Kenneth Branagh has never understood himself as plainly as he did while growing up in Northern Ireland. His relationship to the world was “completely clear and effortless,” the filmmaker says — the product of childhood naivete and the comforts of a close-knit neighborhood.

That dynamic changed suddenly in 1969 when rioting broke out near his home in Belfast early on in the Troubles, a period of violence between Irish nationalists and unionists that lasted from the late 1960s through 1998. On the cusp of reaching double-digits in age, Branagh was whisked away to England — a move made in search of a safer life but one that sent his secure sense of being into a tailspin.

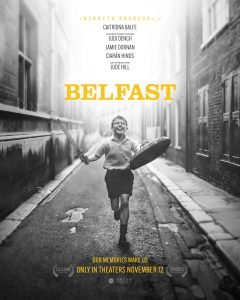

Decades later, Branagh, 60, is finally grappling head on with the weighty emotions behind his working-class family’s decision to leave familiarity behind. In theaters Friday, his film “Belfast,” a fictionalized glimpse into their final year living in Northern Ireland, begins with a mob storming through their once-idyllic street. From there, it focuses on a boy named Buddy as he tries to make sense of his rapidly changing environment.

Branagh says his parents rarely discussed the trauma of displacement, as though they were “committed to making good on the sacrifice.” The five-time Academy Award nominee has been directing for years but admits he hadn’t previously been in the right mind-set to dive into this particular story, either. Adapting Shakespearean plays and helming blockbuster movies such as “Thor” and “Murder on the Orient Express” can be transforming work, but it doesn’t necessarily prepare someone for the massive undertaking of processing their own life through film. It wasn’t until Branagh was staring into the silence of the early pandemic that he sat down to write about the first time his world turned upside down.

“Part of the Belfast condition would be that you never show off,” he says. “You never have ideas above your station. You do not think you’re better than anybody else. I couldn’t tell the story until I felt there was some recognition in it, that it wasn’t some navel-gazing act of my own.”

Largely told from a child’s perspective, “Belfast” is a much lighter watch than one might expect of a film set during the Troubles. Nine-year-old Buddy (played by newcomer Jude Hill) guides its vision of the city, sometimes literally — a selection of shots, including the ridiculous yet recognizable sight of a preacher yelling fire and brimstone at flinching children, were filmed from the boy’s eye level.

Buddy idolizes his parents, simply referred to throughout “Belfast” as Pa and Ma. He regards his father as though he were one of the movie stars they watch on-screen together at the local theater, actor Jamie Dornan portraying the industrious character with the mysterious air of a man who spends a considerable amount of time away from home, working construction in England to provide for his family. Caitríona Balfe plays Ma with a dose of glamour, also lending a stubborn streak to the dependable matriarch.

“It felt as though there was a kind of license, a freedom and a certain playfulness,” Branagh says of his decision to shape elements of the story around Buddy’s version of reality. A good portion of the runtime consists of the boy’s day-to-day interactions with his parents and grandparents (Judi Dench and Ciarán Hinds), as well as his endearing pursuit of a classmate he has a crush on.

“Belfast” has earned stylistic comparisons to Alfonso Cuarón’s “Roma,” another project shot in black and white that revisits the filmmaker’s upbringing. But the new release might also recall elements of “Jojo Rabbit,” Taika Waititi’s World War II satire about a German boy who discovers his mother has been hiding a Jewish teenager in their attic. Branagh and Waititi highlight the absurdities of “us and them” mentalities by filtering politics through children’s lenses, the protagonists’ confusion interrogating why the divisive ways of being make sense to many of the adults around them.

While Branagh overall opted for a more depoliticized approach to storytelling — he describes “Belfast” as a mood piece, floating from each childhood memory to the next — the film still makes it clear there are sides to the conflict at hand. Pa faces increasing pressure from fellow Protestants to turn against his Catholic neighbors, a dichotomy Buddy struggles to comprehend within his own life.

Among the most memorable scenes is one where Buddy chats with his cousin, Moira (Lara McDonnell), about how to differentiate between Protestants and Catholics based on their names alone. Names like Patrick are easy enough, they decide, but what about those that cross over? Buddy becomes flustered as the task grows more complicated, unsure what to make of his inability to tell the difference.

“It’s his version of what’s later explicitly put in a phrase that is very familiar to us these days — you’re either with us or you’re against us,” Branagh says. “The absurdity of that conversation [with Moira] is to underline how difficult it is to grow up with strong lines drawn.”

After Branagh moved to England, to a town about 40 miles west of London, he tried to disappear. He worked to “rub the edges off” his accent, he says, which in conjunction with later attending drama school and pursuing a career in acting led him to speak with the English accent he has today.

But no matter how English he became, Branagh never shed his connection to his Irish heritage. It’s that “cliched, glib-sounding phrase,” he says. “You can’t take Belfast out of the boy.” His parents — who weren’t too keen on “keeping up with the Joneses,” he adds — chose to raise their three children as they would have back home. The mentality shaped Branagh’s approach to art; he notes that the gallows humor scattered throughout his latest film is “very much a part of Belfast coping mechanisms.”

But no matter how English he became, Branagh never shed his connection to his Irish heritage. It’s that “cliched, glib-sounding phrase,” he says. “You can’t take Belfast out of the boy.” His parents — who weren’t too keen on “keeping up with the Joneses,” he adds — chose to raise their three children as they would have back home. The mentality shaped Branagh’s approach to art; he notes that the gallows humor scattered throughout his latest film is “very much a part of Belfast coping mechanisms.”

Branagh’s childhood also encouraged him to act on his learned belief that everyone belongs on an even playing field, opening doors to him he never thought possible. At one point in his life, the filmmaker says, performing Shakespeare “would have been like going to the moon.” He has since directed and starred in several on-screen adaptations of the playwright’s work — including 1989′s “Henry V,” which earned him his first two Oscar nominations — and once even played the bard himself.

“For me, it was very important that it was available to everybody,” he recalls of his adaptations. “I was like them, not needing to join some elite club and closing doors behind me. Quite the opposite. I wanted to bang on the doors, open them up and say, ‘We can enjoy it as well,’ you know?”

Much art has been produced about the Troubles, Branagh says, the subject “so immense and so complex that it can be hard for any film to do it justice.” He didn’t try to encompass it all, especially because his family experienced only the start of the violence. Framing “Belfast” around Buddy’s experiences was Branagh’s way of opening the story up to a broader audience, one that could not only relate to his childhood innocence but also the emotions stirred up by uncertain periods in life.

“It’s his version of what’s later explicitly put in a phrase that is very familiar to us these days — you’re either with us or you’re against us,” Branagh says. “The absurdity of that conversation [with Moira] is to underline how difficult it is to grow up with strong lines drawn.”

Story by Sonia Rao / Source; WashingtonPost.com

Leave a Comment