After the Roman invasion of Britain in AD43, one man, Caratacus, evaded capture for nine years, leading the Welsh tribes against the might of the legions. This is the second of three articles about Celtic leaders who defied the Roman empire, and my journey to the places where they lived and fought. It begins in the mountains of mid-Wales and ends in Rome, where a twist in the story has preserved his memory for 2000 years.

Iron Age Britons spoke Celtic languages from the same family as modern Welsh, so we may consider them ‘Celts’, although no-one called them that at the time. There is some fragmentary evidence of writing from that time, but our only written sources for these events come from Roman writers, whose view was obviously distorted.

Unlike some other figures from ancient history, we know that Caratacus definitely existed because coins were minted bearing his name. Most of what we know about him comes from the Roman writer Tacitus, who seems more reliable than most ancient sources, although he was also a politician with an agenda of his own.

Caratacus was the son of a dynasty which was expanding its territory across Southern England. When he conquered the Atrobates, in modern-day Hampshire, their deposed leader fled to Rome, seeking assistance. This gave the Romans a pretext to invade. At the Battle of Medway in AD43 they defeated the army of Caratacus, who escaped to the West.

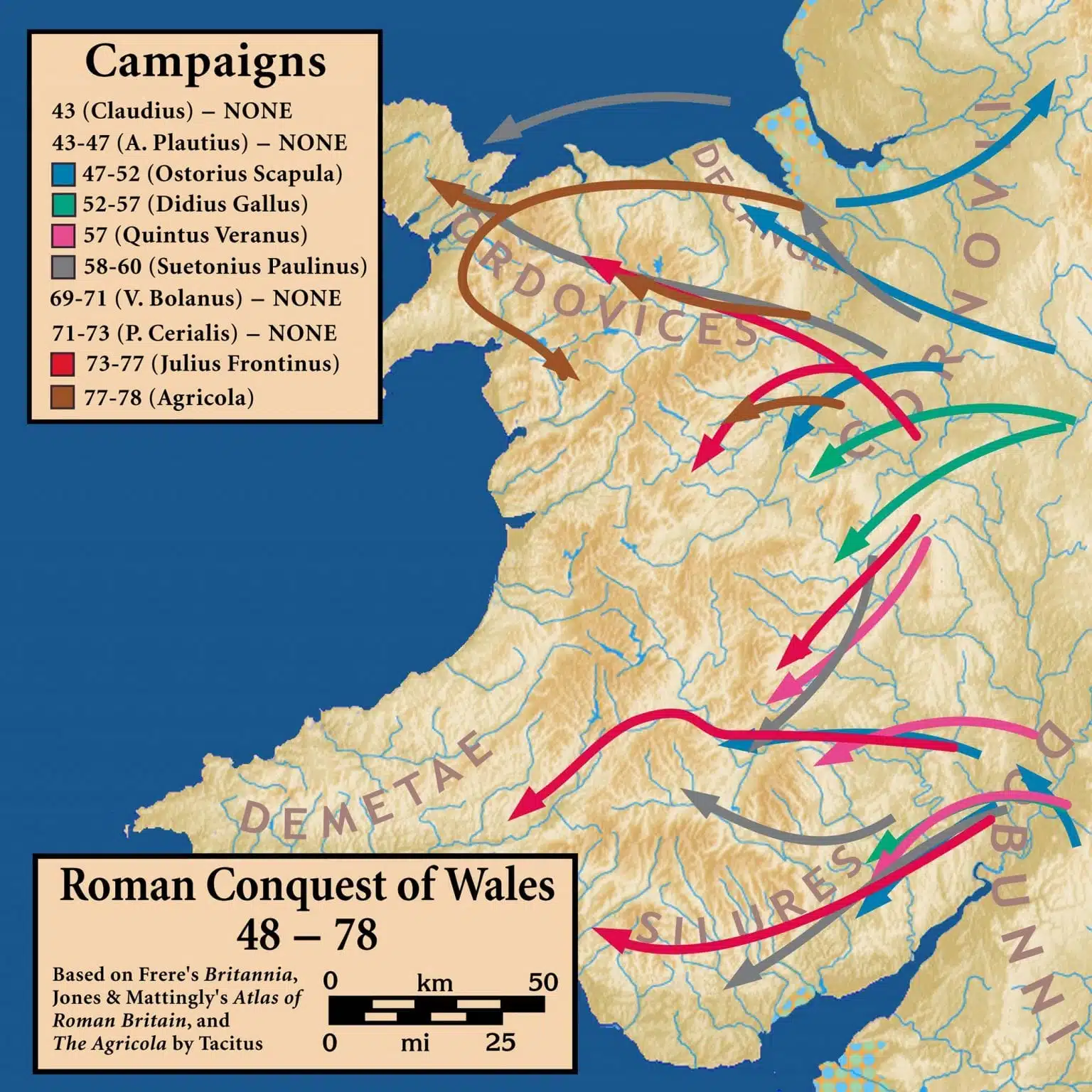

Over the following years, he led two Welsh tribes in guerrilla warfare against Roman-occupied territory. In AD49 the Roman governor, Scapula, decided to attack Caratacus and subdue the Welsh tribes. After years of hit-and-run tactics, the scene was set for a full-scale battle. By this point, Tacitus tells us, Caratacus had “transferred the scene of the conflict to the territory of the Ordovices” who ruled most of North and mid-Wales. He chose a site where “advance and retreat alike would be difficult for our men and comparatively easy for his own”. Over the years many places have claimed the battle site of Caer Caradog (Caratacus in Welsh) but the sites most favoured by experts such as Graham Webster (author of Rome Against Caratacus) lie beside the River Severn in mid-Wales.

In the years following the battle, the Romans built a major fort by the Severn at Caersws in the heart of Ordovice territory. South of the village stands the Iron Age hillfort of Cefn Carnedd, where a slingshot and evidence of past burning were found in 2007. This seems the most likely site.

In the years following the battle, the Romans built a major fort by the Severn at Caersws in the heart of Ordovice territory. South of the village stands the Iron Age hillfort of Cefn Carnedd, where a slingshot and evidence of past burning were found in 2007. This seems the most likely site.

I started planning a visit last autumn but hit a problem: the maps were showing no access to the top of the hill. After searching online, I found someone who might be able to help me. We arranged to meet by Caersws railway station a few days later.

By British standards mid-Wales is sparsely populated. As there wasn’t much accommodation in Caersws I stayed in the nearest town, Newtown, upstream from Caersws along the River Severn, with a walking trail between them. The Severn Way is one of many long-distance footpaths in Britain – all reasonably well signposted – although you still need a map or a mapping app as well.

From Newtown to Caersws was 15km, but it felt longer, taking me nearly five hours. From Newtown it climbs the hills which overlook the Severn valley. The ground was hard and some of the streams had dried up, but the hills and fields were still lusciously green. I spotted ravens, red kites, and a peregrine falcon along the way.

The site of the first Roman fort, built in the early days of their occupation, lies next to the path just before you enter Caersws. I walked past it without realizing at first, until I saw an information board, which explained that it is now only visible from the air. Earthworks from a later fort, which grew to a significant settlement, can still be seen near the railway station, where I met local guide Helen Menhinick.

Menhinick runs Bryn Walking, offering guided walks across Wales and overseas. When she started the business, she thought she would be doing most of her work locally but, she said: “nobody comes to mid-Wales. It’s beautiful; it’s understated, and it’s empty of tourists.”

I followed her along the Severn Way, where it skirts the bottom of Cefn Carnedd, through some woods towards a farm, where a small noticeboard indicates a ‘permitted footpath’, agreed with the landowner but not shown on the maps. From there we climbed quite steeply towards the summit. The sheep, who usually have the hill to themselves, scattered in fear. Like other Iron Age hillforts that I have visited, the site was evidently chosen for its defensible plateau and 360-degree views across the surrounding countryside. The earthwork defences, which would have supported wooden palisades, are still intact.

The views towards the river are spectacular. Tacitus writes how the river crossing and the steep slope of the hill daunted the Roman general, but his troops “demanded battle.” They crossed unopposed until they reached the defences where they initially “suffered more wounds and more casualties” than the Britons, but once they had broken through, the battle turned to a rout. Caratacus’ wife and daughter were captured, but Caratacus – a great master of escape, eluded their grasp once again, though not for long. He fled to the neighbouring territory of the Brigantes, whose Queen Cartimandua, a Roman ally, handed him over to the Romans.

Over the following years the Romans conquered all of Wales and we might have heard no more of Caratacus, but there was a twist in this tale, one which stuck in my memory when I read it as a child. One day, I thought, I will go to Rome to see where it all happened. It took me fifty years to get round to it but, on a recent sunny afternoon I finally arrived at Rome’s Termini station.

My first impressions of the city were bewildering: the traffic is pure chaos, and many of the pedestrian crossings are just painted stripes where cars and scooters drive at you from all angles. They might slow down or swerve round you, but no-one stops.

My first impressions of the city were bewildering: the traffic is pure chaos, and many of the pedestrian crossings are just painted stripes where cars and scooters drive at you from all angles. They might slow down or swerve round you, but no-one stops.

Ancient and historic buildings surround you – far too many to explore in one visit. I tried to imagine how Caratacus might have felt arriving in a city so much larger than anything he would have known back home.

The next day I walked the route that the triumphal procession would have followed with Caratacus and the other captives on the way to their public execution. The starting point where the troops used to gather, the Circus Flaminius, no longer exists. The site is now in the Jewish quarter, lined with kosher restaurants behind the great synagogue.

The Roman empire lasted nearly 400 years after the invasion of Britain. Many of the remains seen today were built long after Caratacus, but he would have seen the temples of Jupiter and Juno, on the edge of the Jewish quarter, and the Foro Boario, with its circular temple, where four people, two of them Celts, were buried alive to placate the gods. He would have walked, as I did, along the Circo Massimo, a wide-open space with grassy banks on either side, overlooked by the imperial palace on top of the Palatine Hill. At the end of the Circo I turned left towards the Arch of Constantine and Rome’s most famous building, the Colosseum.

The Colosseum was built shortly after Caratacus’ arrival, but a guided tour gives a fascinating insight into Roman culture. Like many imperial powers, the Romans tried to justify their imperialism by contrasting their civilization with the barbarism of the peoples they conquered. A visit to the Colosseum helps put that in context. The main attraction, our guide explained, came at lunchtime, when criminals, political prisoners, and runaway slaves were led into the arena followed by hungry beasts who devoured them. Whereas some of the conquered peoples, including the Celts, occasionally practised human sacrifice for religious reasons, ‘Damnation to Beasts’ was the ancient equivalent of reality TV, with the added benefit of free pet food.

The Forum site lies next to the Colosseum. Inside, I followed the Via Sacra, the road still paved with the original stones, which leads through the site towards the Capitoline Hill. The complex is full of ancient buildings and remains, of varying dates. I would spend the rest of the day there, but for now I was on a mission to follow the footsteps of this king whose fate was becoming an obsession. I walked past temples and marketplaces, past the Forum itself until the path turned left to climb the hill. Towards the top, I was disappointed to find a chain cordoning off the exit. I was very close to my destination, but the last part would have to wait.

The following morning, I walked to the top of the hill, where I had an appointment in the Capitoline Museum. Curator Eloisa Dodero took me behind the museum to show me where the procession would have climbed towards the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, whose foundation walls now lie inside the museum. In front of the temple stood the tribunal where the emperor would decide the fate of the captives.

Back inside, she showed me a marble relief depicting an emperor’s tribunal and a fragment of the triumphal arch built to celebrate Claudius’s conquest of Britain. Half the words are missing, but it clearly mentions the surrender of the British kings.

An underground passage connects the main museum to the ‘new palace’, which houses some of the ancient world’s most impressive sculptures, including one I have wanted to see for many years. The Dying Gaul is a masterpiece of imperial propaganda tinged with artistic empathy. The naked warrior is identified as a Celt by a torque around his neck. His sword lies broken beside him. I bent forward to see his face, turned towards death with fortitude. A moment later a small boy ran into the room and stared in astonishment at the sight of a grown man crying in front of a sculpture.

I needed some fresh air and walked back out to the viewpoint overlooking the Forum, where Emperor Claudius, unusually, allowed Caratacus to plead for his life. This was the twist I remembered from my childhood. While those around him cowered in fear, according to Tacitus, he stood firmly to deliver the following speech:

“Had my moderation in prosperity been equal to my noble birth and fortune, I should have entered this city as your friend rather than as your captive; and you would not have disdained to receive, under a treaty of peace, a king descended from illustrious ancestors and ruling many nations. My present lot is as glorious to you as it is degrading to myself. I had men and horses, arms, and wealth. What wonder if I parted with them reluctantly? If you Romans choose to lord it over the world, does it follow that the world is to accept slavery? Were I to have been at once delivered up as a prisoner, neither my fall nor your triumph would have become famous. My punishment would be followed by oblivion, whereas, if you save my life, I shall be an everlasting memorial of your clemency.”

For reasons of realpolitik, or perhaps a streak of genuine humanity, Claudius decided to spare him and his family, who lived the rest of their lives somewhere in Italy.

For the rest of my stay I would marvel, as Caratacus did, at the opulence of Rome’s buildings and monuments. Standing under the gilded dome of St Peter’s Cathedral, I recalled the last words attributed to him, as he walked through the city after his liberation: “and can you, then, who have such possessions and so many of them, covet our poor huts.”

Story by Steve Melia

Leave a Comment