonely people from their own pain. “I’ve always felt like a stranger in my own family,” Harry says to Adam in one post-coital scene, as they lie in bed together, their intimacy threaded with an innocent, tentative quality. “A lot of the time, the thing that is actually more provocative isn’t the sex, but the tenderness,” says Scott. “It’s not explicit but it is really intimate, and that draws you in,” says Haigh. “A sex scene can be as important as an argument or meaningful dialogue.”

Scott and Mescal were deeply committed to making those scenes feel true. It was important that there were moments of joy and discovery as relief from the film’s darker corners. And yet, at times, it was hard not to see the funny side. “We had a laugh,” Scott says, recalling the weirdness of shooting the film’s sex scenes. “Jesus, it’s fucking 7:30 in the morning and you’re doing unspeakable things to each other, surrounded by men in three-quarter length trousers.”

Scott recognises that his sexuality is a blessing, something that used to be unimaginable. “There’s this expression ‘my burden has become my gift’”, he says. “I remember when I was 22 reading that and thinking wouldn’t that be amazing? If something that you think is a shameful part of you is actually a bit of you that gives something back?”

A few years ago, amid the still-creeping fog of the pandemic, Scott was alone in Italy filming Ripley. Travel restrictions meant friends were unable to visit him and so he spent his days keeping company with his character, another one that required Scott to delve into the darker parts of his soul. Cut off from his friends and feeling the pressure of people on set becoming ill, the experience started to weigh on him heavily. “I did find that character lonely making,” he says, quietly. “I worked really hard and got quite sick, physically and mentally,” he says, quietly. “It took a big toll on me. So when that was over, it made me think, how do I want to spend my life? I love acting, but I don’t necessarily think you should do it too much.”

Tom Ripley, a con artist consumed by a sinister obsession with handsome socialite Dickie Greenleaf and his beguiling girlfriend, has been played on film before, by Alain Delon and Matt Damon. The new series further examines him as a man looking on at life from the sidelines, spending time in his lonely company as jealousy eats away at him. Scott is used to playing outsiders and oddballs, but Ripley required him to go inwards in a way that felt different. The character, he says, felt totally ideologically opposed to him, and Scott wonders now if he had underestimated how difficult he would find playing someone so marooned from the rest of the world at a time when he felt the same way.

The isolation and pressure of the experience also got to Johnny Flynn, the actor who plays Dickie Greenleaf in the series. Flynn’s lasting memory is of how Scott scooped him up when he arrived in Italy, taking it upon himself to look after everyone. “He got me through it,” Flynn says. “I don’t know how I would have done it without him.”

But when his castmates arrived, Scott didn’t languish in his own darkness, instead throwing himself into looking after his fellow actors, in the theatre tradition of a lead being an almost fatherly figure. If you talk to people who have worked with Scott, that sense of lifting other people up, even in moments of private darkness, comes up again and again. “He’s giving with his love,” says Bella Ramsey, who played Scott’s daughter in Catherine Called Birdy. “He’ll squeeze your hands and nod and really listen to everything you’re saying.”

“Andrew loves people with abandon and loves the characters he’s playing with the kind of ferocity we’d all hope we’d get from our parents,” Lena Dunham, who directed Scott in Catherine Called Birdy, told me. “The tenderness of that love is beamed outwards in every role he ever plays.”

For his friend Paul Mescal, “Andrew is the kind of person who makes you feel better simply by being in their company.”

I get a sense of that side of Scott as we sit for a long time in the darkened bar and he talks in a meandering way, often redirecting to make me laugh or feel at ease. At one point he interrupts himself to say how weird it is to talk about acting. Instead he suggests we talk about the colour of the walls, gesturing at them like a chorus line at an orchestra.

A few days later, we are sitting in another dimly-lit room in the bowels of the theatre, this time watched over by a painting of a young, dead-eyed man sitting backwards on a chair. This afternoon Scott is doing a performance of Vanya which will be filmed for streaming, a recording which Scott assures me he will never watch. Years ago, after playing Hamlet at the Almeida, he sat down to watch it on the BBC only to be so horrified at his delivery of the opening monologue that he had to leave the house until it had finished playing hours later.

Whether or not he can see it, what Scott conjures when he steps on stage is otherworldly. When he did the curtain call for Vanya, I sat and waited for the other actors to join him, my brain not having caught up with it being just one person I had been watching. A kind of magic happens; it feels like he is in communion with the spirit of another person. “I don’t believe in ghosts or God, [but] I do think there’s something holy about this production,” says Stephens. “He populates that stage with ghosts.”

Haigh believes Scott’s singular talent is in part due to his willingness to go small. “He knows how to transmit emotion to an audience so that it doesn’t feel manipulative,” he says. “It’s natural and gentle rather than weighty and serious. I don’t think he’s interested in being a Great Actor and having a large bombastic emotion. He wants it to be small and subtle and real.”

Several of Scott’s friends and colleagues said similar. For Claire Foy, Scott is “one of the greatest of all time.” According to Paul Mescal, Scott has a “special, and if I believed in God I’d say divine, talent for acting.”

Scott himself is spiritual, having been raised Catholic, but he stopped practising when he was a teenager due to the abuse and hypocrisy of the institution. But he is interested in philosophy, talking passionately about hearing Alain de Botton speak about loneliness or Esther Perel’s empathetic writing on relationships. Spirituality, he tells me with those wide, sincere eyes, comes from the old French for breath, the only thing we are guaranteed until we die.

Speaking to his collaborators reminds me of something that Scott said when talking about Fleabag: that despite the series’ dark sense of humour, it is really a story about grief; a reminder how in grief we hold on to the people still with us to help us feel our way through the dark. In the final scene, Scott’s priest chooses his love of God over his love for Fleabag, responding to her “I love you” with the gentle reminder that “It’ll pass.” Scott still believes the words were not dismissive but a statement of faith. “The truth is that it does pass,” he says in that same gentle voice as the priest delivering a sermon. “It may not end forever, but heartbreak is a form of grief, and grief, as they say, is the price you pay for love.”

Story by Olivia Pym

Photography by Petros

Source: gq-magazine.co.uk

Leave a Comment