The early Celts all over Northern Europe celebrated this day as Imbolc. Imbolc (also spelt “Imbolg”) comes from the Old Irish, “i mbolg” meaning “in belly.” It is associated with the period when female sheep (ewes), pregnant with spring lambs, started to lactate and give milk again — though this onset of lactation can vary up to two weeks before or after the 1st of February. Still, the 1st of February makes for a date that falls about halfway between the Winter Solstice and the Spring Equinox.

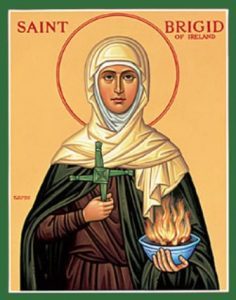

Later, the Church appropriated the date to mark the feast day of St Brigid (of Kildare.)

Considered the first day of spring in Ireland, the date occurs at a time of year when days are definitely getting longer, and nights shorter. In addition to the imminent arrival of spring lambs, you start getting ready to plant, as well as doing your spring cleaning. Sometimes in parts of Scotland it is celebrated on 13th February, which is when it would have occurred in the old, Julian calendar.

In Celtic mythology, Brigid was the goddess of fertility and one of the most loved Celtic goddesses, worshipped by Celts both in the British Isles and in Europe. Her worship may have started with the Celtic tribe called the “Brigantes”, who themselves originated in the area of Austria now known as Bregenz. Brigid also became known as Bride, Brighid, and Bridgit. Some writers feel that the Britannia image on older British pennies and the current 50p piece is Brigid.

Celts believed in the Old Woman of Winter, named “Cailleach.” In the stories, Bride was either Cailleach herself transformed after drinking that morning at the Well of Youth or is a girl that Cailleach had kept prisoner all winter up in Ben Nevis — Cailleach’s son falls in love with her and spirits her away to freedom.

Brigid had a sacred site dedicated to her in what is now the city of Kildare, south-west of Dublin. There was a holy well there, an oak tree sacred to her, and priestesses who kept a perpetual fire. In fact, wherever three streams or rivers met was considered particularly sacred to her.

Christianity transformed her by having angels convey her by air from Scotland to Bethlehem, where she became a mother’s helper for Mary and her new-born baby Jesus. Born sometime between 451 to 453 AD.. in Christian versions of the stories, dying in 525 AD, she became the first nun in Ireland and established the first convent. When she was young, stories say she would only drink milk from a white cow with red ears. She was in charge of her father’s dairy, but gave most of the dairy products away to the poor. Despite this, their pantry was always full. Consequently, she is in Ireland the patron saint of dairy maids.

The Church chose the site that had been previously dedicated to the Celtic goddess Bride, and called the place Cell Dara (“Cell” meaning “church”; “Dara” being a kind of oak tree; now Kildare.) The sisters kept an eternal flame burning for her from the time of her death in 525 AD until 1220 AD when it was relit. It then burnt again until put out by the Catholic Church’s counter-Reformation, which declared the flame “pagan.” Up until then, the Abbesses of the convent there had functioned with the equivalent authority of male bishops. The counter-reformation put “that to rights” too and made the abbesses subservient to priests.

Monasteries and convents were dissolved by Henry 8th (who ruled over Ireland at that time as well as England) over a three-year period from 1536 to 1539. At this time, St Brigid’s convent was abandoned, then crumbled into ruins. Very little today is still extant from the original buildings. There’s still the round tower (which you can still go in), where the nuns would flee if being attacked, and the foundations of the building that the sacred fire was kept in. She is no longer an official saint; the Catholic Church; the Church felt there wasn’t enough proof about her life, let alone that she had ever actually existed in the first place. Consequently, she was decanonized in the 1960s, and is often called now just “Brigid of Ireland.” The Irish, though, still do unofficially call and treat her as a saint — in fact, as one of the two patron saints of Ireland (the other one being St Patrick.)

The order of Brigidine Sisters (Sisters of St Brigid) was restored in 1807. In 1993, the flame was relit in its original place by a Sister Mary Minehanre. However, because the original place of the fire is now just foundation walls, with nothing to protect it from the elements, the eternal flame was transferred into the house of the Solas Bhríde Community.

Some sacred wells are still dedicated to her to this day in Ireland, but in her St Bridgit incarnation, rather than her Celtic goddess one. There are at least 15 “St Bridgit” wells in Ireland. The two best known are at Tully in County Kildare (1 mile south of Kildare proper) and Liscannor in County Clare. A new statue of her was erected at Tully in late 2002 or early 2003. The pilgrimage day for the Liscannor well is oddly enough not St Bridgit’s Day, but Lughnasa, 1st August.

On her feast day, Brigid came (so people believed) round to farms with her cow to bless the people and their animals. An oat bannock (“bonnach Bride”) and a bowl of milk or butter was left on the windowsill or doorstep for her, and some grain for her cow. Fresh butter would be churned; colcannon and barm brack would be made, and if farmers had a sheep to spare, there’d be mutton for meat.

The evening before Brigid’s Feast Day, girls would make a Bride effigy from sheaves from wheat or other grains, or rushes, and decorate it with seashells, spring flowers, etc. The doll was called variously a “brìdeag” (“little Bride”), or a “Dealbh Bride” (doll Bride.) Sometimes the doll was also called “the biddy”, and the girls “biddies.” On the day itself, the girls dressed up in white and paraded through the town, showing off the dolls they had created, visiting homes and accepting gifts offered to their Bride dolls, such as bannocks, or other food such as cheese. Then the girls spent the night in a house keeping the Bride doll with them. Young men would come to join them for a ceilí (also spelled ceilidh) that lasted throughout the night with songs and dancing. The next morning, at dawn, they would wrap up the night with a hymn to the Bride, and give any food left over to the poor.

The evening before Brigid’s Feast Day, girls would make a Bride effigy from sheaves from wheat or other grains, or rushes, and decorate it with seashells, spring flowers, etc. The doll was called variously a “brìdeag” (“little Bride”), or a “Dealbh Bride” (doll Bride.) Sometimes the doll was also called “the biddy”, and the girls “biddies.” On the day itself, the girls dressed up in white and paraded through the town, showing off the dolls they had created, visiting homes and accepting gifts offered to their Bride dolls, such as bannocks, or other food such as cheese. Then the girls spent the night in a house keeping the Bride doll with them. Young men would come to join them for a ceilí (also spelled ceilidh) that lasted throughout the night with songs and dancing. The next morning, at dawn, they would wrap up the night with a hymn to the Bride, and give any food left over to the poor.

Older women made an effigy of Brigid from oats, as well as a basket which they called “leaba Bride” (“Bride’s bed”.) Then they’d go to the door of their homes and call to the Bride, saying that her bed was ready and that she was welcome, and then put the doll in the bed.

In some depictions of Bride, she carried a white staff that she’d tap the earth with to cause spring growth to start, so women would also put a white stick in the doll’s hand. Before going to bed themselves, the women would smooth out the ashes in their hearth. In the morning, they’d hope to find some trace in the ashes that Brigid had come in — either a line in the ashes drawn by her staff, or a footprint.

Parts of the original Celtic ceremony are still practiced in Scotland, such as the bride doll procession from house to house. Even as a Christian saint, Brigid continued to be among the most loved female figure in Ireland; people would say, “Brid agus Muire dhuit” (“May Brigid and Mary be with you”.)

Leave a Comment