Gulls screech overhead, waves crash against the rocks below, and in the distance sits the gentle curve of the horizon where the ocean meets the sky. I am at Cape Finisterre – the headland at the end of the world. It lies at the southern end of the ‘Coast of Death’, so named on account of the number of ships that have floundered on this treacherous stretch of Atlantic coastline.

Long before Christianity adopted Santiago de Compostela as a place of pilgrimage it was Cape Finisterre that was the spiritual magnet for Europe’s ancient tribes. From here at the end of the day they watched the sun disappear over the horizon into another realm.What lay beyond that horizon would take many more centuries to discover but it was connected with where I headed next.

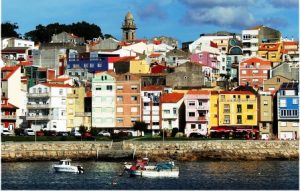

To the south of Cape Finisterre lie the Rías Baixas (Lower Rías). Rías are large bays into which rivers flow forming large estuarine habitats. Four of these define the southern stretch of coastline towards Portugal. As I travelled south the landscape grew less rugged. Here the hills roll towards the sea and the power of the Atlantic is tamed through a combination of islands, shallower water, and an undulating shoreline with many outstanding beaches. Rías are important ecosystems. The mingling of freshwater and saltwater over tidal, sandy basins creates unique habitats with rich food sources essential to a wide range of bird and marine life. The excellent quality of these habitats is one reason why seafood harvested from them is so prized. To complement the outstanding seafood are great wines – perhaps none more so than the beautifully aromatic whites from the famed Albariño grape grown on the surrounding hillsides. There are more than 8,500 acres of vineyards and 6,500 growers capitalising on the region’s mild, wet climate.

It was early afternoon when I arrived in Pontevedra, the principle city of Rías Baixas. I took a walk along the Río Lérez and crossed the elegant suspension bridge, Ponte dos Tirantes. I wandered into the historic centre and found myself in a world of medieval courtyards, churches, crucifixes, colonnades, fountains and the quirky architecture of doors and windows that offered a glimpse into the past. Sitting under the shade of an umbrella at a café in Plaza de la Leña, I ordered Pementos de Padrón and a beer. Pementos are small green peppers grown in the municipality of Padrón. They are fried and liberally sprinkled with sea salt to create a Galician speciality. There is even an annual festival celebrating this delicious little pepper.

The following morning, courtesy of Turismo Rías Baixas, I met Patricia Furelos in the old town. She has been a Galician Tourism Licenced Guide since 1998. We walked the streets pausing frequently for her to overlay the stones with history and bring the place to life. Passing by the market we paused near the Río Lérez. Here, Furelos pointed out, one of the most famous ships in history was built – La Gallega, later renamed Santa Maria – the flagship of Christopher Columbus.

Furelos arranged a car and we headed inland to the Rock Art Archaeological Park at Campo Lameiro. This is one of the most important petroglyph – rock art – sites in Europe. There, I met archaeologist and park director, Jose Manuel Rey Garcia, who took me onto the hillside to see rock outcrops carved thousands of years ago, and showing warriors with weapons, hunters chasing deer, and a myriad of enigmatic circles and lines. Garcia explained that the park raises public awareness of the many important petroglyphs found in the area. It is also an international centre for education and documentation seeking that explores and records the way of life of our ancestors and their art. Inside the park’s main building a stunning exhibition and audio-visual display transported me back through several millennia until, finally, I emerged in the present.

Next we headed south to the seaside town of Baiona. If I learned one thing in Galicia it was the importance of food. Our first stop was the restaurant of the Paradores Hotel that occupies the medieval fortress of Castelo de Monterreal, overlooking the Ría de Vigo. It was in these waters that Jules Verne set part of his famous novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea. It seemed an appropriate place to order Galicia’s most famous dish, pulpoá feira – fair styled octopus.I admit to being hesitant because anytime I have tried octopus before I found it rubbery and indigestible. This was soft and delicate, drizzled with olive oil and sprinkled with sea salt and paprika. Unsurprisingly, it tasted of the sea and was the perfect starter for the mouth-watering paella that followed. Over lunch I asked Furelos what made Galician cuisine so famous. Picking up a scallop she held it against the blue of the ocean through the window and explained, “Galician cuisine is very simple. Everything is made from fresh, natural, high quality products that can be found in local markets.” It may be simple, but it is beyond scrumptious.

Baiona is attractive, with a modern seafront concealing a network of old streets and lanes behind. Dozens of yachts bobbed gently in the bay, but one boat caught my eye; it was a full size replica of the Pinta. Alongside Santa Maria and Niña this caravel completed the trio of Columbus’ ships that had sailed over the horizon I had observed from Cape Finisterre. It was here in Baiona on March 1, 1493 that Pinta became the first boat back to break the news of what indeed lay over the horizon – a New World. I crossed a floating walkway, climbed some wooden steps and ventured on board. At around 55ft (17M) in length, I was struck by how small it was. It had three masts and little storage space. Despite more room below deck it still felt claustrophobic and that was without pitching and rolling across the Atlantic Ocean. Conditions must have been unpleasant for its crew of twenty-six sailors, and even more unpleasant for the natives they captured and brought back with them!

Leaving Baiona, we headed for the ancient Celtic hill fort of Santa Trega by A Guarda. Standing on top of this impressive hill I could see over the estuary of the Río Minho into Portugal, out across the Atlantic and over the rolling green land to the north and east. In 1913 during construction of a road to the summit, the remains of circular stone buildings were uncovered. Subsequent excavations revealed a huge Celtic hill fort.It is only in the last few decades that archaeologists have realized the scale and importance of this settlement. At present a mere 10% of what is now known to have been a settlement of 3,000 people has been uncovered and it reveals a complex social group. Each stone circle is the lower portion of an enclosure that once stood much taller with a conical roof of branches and thatch. A family would have occupied several stone circles, each serving a different function, and all accessed from private courtyards that in turn were linked to communal ‘streets’. Evidence also suggests there was a hierarchy with high status individuals holding prime hillside locations while those of lower status were relegated to ‘poorer quarters’. I walked the streets, stood in the stone circles, and watched the sun sink to the horizon just as my Celtic cousins had done thousands of years before.

Back in Pontevedra, Furelos and I chatted over a drink and I asked her why she considered herself a Celt. In unwavering English she explained, “Philology was my degree at university, so I have been dealing with languages and their evolution for some years. Like most philologists, I believe Galicians are Celtic.”

Back in Pontevedra, Furelos and I chatted over a drink and I asked her why she considered herself a Celt. In unwavering English she explained, “Philology was my degree at university, so I have been dealing with languages and their evolution for some years. Like most philologists, I believe Galicians are Celtic.”

Over the next few days I explored some breathtaking beaches and spent a few days in the large seaport of Vigofrom where, in 1719, a fleet of ships sailed for Scotland in support of the Jacobite uprising. Manyof those vessels were caught in a storm and destroyed on the Coast of Death at Cape Finisterre.

My journey around Rías Baixas and Galicia was ending. I spent a final day in Santiago where my trip through this fascinating region had begun over two weeks before. There was just one final thing I wanted to see – and hear. I followed the sound of music to a covered way by the side of the cathedral and there I paused to listen to a musician playing the traditional Galician gaita, or bagpipes. It reminded me of how much we share as Celtic nations – our culture, our relationship with the sea and above all the friendship and hospitality that I had encountered repeatedly throughout my travels. ~ Story by Tom Langlands

www.tomlanglandsphotography.com

Leave a Comment