Aside from the temperature, mid-winter in Ireland isn’t much different from the country’s other seasons; the landscape is lush and green, and most days are a mix of clear and cloud.

Interestingly, tropical palm trees dot the roadsides in-and-around the small village of Laragh (pop; 320), located in Co. Wicklow, about 75 minutes south of Dublin by car. It is not an uncommon sight, as the top end of the warming Gulf Stream gently brushes the country’s eastern and southern coastlines, leaving robust foliage in its wake. Along with Donegal, Wicklow – known as the ‘Garden of Ireland’ – is my favourite spot on the Emerald Isle.

I had not been to this part of Eire since my first solo trip here in 1989. Photographs of that “pilgrimage” bring back memories of late nights at local pubs with like-minded travel companions, a few fisticuffs, and horrific morning-after hangovers.

This trip would be different, however; for one thing, and due in some part to my boozing and brawling here 35 years ago, I gave up the bottle and the battles for good. And, this time, there would be little, if any, socializing.

The thought of taking a weeklong silent retreat sprang from the writing wells of our Winter 2024 cover story; The Celtic Pilgrimage. After speaking with several Celtic scholars and spiritual leaders for the article, my interest in a proper pilgrimage was piqued and I avowed to undertake my own.

I loved the idea of it – and that was the problem.

I have spent most of my 57 years on this planet living in my head, blessed and/or cursed with a thing for all things theoretical. In particular, Aristotle’s adage that “small minds talk about other people, average minds discuss events, but great minds are interested in ideas” has remained at the forefront of my thinking for decades.

As a young man, I read everything I could get my hands on – from the subtle stylings of Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Albert Camus to the whimsical works of Dylan Thomas, Jack Kerouac, Tom Robbins, and Charles Bukowski.

Later, in college, I studied philosophy, psychology, sociology, history, art history, political science, and, of course, journalism. The decision to pursue a university degree in journalism made sense at the time, as the opportunity to format those big ideas into smaller, more digestible morsels of truth was too tempting to pass up.

After university, I developed an interest in world religions, deep diving into scriptures from the Bible, the Koran, the Torah, and other Holy tomes. Eventually I found my way to magic and mysticism, even exploring the esoteric for a couple of years.

Although raised in a religious home and actively involved with the church as a youngster, I consider myself a “recovering Roman Catholic” and, by the age of 25, had adopted atheism. In fact, I identified as an ‘apatheist’ – meaning that, for me, the question of God had become…irrelevant.

While no longer of religious conviction, there was certainly space for the sacred in my life.

Again, the attraction of the sacred were the principles at play. Over time, the implementation of these strategic ideas into daily tactical practices helped me to create a living philosophy – stars by which I still steer my ship.

Even with a strong sense of the spiritual, however, I have long-felt a longing for belonging to something deeper and more meaningful.

—————————————-

After 15 hours of travel from Montreal, I touch down at Dublin airport and make my way through Customs. There, an officer asks me “What is the nature of your visit to Ireland?”

“I am here to find God,” I reply with a grin, raising an eyebrow.

He looks up at me and, without missing a beat, deadpans “Well, if you do find him can you remind him that I’ve a lotto ticket for this weekend’s draw and wouldn’t mind his consideration.”

I laugh, wish him well, and depart to find my car. For a country that author Leon Uris once called “a terrible beauty” – due to the heaviness and horrors of its history – there is an abiding lightness to Ireland; the humour of its people, the soft sunshine and softer rain showers, and a sense of spiritual luminosity.

Fittingly, I am travelling light, with only an old backpack and a small leather “weekender” bag to haul the essentials; clothing, toiletries, writing materials, a few books – including my well-worn copy of John O’ Donohue’s Celtic spiritual treatise Anam Cara – my compass, my camera, and my laptop.

Just over an hour later I am standing at the main office door of the Glendalough Hermitage Centre. Constructed in 1998, the facility slopes down the side of Brockagh Mountain and sits just a kilometer from the Monastic City, a series of stone structures built by the 6th century monk St Kevin. Long a pilgrimage destination, Glendalough – Irish for The Glen of Two Lakes – is considered one of Earth’s “thin places” where the barrier between this world and the next is marginal.

Just over an hour later I am standing at the main office door of the Glendalough Hermitage Centre. Constructed in 1998, the facility slopes down the side of Brockagh Mountain and sits just a kilometer from the Monastic City, a series of stone structures built by the 6th century monk St Kevin. Long a pilgrimage destination, Glendalough – Irish for The Glen of Two Lakes – is considered one of Earth’s “thin places” where the barrier between this world and the next is marginal.

Orbiting the Church of St Kevin, the Center is comprised of a main administrative building, a Coach House, a meditation garden, and five small residences for guests. A Sister of Mercy from Dublin, Peggy Collins, oversees the property and, after a few brief instructions, escorts me to my home for the next seven days, the wonderfully-monikered Cillín na Trionoide, or ‘Little Trinity Church.’

The room is basic; a single bed, a table with chairs, a rocking chair, a lone lamp, with a small kitchenette and bathroom at either end of the structure. There are only the barest of necessities – some linens, a few plates, a mix of cups and glasses, a fistful of utensils, pots and pans, a toaster, a microwave oven, a burner stove, and, in true Irish fashion, a kettle, a tea pot, and a topped-up tin of tea bags.

The centerpiece of my new quarters, however, is an old wood stove. Given the cold and damp, I quickly learn to keep that fire going at all times, stocking up daily on paper, kindling, and logs. To complement the light and heat, I place slabs of dry turf into the flames to invoke the sweet scent of Ireland of yore.

Aside from a weak signal in the main building, there is no internet. For the most part, I am cut off from the world in self-imposed exile. And though, at first, I am stricken with a deep sense of disconnection, the opportunity to unplug from my digital devices soon washes over me with welcome relief.

After settling in, I sonder into town for supplies; coffee, milk, soup, soda bread, Kerrygold butter, and a few other small items. Exhausted and hungry, I return to eat and grab a quick nap.

That evening, Sister Peggy leads a 30-minute silent prayer session in the main building’s makeshift chapel. There are four of us on our knees, including a local Pastor and an American woman. I have not prayed since my cancer diagnosis in 2015, so I am a little out of practice. Still, I keep an open mind and recall the words of a mentor years ago, “everything you know about God is always up for renegotiation.” Within minutes, both The Lord’s Prayer and the Hail Mary echo through my head, drawn from memory.

The words are comforting as I repeat them in a pseudo-meditative state, and, after the half hour, I feel calmer and more peaceful.

Later, I explore the facility’s well-stocked library, which offers a feast of both fiction and non-fiction books. My fingers run the length of several spines on the shelf, and I pick out an armful to bring back to my room, including Celtic-Christian works by John Philip Newell and Esther de Waal. I also pluck one of my favourites, Marianne Williamson’s Illuminated Prayers. Books of poetry by Seamus Heaney and WB Yeats are borrowed as well.

One title jumps out at me; The Celtic Heart, an anthology of prayers and poems by Pat Robson. I open the volume and find a curious bookmark with the following inscription;

“An echocardiogram uses sound waves to create images of the heart, highlighting blood flow. From the test, health professionals can accurately assess the condition of the heart.”

Interestingly, an echocardiogram is also known, informally, as a “Test for Echo.”

Albeit odd to discover a medical definition in a book on Celtic spirituality, I do not believe in coincidence and the significance of this passage would become apparent over the coming days.

———————————

As it is with my home life, routine hallmarked my days in Glendalough; mornings were alight in prayer and meditation, afternoons came alive with hikes of area trails, and evenings were awash with reading, writing, and listening to music.

As I have learned over time, prayer and meditation are elements of conversation. Prayer is the active art of talking to God (or some similar namesake), while meditation involves listening. With prayer, one sends a signal to the ‘Source’ (or, again, some similar namesake), hoping that it will ‘echo’ back through meditation.

Authentic prayer isn’t for the faint of heart – both the words and intent must come from a place of deep inner truth, and, sometimes, that truth isn’t pleasant. After reading a few passages from various prayer books, I put down the pages, get down on my knees in front of the fire, clasp my hands together, bow my head, and begin mumbling humbly. As I have learned (most often the hard way), if I am unwilling to get humble then I shall be humbled.

As soon as I let my guard down the tears come fast and fluid – remnants of childhood traumas, addiction, divorce, cancer, and other life hazards. In addition, the current pressures of family issues, ongoing health challenges, and work-related matters have been weighing heavily on my mind in recent months. And though I am cognizant of these problems from a rational perspective, I have avoided their emotional gravitas for as long as possible.

It is said that the greatest distance in life is the trail from the head to the heart, and – clearly long-overdue – I cry each morning for the first three days. Through trails of tears, I pray and meditate, all the while aware that it is entirely possible that my devotions are falling upon deaf ears. However, there is no denying that I begin to feel…lighter.

Meditation doesn’t come as quickly – again, like prayer, I am out of practice. For years, I believed that meditation was some sort of other-worldly, abstract, ethereal experience. In truth, the Buddha attained enlightenment through a simple breathing exercise designed to quiet the mind – enough so that one might hear the ‘echo’ of the universe. After all, the words ‘silent’ and ‘listen’ are anagrams.

My afternoon hikes through the mountains of Wicklow – where I “embraced the empty space” – became my own kind of echocardiogram; the crunch of my old Italian leather boots on semi-groomed paths, the humming of a melody, the rise and fall of my breath…all bouncing off the area’s heather-sheathed hills and valleys, echoing back to me. On average, I walk 10-12 kilometers each day, a camera my only companion. These daily outings were always followed by a short nap, a cuppa’ tea, and a light meal.

After dinner, I would attend the daily prayer session in the main building before returning to my room for a few hours of reading, writing, and music. Before bed I made sure to check in quickly with my wife and kids.

Music became a vital component of my pilgrimage experience, and each night my little room rollicked and rolled to the sounds of Van Morrison, Hothouse Flowers, Sinead O’Conner, The Waterboys, Enya, Christy Moore, and more. I also sampled music from area artists, including Órla Fallon, Aoife Doyle, and others. I note that Paddy Moloney of The Chieftains, whom I interviewed in person in 2018, was laid to rest in St Kevin’s graveyard, not 100 yards from my door.

Two recordings were on repeat all week; Mark Knopfler’s stunning soundtrack to the 1984 Northern Irish film “Cal”, and Clannad’s mid-80s masterpiece “Macalla.” Each shook and stirred my soul, cleansing me from the “dust of everyday life” (to quote Picasso).

The music of U2 was an ever-present soundtrack as well, with frontman Bono’s lyrics from the song Cedarwood Road echoing back to me several times over the seven days.

“A heart that is broken is a heart that is open…”

By day’s end, laying in bed amidst the solitude and silence, the only sound left was the gentle rhythm of my own beating heart, keeping time and keeping me company, the meter and measure of a life. It was in those moments, alone with my thoughts and feelings, that I returned again and again to a single question; what was the source of this frequency?

Slowly, almost excruciatingly, I was awakening to the possibility of a Higher Power.

——————————

For the longest time I subscribed to (French philosopher) Albert Camus’ theory that life is absurd as we are finite beings trying to comprehend the infinite. Thus, he deduced, the only meaning or purpose to our existence is the one we give it. However, as the author noted in his groundbreaking work The Myth of Sisyphus, “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Conversely, another literary mentor, Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung, wrote of being a part of something greater than ourselves that he called “the collective unconscious” – arguing, though empirical evidence, that there is clearly more to our lives than meets the eye. It was Jung who definitively differentiated between spirit and soul; the former a collective life force that inhabits all living beings, the latter a unique individual’s expression of that spirit.

I loved that idea – and, again, that was the problem.

In short, cerebral truths are distinct from the realities of the heart. As a bio-computer, the brain can be programmed with various operating systems – information, or data, goes in through the senses, gets sorted, and we adapt to the external world accordingly. In fact, some argue that intelligence is defined by our ability to adapt to change. And while rationality, a long-viewed trait of the eternal masculine, is essential for our sheer survival, dependency on reason alone makes life two-dimensional.

Matters of the heart are a different thing altogether. Long associated with the qualities of the eternal feminine (emotion, intuition, empathy, etc.), the heart brings a kaleidoscope of colour, flavour, and texture to life. Without those elements, our existence would seem merely mechanical. Again, however, a life lived from pure emotion can be unbalanced, and even dangerous.

Matters of the heart are a different thing altogether. Long associated with the qualities of the eternal feminine (emotion, intuition, empathy, etc.), the heart brings a kaleidoscope of colour, flavour, and texture to life. Without those elements, our existence would seem merely mechanical. Again, however, a life lived from pure emotion can be unbalanced, and even dangerous.

In truth, I have spent most of my life running from my feelings. Even after more than three decades of continuous sobriety and almost 20 years of therapy I still struggle to identify, process, and express my emotions in a healthy, coherent manner.

Deeper still are “soul truths” – which, many believe, come to light once the head and heart are aligned and open.

Many cultures – including the Celts – believe this is the sacred space where wisdom lay within us; a deeper awareness and understanding of our true essence and identity.

Try as I might over the first 72 hours, I was unable to access this deeper knowing. I found some comfort in the words of spiritualist Marianne Williamson; “before the new can show up and settle in, one must let go of the things that no longer serve us…” I understood that to mean that if I were to have some sort of spiritual or emotional recharging during my time in Ireland, I had to release my outdated perspectives – much of that via my tear ducts. As stated previously in The Celtic Pilgrimage story, “spiritual awakenings are usually preceded by rude awakenings.”

On my fourth day I experienced a breakthrough, if only for the briefest moment, thanks to the area’s most celebrated citizen, St Kevin.

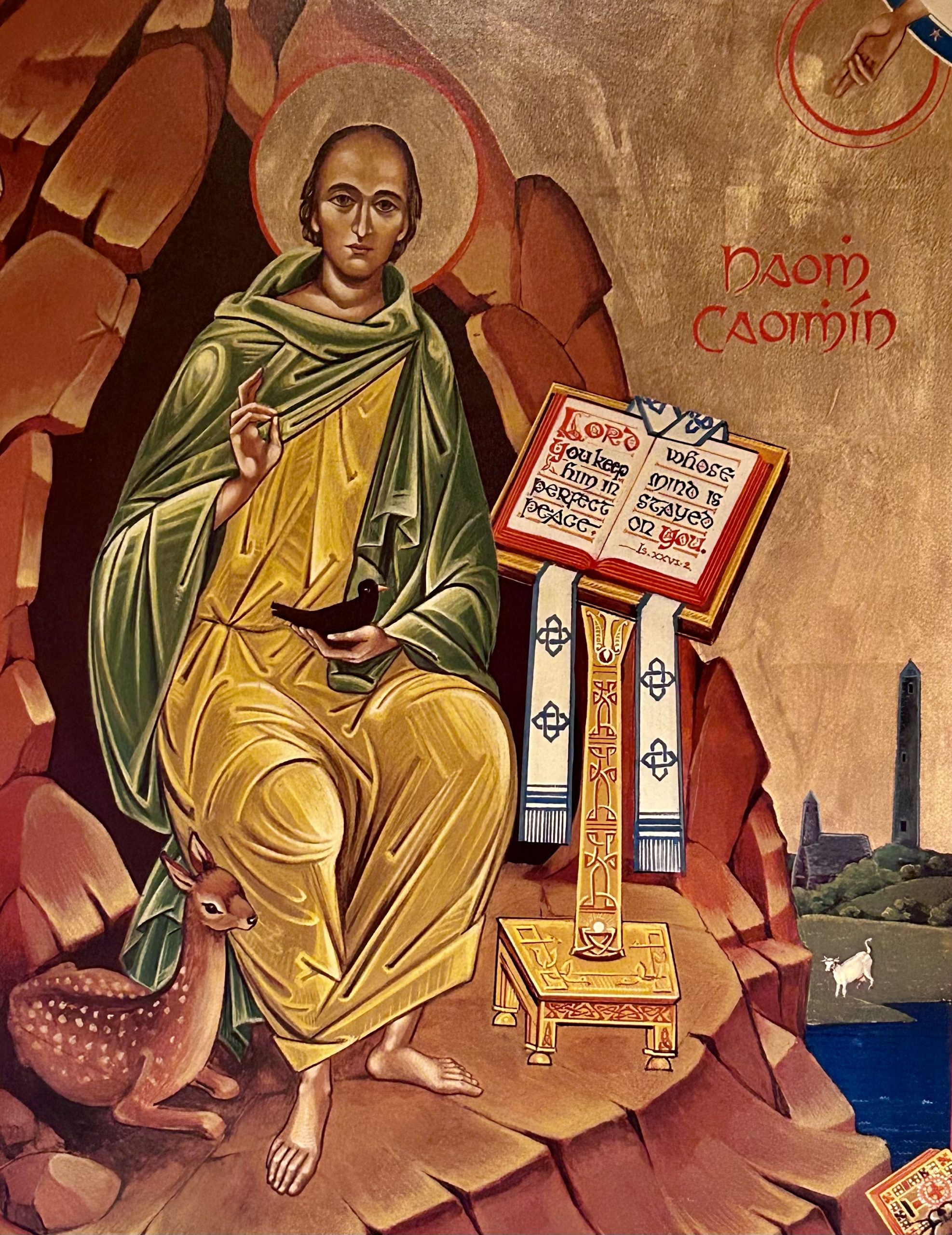

Born in 498 AD in the Kingdom of Leinster, St Kevin relocated to Glendalough as a young man to pursue a life of worship. There, he lived as a hermit in a cave – a site today known as St. Kevin’s Bed – carved into the side of the mountain overlooking a lake. He spent most of his days in prayer and contemplation, living off the land, and immersing himself in nature. He enjoyed a unique bond with animals and, supposedly, could communicate with them directly. In time, he would build his Monastic City in an effort to better echo the good word. He is also reputed to have performed many miracles during his lifetime, including once when a blackbird landed in his hand, laying an egg. Kevin stayed in his position until the egg hatched. The famed monk lived by the lake until his death in 618 AD.

St. Kevin’s story is one of being in harmony with nature – a testament to the power of solitude, contemplation, and a simpler way of life.

Those ideas were on my mind as I hiked past the town of Glendalough, through the Monastic City, and onto the pathway leading to St. Kevin’s Bed. Despite the cool, crisp air and the threat of rain, the trail was packed with people out for an afternoon stroll. As I passed the smiling faces – individuals, couples, families, friends – I was reminded of the power of that simple, single gesture – and its contagious quality – and I soon found myself smiling back.

Then, quite suddenly, the sun broke through the clouds. As it did, I felt the tiniest crack open inside of me – albeit for only a split second – as if a layer of old crust around my heart was breaking off.

Truth be told, I actually heard it break open – a sound akin to the splitting of an old oak tree. Interestingly, in Celtic mythology, oak trees are gateways between worlds. In addition, and perhaps ironically, one question that has come up for me repeatedly over the course of my life has been “what is it inside of an acorn that pushes it to evolve into an oak tree?”

More than a query, that question became a lifelong Koan of sorts. By definition, a Koan is “a paradoxical anecdote or riddle, used in Zen Buddhism to demonstrate the inadequacy of logical reasoning and to provoke enlightenment.”

Clearly, when it came to God, the brain would be of little use on its own. Similarly, the mere feeling that there was some sort of Higher Power at play in my life wasn’t sufficient. Still, that sensation and sound came from somewhere – some “Source.”

Clearly, when it came to God, the brain would be of little use on its own. Similarly, the mere feeling that there was some sort of Higher Power at play in my life wasn’t sufficient. Still, that sensation and sound came from somewhere – some “Source.”

Seconds later I felt a powerful heat envelop me, like I was being wrapped in a big woolen blanket. Amazingly, waves of warmth began to arise from both my chest and through the palms of my hands. I stood a moment by the water, bathing in light and basking in joy. I had never felt anything like this in my life – elevated, engaged, enlightened.

And then, just like that, the feeling was gone. The silence enveloped me. I stood, staring silently at what appeared to be a Celtic “Tree of Life” – unsure whether to laugh or cry, when a still, small voice echoed one single word in my soul; “Serve.”

——————————

On my final evening, I partake in an hour-long prayer session with Sister Peggy. As part of the exercise, we take turns reading devotions from different sources. Perhaps as a tribute to my Loyola High School (Jesuit) roots, I opt for the Prayer of St. Francis of Assisi.

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace:

where there is hatred, let me sow love;

where there is injury, pardon;

where there is doubt, faith;

where there is despair, hope;

where there is darkness, light;

where there is sadness, joy.

O divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

to be consoled as to console,

to be understood as to understand,

to be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive,

it is in pardoning that we are pardoned,

and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life.

Amen.

Peggy then asks me to “echo” back to her what I have just recited.

“Well, to me, it speaks to the three-point axis upon which all religious and spiritual movements pivot; mystical death, alchemic rebirth, and the sacrifice for humanity.”

“That’s great,” smiles Peggy. “Now, in English please.”

I laugh. “It means to get out of one’s head, get into God consciousness, and help others. Self-mastery and service.”

“Yes,” nods Peggy. “That’s it exactly.”

“Actually,” I continue, “it reminds me of Marianne Williamson’s definition of a miracle – a miracle is the transitioning from fear to love.”

Peggy responds, “Yes, correct. In fact, a proper interpretation of Christian scripture reminds us that Heaven and Hell are symbolic states of the self; Hell is being trapped in self, while Heaven is freedom from self. Ultimately, the message of St Kevin – and of Celtic-Christians everywhere – is one of reconciling our humanity and our divinity, and the alignment of our will with that of the Spirit.”

There is a brief pause before she queries, “Stephen, what do you believe?”

I bow my head and breathe deeply. “I believe in nature and in art. For me, nature reflects the external world, while art is the visible link in a chain of internal activity.”

“Good, good,” says Peggy. “And where do those things come from?”

She’s got me, I have no answer. My mind races for reason, the synapses in my brain firing at full velocity, but there is no signal – nothing but static. And then I feel it – the heat coming through my heart and from the palms of my hands. I am alight with the light of love.

She’s got me, I have no answer. My mind races for reason, the synapses in my brain firing at full velocity, but there is no signal – nothing but static. And then I feel it – the heat coming through my heart and from the palms of my hands. I am alight with the light of love.

“So, how can I serve?” I ask, looking up.

Sister Peggy looks deep into my eyes, the mirror of my soul.

“Go and echo the good word…”

~Story by Stephen Patrick Clare

Leave a Comment