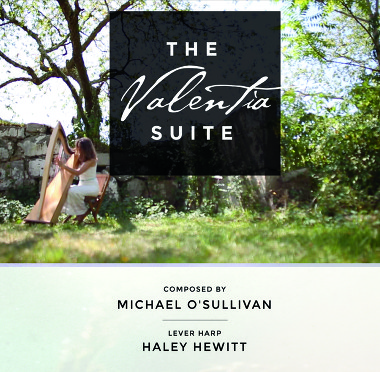

Haley Hewitt

Teacher, composer, arranger, performer and recording artist, American harpist Hayley Hewitt keeps a busy schedule. Recently she spoke with Celtic Life International about her debut recording The Valentia Suite, and her passion for her professions.

Teacher, composer, arranger, performer and recording artist, American harpist Hayley Hewitt keeps a busy schedule. Recently she spoke with Celtic Life International about her debut recording The Valentia Suite, and her passion for her professions.

What are your own roots?

I am a bit of a mutt, but mostly Irish from my father and Czech from my mother. My first name actually comes from my paternal grandmother’s name, Betty Haley. My mother has been very carefully researching our family’s genealogy over the past decade or so, with some interesting results. She found that my great-great-grandfather Patrick Healey was an Irish trumpet player who served as a musician in the Scottish military before moving to Canada, where the family name was changed to Haley.

When and why did you start playing music?

Music has always been important to my family. My mother plays piano, and my father plays fiddle. The house I grew up in is littered with dozens of instruments from around the world – as you look around the house you see kotos, pianos, psalteries, autoharps, dulcimers, guitars, fiddles, drums and mandolins hung on walls and tucked into every nook and cranny! My fondest memories of childhood are of playing and listening to music with my parents. I started playing piano early on, taking lessons from a klezmer musician named Brian Bender. Then, when I was eight, I saw a harp for the first time in a music shop in Vermont. I went straight to it, captivated by its beautiful shape. Within a few minutes, I was able to pick out some of my piano repertoire. My parents, used to acquiring instruments, bought the harp and found a teacher for me soon after. I never looked back!

Are they the same reasons you do it today?

These days, music remains as captivating, curious, and fun as it was when I was a child. I love learning, and with music there is always more to be learned. It’s an inexhaustible mine of creativity, expression, and discovery.

How have you evolved as a performer over that time?

My musical taste and playing style haven’t changed much, but it has certainly broadened. I grew up listening to Fairport Convention, The Beatles, and playing Scottish tunes with my fiddler father. These days, I’m listening to lots of jazz and indie, and spending a lot of time playing Irish and American as well as Scottish music.

How would you describe your sound today?

My playing is very melody-driven. I strive to have as clear and focused a melodic sound as I can, and only then do I try to provide a supportive bed of rhythm and harmony that doesn’t obscure the tune. My playing style also can’t help but be influenced by the musicians I’ve spent a lot of time listening to, and the landscape I’m living in – so mostly Scottish, a lot of American, and some other sounds too.

Is your creative process more ‘inspirational’ or ‘perspirational’?

Definitely both, but only ever one or the other. Occasionally there are those great days where I just have a tune come from out of nowhere that I’m really happy with. But some of the time it’s like a long, long trek, uphill, in the sleet, with soggy socks!

What makes a good song?

I wish I knew! I don’t suppose there’s a secret recipe to writing a good song. The songs with some grit, some truth, songs that sound like it took a piece of the writer’s heart to write – those are the songs that stick with me.

What were the challenges involved with recording the Valentia Suite?

The composer, Michael O’Sullivan, was my flatmate when I lived in Glasgow. Having him around all the time made it very easy to work closely with him. I could approach him with questions, ideas, and suggestions over breakfast, go try it out, then re-approach him over lunch. He was also able to write a lot of the music with my own instrument to hand, so the piece was custom-built, so-to-speak. In the studio, it can be hard to keep perspective on the whole piece, because you can easily get tied up in the tiniest details. It was great having Michael there as producer, because he knows the piece as well as I do, and could make good judgment calls on takes. After the session, Michael and I really saw eye-to-eye on which takes to keep and which to discard. Then the next step was to sort out copyrighting, cover design, disc manufacturing, and all of that boring deskwork. This work proved to be far more challenging to me, being a harpist and not particularly good at admin. But we got it done, and I’m very proud of the finished product.

What were the rewards?

I chose a musical career because I really enjoy making stuff – and that’s just what we did. Not only do we have a physical document of the work as a CD, but we also published a book of sheet music through Fatrock Ink and filmed a cool music video with Barnberry Productions. I’m thrilled with how these turned out. Recently, I received a message from someone who ordered a CD. They wrote that they were so inspired by my playing that they had driven to a harp store, brought home a new harp, and have started learning. This made me so happy!

What has the response been like?

The response has been very positive. I think having such a neat-looking music video made a big difference.

What do you have on tap for the rest of 2014?

I recently moved to Boston, a great city for traditional music. So lately, I’ve been spending a lot of time soaking in the music scene here and drafting tracks for the next album. For the past two years a team of friends have participated in the Whaling City Film Project, a time-crunch short film competition. We have a screenwriter, a good actor, an excellent filmographer, and I write and record the score. We have won first and second places the past two years, and although the team is very busy this year, we’re going to try and eke another film out. The submissions will be screened in New London the second week of October. I’m also very excited that I’ll be performing at the Boston Celtic Music Festival in January.

Is enough being done to preserve and promote Celtic culture?

We’re certainly trying! I’m encouraged, because I find the general public have a fairly high awareness of what Celtic culture is (even if they do sometimes pronounce the word like the basketball team) and have a genuine interest in the background of that culture. Here in the Northeast of the US, people turn out for concerts in droves, go to dances, and the session scene is very much alive. Thankfully, the tradition is flexible and adapts with each new generation of musicians and proponents of culture. I think that people tend to go in with a deep respect for what has gone before, and a desire to add their two cents to the wealth as it moves forward. It’s because of this attitude of custodianship that the tradition is very relevant today.

What can we be doing better?

Uh oh, you’ve given me a soapbox! Well I suppose one thing that I come up against from time to time in this country is a bizarre notion that there is a ‘correct’ way to play the music, to sing the songs, to tell the stories. Some folks out there feel very strongly that the only right way is exactly the way it was played in the 18th and 19th centuries when the culture emigrated to the USA, as though people today don’t have important and valuable ideas to contribute. This philosophy can cause a music to stagnate and fossilize, a problem we see much of western classical music fighting to do away with.

Leave a Comment