Located in a peaceful valley on the banks of the river Esk in Scotland, Kagyu Samye Ling was the first Tibetan Buddhist Centre to have been established in the West.

The colloquially named ‘Muckle Toon’ – literally meaning ‘big town’ – of Langholm, Scotland is something of a misnomer. It is an attractive small town, albeit with a big, friendly heart. The grey stone houses with their slate roofs owe more to its expansion during the heyday of the textile industry than the previous centuries of being a market town in a farming community.

Heading north from Langholm takes travellers through the picturesque valley of the Border Esk. Flanked by undulating hills, this beautiful river meanders through the Scottish Lowlands. In the remote area of Eskdalemuir, the road takes a few gentle turns, and, in an instant, you are transported to the other side of the world. Here, among the trees by the river, lies Kagyu Samye Ling, one of the largest Tibetan Buddhist Centres in the western world.

The facility’s origin goes back to 1959 and the uprising in Tibet against Chinese domination. The Chinese crackdown was swift and ruthless. Two nineteen-year-old Buddhist lamas took responsibility for some three hundred refugees of all ages, and on foot, horseback, and with pack mules the young spiritual leaders attempted to lead the refugees across the vast Tibetan landscape to safety. They were relentlessly pursued by the Chinese authorities. Forced towards India, it became a journey, in freezing winter conditions, through perilous Himalayan mountain passes strewn with raging rivers.

They travelled by night, could not light fires for fear of being seen, and soon found themselves without food. Many died on the route. At one stage they crossed the Brahmaputra River, which was guarded by troops, in makeshift boats. Although the lamas made it to the other side, the troops opened fire. Some of the refugees were killed and many captured.

Ten months after taking flight, the two lamas, Akong Rinpoche and Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, led an exhausted, emaciated group of fifteen survivors into India. It was a journey that had taken an enormous physical toll but one that was to provide enough spiritual strength to last a lifetime. Later, Akong Rinpoche reflected that some of them were still wearing valuable jewellery, but despite material wealth had expected to die.

He considered it a lesson that taught him to help others.

The first refugee camp to which the lamas were taken was in Assam. It was run by Freda Bedi, an Englishwoman. She felt enormous compassion for them and kept in touch after they were moved to other camps. Months later, she invited the lamas to stay with her in Delhi, where she taught them English. She was aware of a blossoming Buddhist society in England, and she arranged for them to travel there. They settled in Oxford where, with sponsorship, Trungpa Rinpoche studied English and Akong Rinpoche, who was a Doctor of Tibetan Medicine, trained with the Red Cross. Soon after, they sought a space to establish a Tibetan Buddhist Centre and continue their important work as lamas.

I travelled to Samye Ling and met with Ani Lhamo, a Scottish woman brought up near Fort William. She first visited Samye Ling in the early 1980s, became a Buddhist nun five years later, and spent a further four years in retreat. Now she is secretary to Lama Yeshe, abbot of Samye Ling and brother of Akong Rinpoche, spiritual leader at Samye Ling. She explains why the lamas chose to establish their Buddhist centre in Eskdalemuir.

“Akong Rinpoche and Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche came to Oxford in 1964 to study English. At that time there was a small Buddhist centre where Samye Ling is now. The people there invited the Tibetans to come during their holiday time and teach meditation. In 1967, the English course in Oxford ended and the people in the Buddhist centre moved to Canada. The lamas took over the centre and named it Kagyu Samye Ling.”

Many of the people who live in Eskdalemuir have connections with the Buddhist centre that stretch back to its beginnings. Nick Jennings was 18 years old when he first visited Samye Ling in the summer of 1969.

“I had been interested, like many teenagers, in the existential questions of meaning, purpose and identity and was very involved in our own local version of counterculture,” he says. “I saw myself as part of a new fraternity of experimenters and explorers sometimes known as hippies.”

It was a time of change – of the old, established ways being challenged by new beliefs. The dawning of the Age of Aquarius made some see the world through a kaleidoscope of art-related, drug-induced imagery. It also opened up different ways of thinking.

Jennings recalled, “I first heard about Samye Ling during a night-long discussion with the not-yet famous performer David Bowie and the radical underground journalist Mary Finnegan. I was sharing my youthful angst about what I saw as the pointlessness of all the conventional life pathways that seemed laid out ahead for me and my concerns about the lack of any authentic spiritual depth in any of the religions that I was exploring. David suggested that I take a trip to Samye Ling.”

Back then, it was no more than a two-storey sandstone house in a remote valley.

Trungpa Rinpoche provided most of the teaching and was always in great demand at other centres in the U.K. and abroad. He visited the USA on several occasions and felt drawn to continue his work there. He left Samye Ling for the USA in 1971, leaving Akong Rinpoche to decide if, and how, Buddhism was to develop in this remote corner of Scotland. If it was to develop, Akong Rinpoche’s teachings would need to inspire many hearts and motivate many hands. As it happens, that wasn’t a problem – work to construct a temple started in 1979 and Jennings became one of a group of resident volunteers that laboured on the building of the temple.

Since then, Samye Ling has expanded enormously, and Ani Lhamo has witnessed most of these changes.

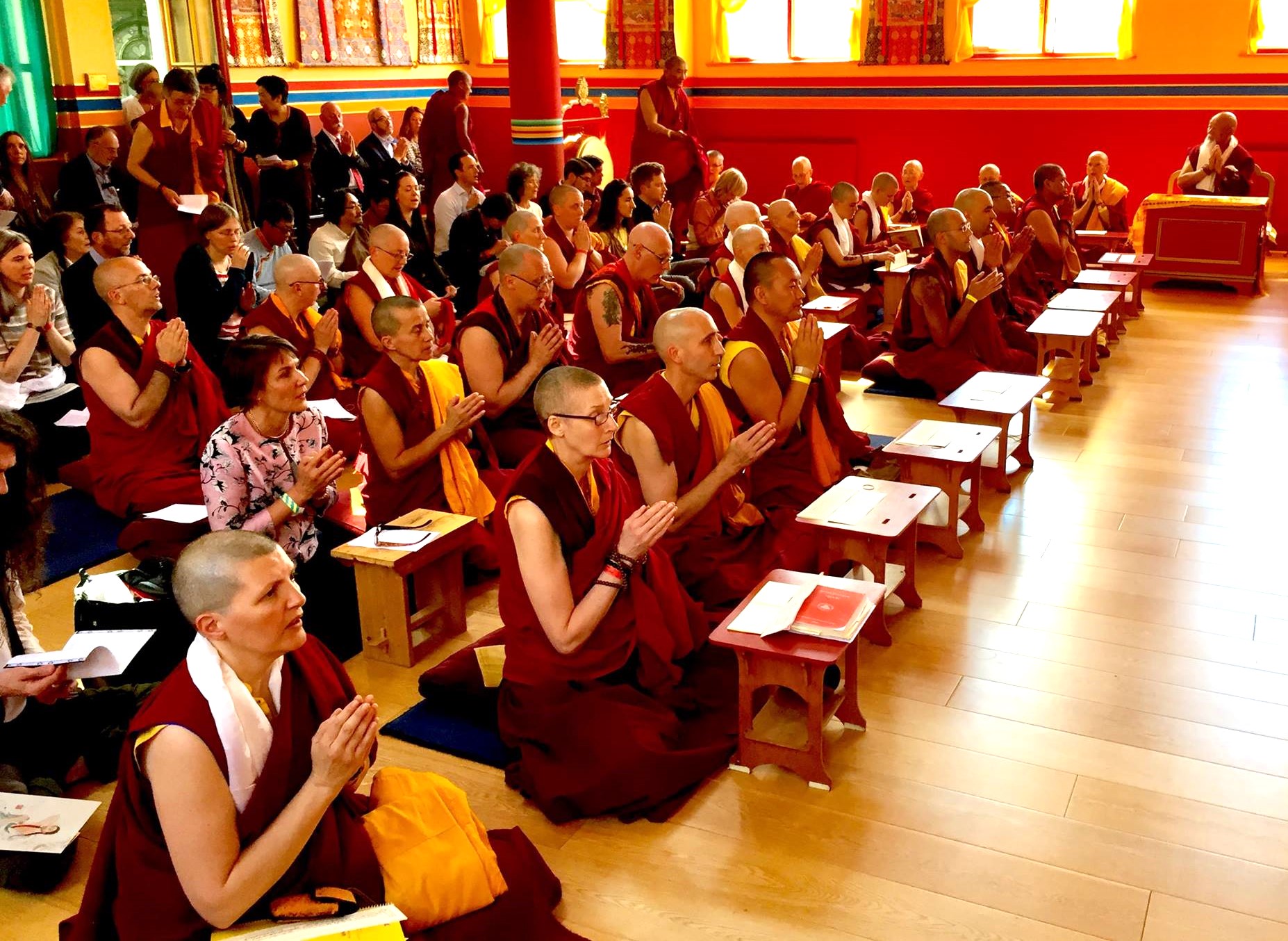

“Now there is a total resident population of around 60 monks, nuns, and lay people at Samye Ling. Every year, around 30,000 people visit and 3,000-4,000 come to stay in guest accommodation and to attend courses or retreats.”

At first glance, the fluttering prayer flags and golden statues, the tall white stupa, and the temple with its sweeping golden roof and brightly coloured walls, seem incongruous in this Scottish setting. Yet, it is wholly appropriate that the Buddhist teachings of kindness, compassion, wisdom, and understanding should emanate from such a tranquil location, which apparently bears great similarity to the landscape of Tibet.

From this very special place, Akong Rinpoche reaches across the globe and continues to guide and teach. Lama Yeshe is responsible for the running of Samye Ling but also spends time on the Holy Isle, close to the Isle of Arran off the Scottish west coast. The island has a significant spiritual heritage associated with the spread of Christianity but is now under the ownership of Samye Ling. Part of the island is used by the Buddhists for closed retreats, but Lamye Yeshe has established a Centre for World Peace and Health on the island where he runs projects irrespective of participants’ background or faith. ~ Story by Tom Langlands.

Leave a Comment