Is it possible that a young Pontius Pilate shed a tear as he sailed away from his Scottish birthplace heading for Jerusalem? And how about good old King Arthur? Was that scion of English lore a kilt-wearing Celt? And was the revered, snake-chasing preacher St. Patrick a Haggis eater from Strathclyde?

All could be so if you choose to believe the legends and stories claiming these three were all Scots lads born and bred.

Scratch the soil of Scotland and you are disturbing countless layers of history, of things known and unknown, of fact, of conjecture, and of myth. Many tales have come swirling down through the mist covered hills and glens – stories of heroes, of brave deeds, of great adventures. For a Celt, it is not a big stretch of the imagination to accept some of these narratives as ‘our own’.

If we believe the adage that legends and myths have some sort of basis in reality, then we must assume that there might be something to these ‘local legends’ – especially for Arthur and Patrick.

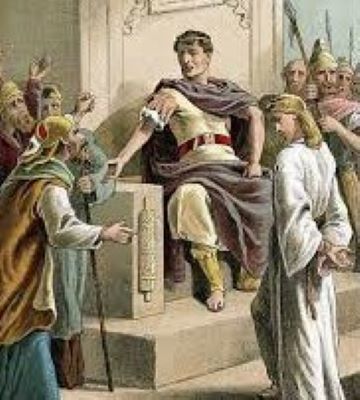

But Pilate? This man’s encounter with Jesus is the only real focus we have on his life which make his beginnings – and his end – almost irrelevant. One could ask why any country would want to claim him as one of their favourite sons?

Despite the lack of any real evidence, however, the legends persist. Some claim that Pilate was born in Fortingall, Arthur was from Govan and/or the Borders, while St. Patrick’s hometown is Old Kilpatrick.

Let’s start with Pilate. Local lore has it that about 10 B.C. a baby was born to a Roman official and his Scots wife living in a Roman trading fort near Fortingall in Perthshire. This child would grow up, journey with his father to Rome, eventually becoming procurator of Judea.

Fortingall is a tiny village not far from Aberfeldy. A sacred yew tree, thousands of years old, still grows beside a tiny church said to have been built on a Druidic site. Across the road is a plague cemetery, and nearby are sites of standing stones. A little further up the road is Dun Gael, a ring fort of the Iron Age, and a new archeological dig near the cemetery is currently uncovering a large Pictish site. Not far away is a mound known as the ‘praetorium’ – where, in 1934, a Roman amphora was dug up and now sits in a museum in Stirling. This is a place made for legends, and while there is no direct proof Pilate was born here, Fortingall has a rich history that goes back 5,000 years.

One piece of ‘evidence’ pertaining to Pilate is an Elizabethan manuscript. The Holinshed Chronicles from 1577 claims that Pilate’s Roman father was sent to the area thanks to King Metallanus, a Pict from Dun Gael. Metallanus is a Romanized name indicating the King’s wealth in Iron and metals – something the Romans would have been most interested in acquiring.

And if you think it is only locals who believe the legend, have a look at Britain’s oldest regiment, The Royal Scots, whose nickname is ‘Pontius Pilate’s Bodyguard’ – claiming that status back in 1635 during a dispute with a French regiment about which one was older.

What about Arthur? We all know the tragic story; of Camelot, of Lancelot, of Guinevere and the Round Table – all somewhat doubtful. But really, that’s about it – so little is known of Arthur that many historians don’t believe there was such a person much less that he was a Scot. Nobody has ever found Excalibur or any other physical proof. But If there was no such person why are there more than 2,000 names associated with him in Britain? And why did four regional Kings name their sons Arthur toward the end of the sixth century, just decades after this imaginary Arthur’s apparent death in 517?

Are the Scots trying to cash in on the legends or is there a bit more?

Let us take a closer look. In 1120, a chronicler, Lambert de St. Omer of Brittany makes a statement that ‘There is a palace of Arthur the Soldier, in Britain, in the land of the Picts.” But wait – there is more; around 600, an epic poem – ‘The Gododdin’ – about an old Celtic/British tribe with strongholds in East Lothian, mentions the strength and courage of Arthur, a War Leader of that tribe.

Coupled with many local Scots place names relating to battles and locations all derived from the ancient Welsh language, it becomes obvious that Arthur had a large fan base north of the border. And what about that big hill in Edinburgh known as Arthur’s Seat?

When the Romans left Britain in 410 the Picts, the Irish and the Saxons all attacked the former Roman province seeking plunder and new land. The only major fighting force to oppose the invaders sprang up in the Borders led by the Gododdin, and under their leader they continued to fight for more than 50 years.

Alistair Moffat, a Scottish writer, claims this leader was Arthur and that his cavalry headquarters was based at Roxborugh, previously named Marchidin, which means Cavalry Fort in the old Celtic language. It is Moffat who researched so many of the place names in the Borders affiliated with this clan. Moffat contends that Arthur headed south to help ward-off attacks from the Irish and the Saxons.

Another historian, Andrew Breeze, a professor in Spain, has Arthur operating from Strathclyde on the country’s east coast. This Arthur, says Breeze, came from Govan, now part of Glasgow and just 40 miles from Moffat’s Arthur. Same person perhaps?

Bragging rights between Glasgow and Edinburgh aside, the invaders won the battle and the Celtic Britons were pushed back to what is today Wales, where they retained the old stories which gave rise to the belief that Arthur was from Wales.

Meanwhile, if you are heading towards Loch Lomond from Glasgow you will cross over the Erskine Bridge, within waving distance of the birthplace of St. Patrick – or so say the old legends and letters, including some by Patrick himself.

His hometown, Bannavem Taburniae, was thought to be a Romano/Celtic settlement at the eastern end of the old Antonine Wall near the present Old Kilpatrick. As a youth, Patrick was waylaid by a gang of pirates and sold as a slave in Ireland where he was a shepherd before escaping, returning home to become a priest before going back to Ireland.

Along with Patrick’s letters giving evidence of his familiarity with Strathclyde and Dumbarton, and hints about his birth and parents, other clues to his birthplace include the Oxford Dictionary of Saints. In addition, so many sites are associated with Patrick in this corner of Scotland that it would take a brave soul to place him somewhere else.

Fact or fancy, myths or kernels of truth? We don’t know. But as time went on the legends of Arthur and Patrick grew and expanded to fill our needs for great and heroic figures. Nobody, however, really wants to be too closely associated with Pilate – except, perhaps, The Royal Scots – but even so, the stories of his Scottish birth remain.

And though it is quite possible that none of the three were born in Scotland, evidence and local lore will continue to be collected and it is unlikely that Fortingall, the Borders or Old Kilpatrick will give up their claims anytime soon.

Leave a Comment