Scotch whisky has been around for a long time in Scotland. A very, very long time – it can all be traced back to a 15th-century friar making spirits for the king.

“The abridged version – because it goes all the way back to 1494 – is that, in the exchequer rolls, the king’s tax records of that year, there is one line in Latin,” says Drew McKenzie Smith, founder and Managing Director of Lindores Abbey Distillery, in Fife, Scotland. “Translated, it says, ‘to Friar John Cor, eight bolls of malt wherewith to make aqua vitae for the king.’ Eight bolls of malt was actually quite a significant amount.”

According to McKenzie Smith, Friar John was likely using these bolls of malt in a relatively humble distilling set-up to brew aqua vitae – ‘water of life’ in Latin – the precursor to modern-day whisky.

“There was probably spirit being distilled before that, but it is the earliest record of it,” he shares via Zoom. “To say there was a distillery is Scotland 500 years ago is maybe being…poetic. But there was whisky – or aqua vitae – production here.”

With half a millennium of history behind it, the image of Scotch whisky today is now cemented in the minds of spirit aficionados the world over. That is both an incredible advantage to the whisky market, but also – especially if you are a new distiller on the loch – something of a hurdle.

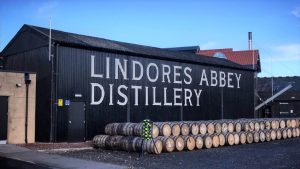

Despite its historic connection to Friar John, Lindores Abbey Distillery is actually rather new on the Scotch whisky scene – the distillery only opened its doors in 2017. And, as McKenzie Smith explains, that heritage was vital to getting those doors opened at all.

“I wouldn’t have been able to raise the finance if it hadn’t been for that one little line in the exchequer rolls all those years ago. To be fair, there are lots of new distilleries cropping up all over the place, some of them with no history. That doesn’t make them bad distilleries, a lot of them will be producing good whisky. But it did make my job easier, the fact that we had this USP – unique selling point. When I went out with the begging bowl, it wasn’t as hard as it might have been. This is quite a substantial investment, as you can imagine.”

A Scotch whisky distillery is indeed a significant venture, perhaps more so than other spirits. That is due in part to the staunch regulations that must be adhered to in order for a product to be designated as “Scotch whisky.” Not only must it be brewed on Scottish land, but the approved ingredients (water, malted barley, and other whole grains) must be fermented only by adding yeast. Perhaps most significantly, it must be allowed to age for a minimum of three years before a single drop can be sold.

“The big issue I had was explaining to people that the whisky business is quite hard,” says McKenzie Smith. “I am trying to say to people, ‘invest in my business, but – by the way – there is huge up-front expenses, you can’t sell anything for three years and a day,’ and you can see people think, ‘well that doesn’t sound like a great business model you have.’

“With whisky, you have to be looking at the mid-to-long-term.”

Truth be told, that is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the knowledge of not just the production, but also the history, one needs to know in order to excel in the Scotch whisky industry. Even Kirsty McKerrow, whose father was once CEO of Glenmorangie, and who attended her first whisky tasting at the tender age of eight, didn’t know it all just from osmosis alone.

“I think we might have to reword that to ‘whisky-nosing,’ otherwise we might get our parents in trouble,” she laughs via Zoom with Celtic Life International. “He would line samples up in the dining room and ask us – me, my brother, and my sister – to just go down and nose them. I think it was just a fun way of involving us in whisky.”

Despite that early engagement, McKerrow didn’t initially join the family business, instead working as a paramedic for 12 years in London, before moving to Sweden. Her paramedic credentials didn’t transfer, so she set up tastings, and eventually took up a new career as the Nordic brand ambassador for Glenmorangie. It was during that stint that she realized how hard it was for whisky professionals and enthusiasts to learn all there was to learn about the spirit.

“The more you learn, the more you realize the less you know, and the more you want to learn,” she muses. “The production process, the cask treatment, they are all very key factors in the flavour profile. I wanted to learn more and more about the charring, or reflux, whatever it was. And there was really nothing to teach all that on the market at that time. There was this huge credibility gap for brand ambassadors, serious whisky enthusiasts, people who run whisky clubs, or who wanted to take their passion a bit further.”

McKerrow decided to fill that gap herself and launched the Edinburgh Whisky Academy in 2015. Courses range from £25 modules on identifying flavour notes and scent bouquets, all the way up to multi-module, professionally certified diplomas for those wishing to relaunch or open their own distilleries.

“As a brand ambassador, I said, ‘this is exactly what I want to know in order to do my job really well.’”

As noted earlier, starting up something brand-new can be challenging; it is a tough market to find your niche in – one needs to offer something to help them stand out, while also not rocking the boat too much, according to Lindores Abbey’s distillery manager, Gary Haggart.

As noted earlier, starting up something brand-new can be challenging; it is a tough market to find your niche in – one needs to offer something to help them stand out, while also not rocking the boat too much, according to Lindores Abbey’s distillery manager, Gary Haggart.

“Even though the industry is innovating, there are still a lot of core values cemented in that you have to adhere to; you have to respect what has gone on in the past. It is just three ingredients – yeast, malt, and water. That’s it. Are we just doing innovation for innovation’s sake? Just to be different? I do think the industry is going to stop trying to reinvent itself all the time and just stabilize. Let’s just make good quality whisky.”

That said, it’s not like there is no room in the industry for innovation, or room to play alongside other spirits, explains Ian McKerrow, Kirsty’s brother and the head of finance and international development for the Edinburgh Whisky Academy.

“Within the overall picture, there are parts where there is innovation going on,” he elaborates. “I would highlight grain whisky, in particular. Blended malts, I think, is becoming a lot more popular, because that is much more suitable for cocktails. Whisky cocktails are a really good way of introducing people into whisky.”

Stewart Dick – a team leader with Tomatin Distillery, a popular whisky TikTok-er, and a graduate of the EWA – echoes the sentiment.

“I make cocktails, and I don’t care what whisky ‘is.’ If I think it is going to add to the flavour, I will add it.”

More than just getting crazy with cocktails, Dick believes that the spirits market has plenty of room for more than those who prefer their Scotch the old-fashioned way.

“I am all for going crazy – I like messing about with my whisky,” he beams, while adding that the traditional way Scotch is marketed doesn’t connect with every demographic. “In terms of what customers are looking for, I think that is relevant. The one bit of baggage that Scotch has is that kind of cobwebby, dusty image. This ain’t your granddad’s Scotch. That’s not what we are selling nowadays.”

For one, while it is not technically “Scotch,” lots of places outside of Scotland make whisky. Ian McKerrow believes that there is opportunity for those batches to sell themselves not on how similar they are to Scotch, but rather on what makes them different.

“We’ve got Irish whiskey undergoing a sort of renaissance, and lots of others. Penderyn in Wales is another really good whisky. There is whisky production in England. Taiwan has very good whisky. Japanese whisky has obviously gone through the roof in recent years. From a consumer perspective, you are getting a huge variety.”

David Roussier, general manager of the Armorik Distillery in Brittany, France, says that his company’s claim to fame is the unique French botanicals used to make their whisky.

“It was built in Lannion, to produce fruit and plant liquors for local distribution,” he explains via email. “We are a certified Breton Single Malt Whisky – it means that the Breton origin makes a difference in terms of water used and climate for maturation. A lot of new distilleries, new whiskies to try, and a lot of potential for Armorik. All this booming activity around whisky forces us to remain innovative and to work hard to stay at the top of French whisky world.”

Other spirits, not traditionally associated with Scotch-makers or the Celtic Nations, are also starting to rise in prominence, if mostly for a very pragmatic reason.

“New distilleries in Scotland are starting to produce gin, because you make gin today, you sell it tomorrow,” says Dick. “They’ve got to get some cash flow in.”

As a result, Scottish and Irish gin is becoming another staple spirit of the region. Dick presumes that they will never achieve the same provenance as Scotch, but that also leaves their producers open to being more flexible and experimental with their flavours.

“These guys up at North Point, and I think they are a great example of this as their focus is on producing something unique, something interesting, something full of flavour.

“There is way more experimentation going on. People are more focused on the quality of ingredients, and the quality of what they produce. That is a general thing, and that is true of the whisky industry, as well. That is where I think the spirits industry is going in Scotland.”

That is the path Lindores Abbey is carving out to their niche in the market. Rather than looking to the future to see what wild new things can be done to the spirit, they are looking back along the drink’s evolutionary tree, and seeing where they can branch off in other directions.

For one, rather than keeping the lights on with gin, they have turned to Friar John’s instigating brew and have brought back whisky’s distant ancestor, aqua vitae.

“Making a gin would have kept my bank manager very happy,” McKenzie Smith says while explaining the decision to make aqua vitae instead. “If we had done a pink gin, that would have made her even happier – but we would have then, I think, sold ourselves short. It is a new make spirit, so it is not a neutral grain spirit. Then it is infused with some plants that grow in the abbey, like Sweet Sicily. We are selling it as a sort of pre-whisky drink. We did that instead of the gin, and that has paid some of the bills.”

They have also partnered with Crafty Maltsters to highlight the very barley that whisky is made from. Together, they have just milled their first batch of organic malt for a new line of organic Scotch.

They have also partnered with Crafty Maltsters to highlight the very barley that whisky is made from. Together, they have just milled their first batch of organic malt for a new line of organic Scotch.

“Lindores is the closest distillery to us,” says Alison Milne, who turned a sixth-generation barley farm into Crafty Maltsters less than two years ago, selling their malt to brewers and distillers with the goal of highlighting the barley as a top-quality ingredient to boast about.

“Whilst we work with brewers and distillers, obviously, we were really keen to establish a relationship with Lindores, because so much of what we do is about the provenance of the barley and the heritage story.”

Lindores and Crafty Maltsters are only a few kilometres apart, and Haggart says that highlighting a sustainable production line is another way Scotch is best suited to innovate.

“In the industry, there is a big part to play in sustainability and making sure that we are doing the right thing,” he expounds, adding that the barley Milne farms is of an older strain than the high-yield ones that bigger distilleries tend to use today. “So, to keep all that within a fairly small circle, and really close the loop down, is also the right thing to be doing.”

The organic route also tastes great, according to Haggart. And that’s the one thing on which a good Scotch should never waver.

“It is very sweet, but not a sickly sweet. It is a tropical sweet, which is one of the things we were really looking for. But I don’t want to give too much away. People are just going to have to wait and see what comes out of this unique first spirit.”

Leave a Comment