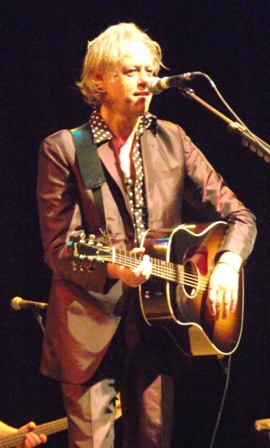

BEING BOB GELDOF

In this exclusive interview with Celtic Life International, Irish musician and activist Bob Geldof reflects on four decades of making a difference

In this exclusive interview with Celtic Life International, Irish musician and activist Bob Geldof reflects on four decades of making a difference

The biopic of Bob Geldof’s life must have already been planned out by a Hollywood producer somewhere. Raised in the backstreets of Dublin, in childhood he had to contend with the death of his mother and merciless bullying, before moving into the adult world and undertaking jobs such as a slaughterhouse worker and a pea canner, as well as being a music journalist for the Canadian urban alternative paper The Georgia Strait in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Wind forward 40 years and the opinionated Irishman is still dealing with the sort of upset that would break lesser men. Of course, in between, he’s arguably done more for developing countries than any other living person, not that the musician, activist and philanthropist would ever agree with such a notion.

Our interview, conducted before the tragic death of Bob’s daughter, Peaches, looks at the potential re-forming of breakthrough band The Boomtown Rats, as well as back on the life experiences that have shaped a complex, unrelenting and unapologetically controversial character.

When bands from days gone by make the decision to re-form, the cynical view is that they’re in it for the money. And as Bob Geldof, the straight-talking, profanity-prone frontman of 70s and 80s Irish punk-rock sensations The Boomtown Rats confirms, that’s just how it is for now, because 27 years after their last official gig, the boys are back.

“Cash is always handy, and some of the guys weren’t as lucky as me,” jokes the 62-year-old, who was born in Dun Laoghaire, Ireland. “But seriously, it’s a really powerful band and I’d forgotten that. I said I’d give it a try because enough time had passed; any silly band politics and resentments, triumphs and failures have deeply receded in me.”

The “silly band politics” may have receded in Geldof, but have they receded in Ireland? During an interview in the 1980s on Ireland’s Late, Late Night Show, Geldof caused an uproar by criticizing Irish politicians and the Catholic church. The interview was so controversial that the Boomtown Rats never played in Ireland again.

But those were the days of punk and the Rats were firmly in the mould. The band had a string of hits between 1977 and 1985, splitting in 1986 after Self Aid, a concert a group of Irish rock stars staged with the aim of raising awareness of unemployment in Ireland. Of course, during this time Geldof had also been busy raising awareness of famine in Africa through Band Aid, as well as co-writing the hugely successful Do They Know It’s Christmas? with Ultravox’s Midge Ure, thus beginning what has become a separate career of philanthropy, building on the ideals he first established with the band.

With songs that touched on political and social themes, including I Don’t Like Mondays and Banana Republic, over six studio albums The Boomtown Rats tapped into a cultural vein they’ve never really left. “It’s so weird that a random group of individuals came together and they make this noise that’s very specific and, as it turns out, very powerful,” Geldof muses.

“You don’t get to be a success by mistake; it’s not an accident. And that noise that we made happened to be the right noise to propel these songs forward. That racket and that drive and, really, a massive amount of anger in sound, worked. But I won’t do nostalgia. It doesn’t interest me in the least. There’s no rear-view mirror in this particular car.”

Indeed, as we chat to the Irish legend, there’s very little to do with his past – especially the extremely difficult time following the tragic passing of his wife, Paula Yates, with whom he had three daughters he has largely had to raise solo. He’s much more about living in the moment, evidenced perhaps by his need to always be busy, working on something, be that musical or charitable projects.

“The truth is I don’t like to take breaks,” he sighs. “To me, boredom is a traitorous friend and it prompts me to do things and remain exhaustively active. It comes from back in the day when I was a kid, when I couldn’t get anything going in Dublin and I was desperate because I did nothing in school.

“Was I working in the abattoir forever? How do I make a go of things? Am I driving heavy equipment forever? I had all these plans to get going but no-one would pitch up the money to help me get started. I was also utterly afraid, living in this genteel poverty, and I wasn’t going back there. It’s awful! I’m not going back there. I’m not asking for the violins,” the popstar says, miming violin playing, “but there was no-one at home and I was cripplingly lonely, I just didn’t know it.”

It’s this fear of being lonely and back in poverty that drives Geldof to escape boredom at all points. “Yeah, it gets me into this depression which puts me back into that place,” he nods. “To stop going there, I stay frantically busy. And by being frantically busy, I have a very interesting life. But I invent my fear every day. If I’m sitting there having my cup of coffee and the phone doesn’t ring, I freak out!”

It’s odd to think of Geldof, who comes across as supremely self-confident, freaking out about anything. “I’m not comfortable; it’s not comfortable being me,” he explains, with the same nervous energy he’s referencing.

“There’s this constant agitation in your head and your stomach. The only thing that quiets it is books. Novels about ideas, not business ideas, but ideas that I like. I underline things in books all the time, making margin notes about nonsense – they’re always a mess by the time I’m done. It’s like they’ve been chewed.”

He goes on, “The Geldof brand is much bigger than the actuality. It comes with all sorts of attributes. There’s the pop-singer part, and the business part and the guy-who-does-all-these-talks part.”

That’s a pretty humble self-appraisal of the brand. Geldof’s commercial success is equally as impressive as the work he’s done in his numerous charitable exploits. While building up his media empire to include the Rats’ back catalogue, TV production companies Ten Alps and (now defunct) Planet 24, along with some canny investment in property that has seen his personal wealth total anywhere between £28million and £1billion, he’s raised vast sums of money for the starving and poverty-stricken, working with his “annoying little brother” Bono on his ONE Campaign, speaking up for fathers’ rights, and much more besides.

But right now, as Geldof points out, it’s all about the music. The Rats are very much back in Boomtown, with a greatest-hits collection and new material, not forgetting the all-important live experience, touring the UK and Ireland and reminding people just why he and they became famous in the first place. However, it’s not as if he could just slip back into the role, even though he’s always been something of a snappy dresser.

“I didn’t know how to be a frontman anymore. I didn’t know how to assume that persona. To sort of somehow visually represent what the songs are saying and the attitude of a collective group of individuals – that I guess would be the job. But I didn’t know how to do that and I was thinking of ways to get back in there. So I hit upon the idea, ‘I’ll wear a snakeskin suit!’

“Bono was watching our Isle of Wight performance online and afterwards, he texted, congratulating me, and I texted back saying, ‘Who knew this snotty arrogant was living under a snakeskin suit?’ He replied back, ‘I knew.’”

Although in the 27-year interim he’s had moderate success with his solo music career, there was a different kind of energy in The Boomtown Rats. Is it difficult trying to recapture that sensation all these years later? “I thought I couldn’t, and apparently I can. They’re huge stages we’re playing and I was convinced I was past it… ‘I’m just not going to be able to do this.’

“I remember fainting at the Marquee gig in Cork. It was just beyond packed – all of Wardour Street had queues of people still trying to get in. We thought wow, the Marquee – Zeppelin, The Stones. But the heat was intense. I have pictures of when I collapse. I’ve got no top on and the sweat is insane; the audience is so close and I just went down. They gave me an energy drink and I just got my breath back and went back on stage!”

He currently splits his time between a home in South London and his Grade II-listed property in Davington, Kent. He’s a loving family man – which makes the circumstances surrounding Peaches’ death all the more painful – though Geldof’s biggest legacy will surely be his tireless philanthropy and charity. Thirty years since Band Aid, he’s still going. “It was never about philanthropy and charity; it was about politics and injustice,” he shrugs. “This poverty that was so hugely unnecessary and against our own self-interest. What I was saying then was it’s an asymmetric world. When you have half the world in poverty and half in wealth, things fall apart and the centre cannot hold.

“Get them talking in the kitchen, round the dining table, in the pub and the café. You won’t get on television talking about Africa and poverty. I will. I’m still trying to do it now, and people are still listening. Ultimately, it’s a fight that will never be won, but it’s certainly a fight worth fighting, so that’s what we’ll do.”

Leave a Comment