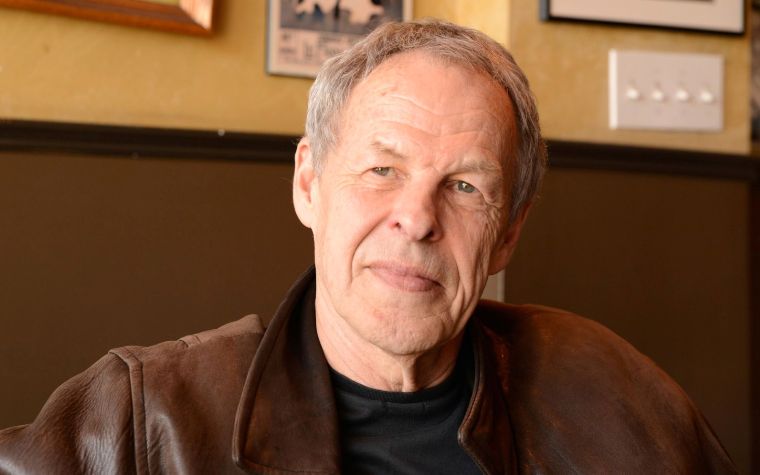

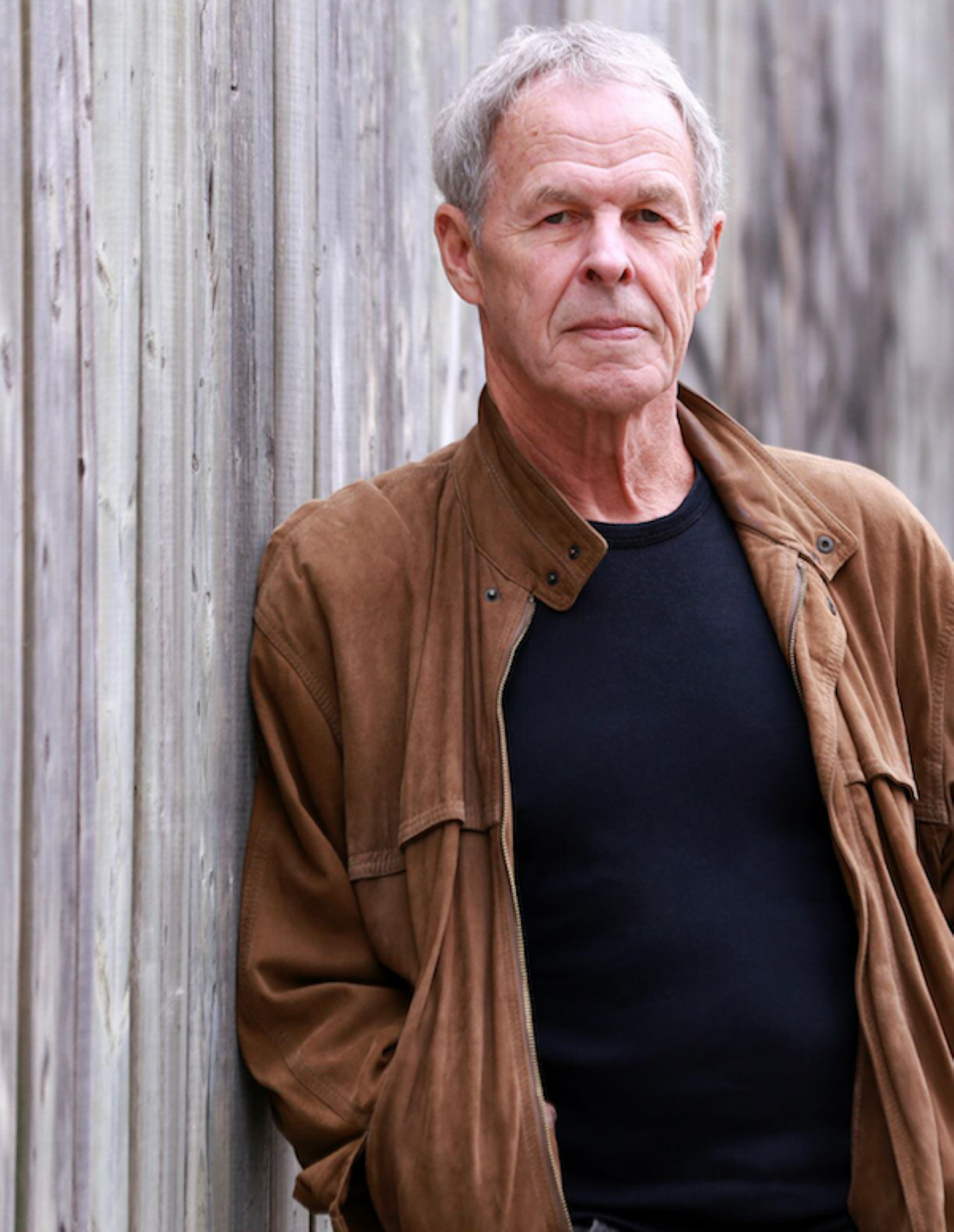

Though he humbly resists the title, Linden MacIntyre is widely regarded as a Canadian literary and media icon. With a career that spans decades – and includes ten Gemini Awards, an International Emmy, and a Giller Prize-winning novel (The Bishop’s Man) – the 72-year-old Canadian journalist, broadcaster, and novelist’s body of work is formidable.

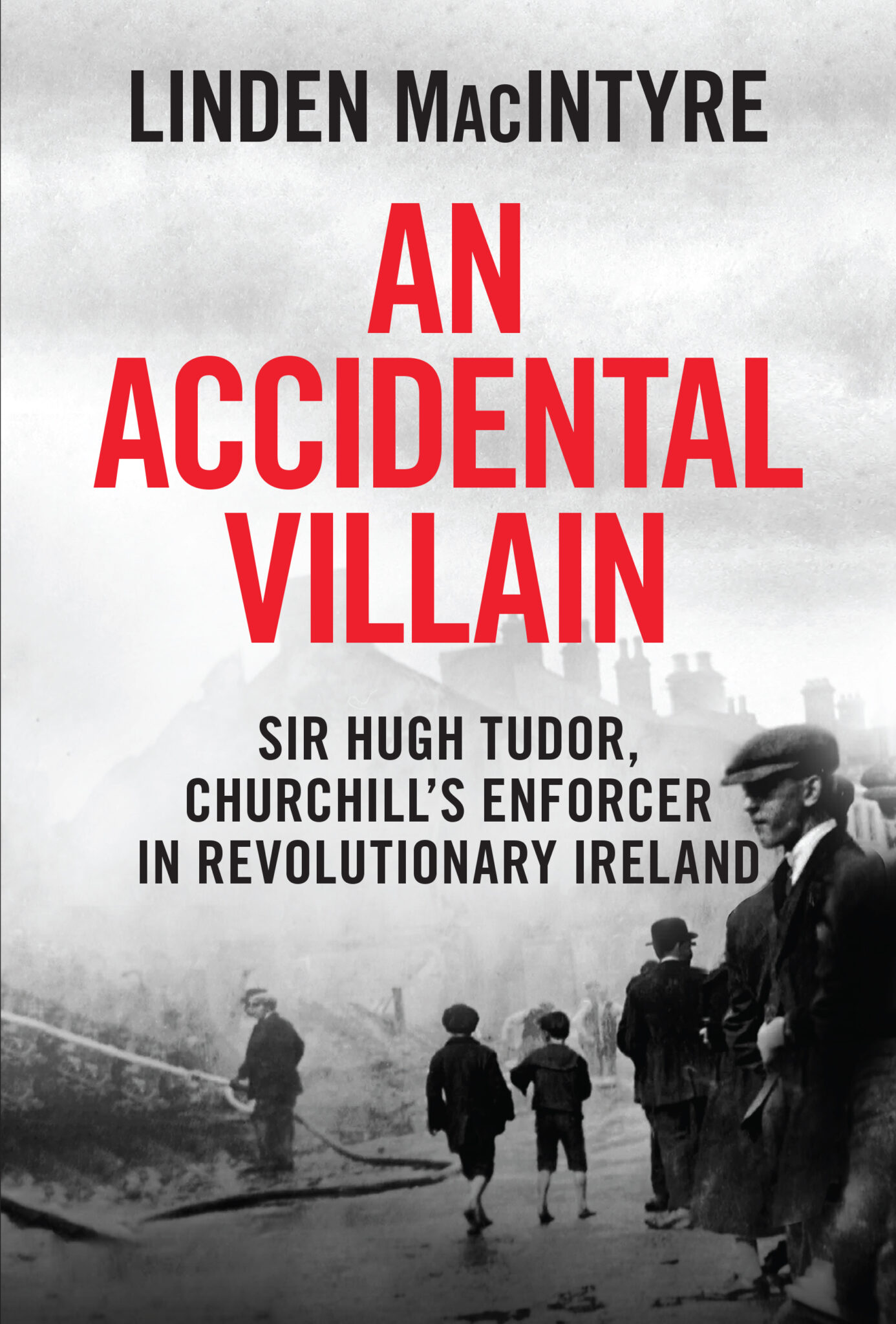

His latest narrative, An Accidental Villain, might well be his most comprehensive undertaking to date.

“You are only as good as your last book,” shares the scribe over the phone. “So, when somebody says it’s a good read, I find that quite rewarding.”

An Accidental Villain is a riveting blend of biography, history, and political critique, centering on the controversial figure of General (Sir) Hugh Tudor, a British military officer and head of the Royal Irish Constabulary during the Irish War of Independence of the 1920s. The book reveals Tudor’s complex legacy, examining how loyalty, duty, and personal conviction collide within a system of imperial power.

One of the author’s greatest hurdles was initially tracking down information, but true to form he quickly adapted. “I discovered online sources I didn’t even know existed. I found a way toward government documents and parliamentary records. But the biggest challenge was dealing with the obscurity of Tudor as a human being.”

That inconspicuousness made the research both painstaking and historically provocative. MacIntyre describes Tudor as a man who “kept his head down and his mouth shut” – especially in the decades following his controversial role in Ireland. “He didn’t write memoirs, didn’t publish diaries, didn’t give many speeches, so people were left to draw their own conclusions, which were often one-dimensional and could be harsh.”

Dedicated to depth and accuracy, MacIntyre’s breakthrough came in the unlikeliest of places – a St. John’s newspaper gossip column that mentioned Tudor bragging about a grandson being accepted to Oxford’s rowing team. That breadcrumb led the author to discover living descendants of the General. “I met one of them, a lovely old chap, who was unsparing in what he could give me. After reading the manuscript, he said ‘I think I have finally come to know my grandfather.’ His acceptance was really telling and gave me a sense of completeness with the portrait that I had patched together.”

Winston Churchill looms large in the narrative as well, and MacIntyre notes that Tudor’s relationship with the-then Secretary of State for War was central to both Tudor’s rise and downfall. “He (Tudor) was completely infatuated with this friendship. When Churchill got in touch after WWI and said, ‘I have a job for you,’ Tudor didn’t question it. He said, ‘Churchill needs me. I’m going to go and do it.”

That ‘job’ was overseeing police operations during Eire’s struggle for independence, which ultimately plunged the dutiful but politically uninitiated Tudor into a storm of controversy.

Although initially detached from the broader implications, Tudor’s personal losses during the conflict ultimately influenced his actions.

“When the IRA murdered a very close friend of his and then that friend’s younger brother, it was a turning point for Tudor, and he became the accidental villain of that piece of history.”

MacIntyre contends that while the protagonist’s orders and tactics were brutal, they were shaped by private sorrow and institutional pressure. “He wasn’t so politically naive by the end.”

Tudor left few traces of his time in Ireland as commander of the Black and Tans. A man caught in the roles of hero, scapegoat, and exile, he never recorded any justification for his role the 1920 Bloody Sunday uprising, or other episodes of bloodshed.

MacIntyre brilliantly constructs a nuanced portrait of the Irish War of Independence by walking a fine line between biography and moral inquiry. “I had to draw on skill sets I developed over decades in journalism – basic research, tracking down people, interviewing, piecing together fragments. At times, I didn’t even realize how blank the slate was until I started digging.”

Those “skill sets” arose from his early days in print journalism through his years hosting television’s The Journal and The Fifth Estate, and later as an award-winning, best-selling author, and equipped MacIntyre with a rare, panoramic view of the media landscape.

He points out that the current media climate is dramatically different from the broadcast era, though its benefits are still being debated.

“We have a problem and it’s not with the people or the storytellers – it’s the delivery systems.”

MacIntyre notes the erosion of traditional media and the rise of unregulated digital platforms. “Who could ever anticipate that radio and TV would be diminished as primary sources of information, replaced by a huge and unrestricted industry of information? I’m not saying information should be controlled by anything more than taste and need, but if anybody can pitch a message that solely appeals to their bias, it can create massive problems for humanity.”

Yet he sees glimmers of hope in new, decentralized forms of journalism.

“The Substack world, for example, has some structure. You see people applying journalistic standards of accuracy, fairness, and clarity, because they have to. There’s no regular payday anymore. The freelance economy demands rigor.”

Despite these shifts, he insists that the core principles remain the same.

“Good journalism is still about curiosity and an honest attempt to understand…”

“Journalism began with someone simply describing what happened that day around a fire; the weather, the hunt, etc. And that is still the most effective way to convey information – through story.”

“Journalism began with someone simply describing what happened that day around a fire; the weather, the hunt, etc. And that is still the most effective way to convey information – through story.”

With his novels receiving both popular and critical acclaim, MacIntyre approaches character, whether real or fictional, with a deep sense of empathy. “You don’t invent emotion, but you have to know enough about yourself to find the traces of the universal condition that is present for almost everybody.”

That understanding of the human experience became a wellspring for his creative process. “When I started writing fiction, I had the voices of people I had interviewed in my head. I just had to bring them out and put them on the page.”

Even after five years spent writing An Accidental Villain, MacIntyre is not quite ready to put down his pen. “I must have said a dozen times, ‘I’ll never write another book.’ But I am actually working on a novel now. It brings me downstairs in the morning and occupies my imagination. And I think I will finish it.”

Readers can expect the same intelligence and insight that have long defined MacIntyre’s work. Whether broadcast to millions or shared on the page, his voice remains unwavering and marked by lasting resonance, courage, and clarity.

In An Accidental Villain, he not only sheds light on a controversial figure but also illuminates the deeper truths of moral complexity, reminding readers that history, like journalism, is never just black and white, but layered and messy, and a story that is always worth telling.

“I’ve been lucky,” he says, “But luck alone doesn’t tell the tale. It’s the art of really listening and absorbing the voices of the people who make up your stories.”

Leave a Comment