The Gaelic word for month is Mios, and like most European languages it relates to the disk shape of the moon; which waxes and wanes across the heavens every 28 days or so. This was very much part of the great clock by which the farming societies of early Scotland operated; a year punctuated by celestial events such as solstices and equinoxes by which seasons could be predicted, and the right time calculated for things like harvesting. For thousands of years, dating back to the Neolithic, this was the only necessary calendar for the vast majority of the population; and much of this ideology remains encapsulated in the old traditions and our interpretation of the year.

Gaelic is a wonderfully descriptive language, an ancient tongue firmly rooted in the agrarian world of our forebears; it is not a language of commerce or town, but of farm and hearth, of natural observation with a deep sense of being part of the environment. As such, the breakdown of the year doesn’t necessarily correspond with the familiar 30 days or so per month of the modern Gregorian calendar; but splits the year up into periods that are underpinned by the cycle of the Mios. The Gaelic for ‘year’ is Bliadhna, which is a word that derives from a sense of ‘separation of time’; and the key segmentation of time for the Gaels was, and to a certain extent still is the seasons.

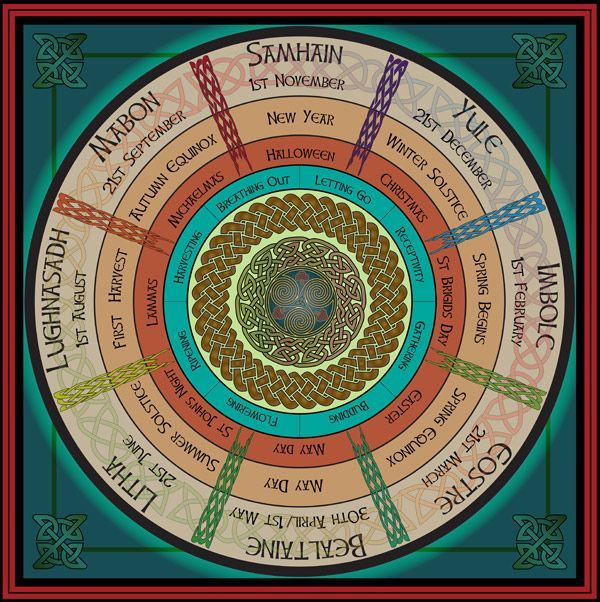

The Gaelic year began in November following the festival of An Samhain (which evolved into Halloween); and it ushers in the first of the new seasons: winter. The cold was considered necessary to cleanse the land and prepare it for the new bountiful year ahead. In Gaelic it is rendered An Geamhrachd, coming from an early Celtic term for cold, which in turn comes from an even more ancient linguistic source for ‘stiff and rigid’, describing the frosty ground. Within An Geamhrachd there are the three ‘months’ of An Dubhlachd, Am Faoilleach and An Gearran, meaning – the Dark Days, the Wolf Month and the Cutting or Gelding Month respectively.

The ‘dark days’ certainly capture the essence of December with its long, long nights – always more bearable with a couple of single malts of course. The ‘wolf month’ takes us back to the harsh and hungry weeks of January and early February when the wolves came down from the hills to scavenge – it is a common theme in many traditional winter tales across northern Europe. The gelding or castration of the cattle took place in late February so to let the wounds heal better, and without the nuisance of flies. As you can see each month has a significant theme, folk memory or important task on the farm; and this is repeated throughout the year as it unfolds.

When spring finally comes it usually arrives on the back of storms, rain and fierce winds. This is why it is so associated across Europe with the Roman God of War, Mars – and in the Highlands it was no different. March is Am Màrt, which comes from the same root. April is called the ‘Pudding Month’, An Giblean. The reason for this is more obscure, but my sources tell me that with summer just around the corner the fats, oatmeal and other stocks that saw the village through the winter were gathered together for a great feast, and that pudding (in the traditional sense) was the best way of cooking the leftovers. Spring is known as An t-Earrach, and reflects the sun rising more towards the east and the end of the cold days.

Summer is ushered in at the start of May with the great festival of the Beltane, and takes its name An Samhradh, from the very earliest Indo-European language root for the sun – samh, meaning heat. The English word ‘sun’ originates in the same way. It probably had quasi-religious connotations originally. June in Gaelic is An t-Ogmhìos, which probably means the ‘youthful month, or the month of the young’ This maybe the month when the younger beasts, went to the slaughter; or it could be more metaphorical. An alternative suggests it is the month of the God of communication, Ogmha, and there may have been ceremony based on the theme, it is an unlikely etymology.

The hottest month of the year in Scotland is July, and the main holiday month correspondingly (it is also the month with the least chores on the farm). In Gaelic it is An t-Luchar, simply the ‘warm month’. The first great harvest festivals began in the balmy days of August, which in Gaelic is An Lùnasdal. The God Lùgh was a hero god, of skill, artistry and war, and seems to have had a pan-Celtic appeal. The name derives from root words for sun, shining bright or lightening; and it may simply correspond to the long blue-sky days of August, or to the lightning storms that accompany the humidity. Either way, he was a popular figure in Celtic mythology, and the bread feasts were almost certainly dedicated to him. In old Scots the Lammas (or loaf-mass) fair took place in August, and there may be a linguistic connection.

The final month of the summer is September, which is known as the fattening time: An t-Sultain. Here you can see the cycle of the year creaking back towards the winter ahead, and the start of the preparations to see the village through those harsh days on the horizon, and the cattle needed to be fattened now if they were to survive. With the passage into October the calendar moved into Am Foghar, autumn. The root of this word is fogh, meaning hospitality. This is the time for festivals, feasting on the harvest riches, drinking of the ale made from the corn finally brought in: one last Hurrah before stocking up and bedding down for winter.

Out in the hills nature too is preparing for winter, and for the spring that will surely follow. The Red Deer stags begin their bellowing and rutting; fighting with those huge antlers for the right to control and have sole mating rights over their harem of hinds. So, October is known as An Dàmhair, the ‘stag or rutting month’. As the first frosts start to bite, and the snow returns to the high peaks, our villagers know that the great festival of fire and water, Samhain is nigh. This is last feast of the autumn; a time to cleanse the village of evil spirits, to go through ritual and trial, and to pray for a benign and short winter. The festival lasted for two days, but the Gaelic calendar affords the whole month of November as An t-Samhain due to its importance.

And so we are back where we started; a whole year of events, festivals, tasks, observance and respect for man, nature and the gods colouring the life of our ancestors’ lives. The language retains now in name only, that which was either sacrosanct or vital for the farming community; but it gives us a chance to see the world through their eyes, and just perhaps glimpse the last fragments of the Neolithic.

Leave a Comment