It was the greatest moment in the history of the Jacobite movement. Bonnie Prince Charlie and his army had victoriously marched down through England and were poised to strike at London itself.

Then, at the very moment of their triumph, the Young Pretender and his forces decided to turn back and retreat to Scotland. It was a decision which eventually turned out to be a disaster because it led to their bloody and inglorious defeat at Culloden – the last military battle ever to be fought on British soil.

With the capital in panic at the thought of a Jacobite advance, the prince was determined to press on to try and secure the British throne for his father, the exiled would-be James VIII.

However, his chief lieutenants knew that victory would be no easy matter. As the prince’s forces had marched south, they had not secured territory behind them.

Two of the king’s most formidable military commanders, General George Wade and the Duke of Cumberland, were in pursuit and London itself had a large militia of loyalist troops ready to take the prince on. The sensible thing to do, it seemed, was to pull back. Charles sullenly agreed and, on December 6, 1745, the retreat started.

On his way north, the Scots fought off an attack at Clifton, in the Lake District and left 400 men to garrison the castle in Carlisle.

On Christmas day, Charles reached Glasgow and found he had huge problems picking up support for his cause.

The city was strongly pro-government, and hundreds of its men were fighting on the Hanoverian side against him. Reluctantly – and probably more to get rid of him than anything – Glaswegians did provide Charles with provisions to refit his army, which left 10 days later. By now, Edinburgh had been reclaimed for the king by General Henry Hawley and the Jacobites knew that a showdown was in prospect. Reinforced by the arrival of a further 4000 troops, they finally came face to face with Hawley’s forces at Falkirk. The battle was a disaster for the Hanoverians. They lost ten times as many men as the prince – 400 to 40 – with most of the government forces fleeing the field and leaving behind their artillery and baggage.

Victory at Falkirk, combined with the fact that still more troops and supplies were arriving from France and elsewhere, bolstered the Jacobite army. With government forces continuing to press against him and with the clan chiefs insisting on returning to the Highlands, however, the only way Charles could realistically go was north. He tried and failed to seize Stirling Castle before arriving in Inverness and taking the town on February 18. Fort Augustus succumbed in March, though Fort William held out. By now, there was another problem: the able Duke of Cumberland was in pursuit of the Jacobite forces along with an army of 9000 men. A seasoned and intelligent military strategist – and son of the King – Cumberland would not make the sort of tactical mistake which had allowed the Jacobites to win the battles of Prestonpans and Falkirk.

By April 14, Cumberland was in Nairn, while the prince’s army was only 10 miles west at Drummossie. Charles’s Quartermaster General, John William O’Sullivan, decided that the best approach was to try and catch the Hanoverian forces by surprise. The Pretender’s troops, by then tired out and hungry, marched to Nairn, only to find Cumberland’s forces awake – they were celebrating their leaders 25th birthday. The Highlanders were then forced to trudge back to Drummossie, where they arrived, exhausted and demoralised, just after dawn.

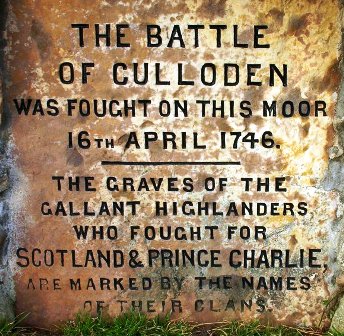

Unknown to them, however, word had reached Cumberland that the enemy forces had tried to pounce on him. Knowing full well how tired and hungry the Jacobites were, he decided to attack them when they were at their weakest. The two sides finally faced each other at Drummossie Moor, better known as Culloden, in a howling, freezing gale, on Wednesday, April 16, 1746. It was, as the prince’s general Lord George Murray observed, a hopeless place to fight a Highland battle.

For the first time during the entire campaign, Charles decided to take personal command of his troops. He was outnumbered from the start – his 5000, ill shod, untrained and hungry men stood against nearly double the number of well-fed, well-equipped Hanoverians. Cumberland positioned his men, who were only about 400 yards away from the Jacobites, in two lines. The first was expected to break when the Highlanders attacked, but the second was carefully laid out three deep to provide massive and continuous firepower.

The battle began with an artillery barrage by the Hanoverian forces. It lasted only a few minutes, but cut down many of the prince’s men before they had a chance to charge. When the charge finally came, despite all Cumberland’s carefully prepared positions, the fierce Highlanders still managed to break through the Hanoverian left flank. It was not enough to overcome the disadvantages of inferior firepower and sheer weight of numbers.

The battle was over in less than an hour and some 750 of the Jacobites lay dead, while only about 360 Hanoverians had been killed. Cumberland had proved to be an astute commander during the battle – but the aftermath earned him the notorious nickname of “Butcher” and ensured that his name would be forever tarnished north of the border.

Determined to stamp the king’s authority on a rebellious people, he let loose his soldiers in slaughter. The wounded were murdered where they lay and any prisoners were shot. A group of men found in a local barn, for instance, were simply locked in and left to burn to death. In all, some 450 people, including innocent bystanders and women and children, are reckoned to have been slaughtered after the battle.

Some Jacobites were luckier – if you could call it that.

They were taken to Inverness, where they were put into jail, churches and even ships. There, many died of their wounds or of the cold. The government was determined to make an example of the leaders of the rebellion. Some – among then Lord Lovat, who had not even been involved at the battle at Culloden – were tried and executed. Others were imprisoned for life.

For Bonnie Prince Charlie, however, there was to be no such ignominy. The flower of the Stewarts had fled the battlefield of Culloden before the fighting had even finished. The hero of the Jacobite rising had become the most wanted man in Britain, with a price on his head that the English imagined would be too large for Scots to turn down.

The fight for the Stewart cause was over forever. The question now was whether the Prince would escape.

The rise and fall of Bonnie Prince Charlie is one of the most remarkable and romantic stories in Scottish history.

But the truth is that the Prince was an arrogant and badly advised loser whose attempt to seize the British throne brought more than a century of misery and poverty to the Highlands.

After Charles’ defeat at Culloden, the British authorities were determined to clamp down on the trouble the Highland clans had caused. They embarked on a policy of repression so brutal and vengeful it is remembered with anger and bitterness in Scotland to this day.

One of their first acts after the battle was to try to catch the Prince himself, who had eluded them by slipping away from the battlefield while the fighting was still going on. However, he remained too clever for them. Charles fled the mainland and made for the Hebrides, outwitting both a massive military cordon and a reward of £30,000 which had been offered to anyone prepared to betray him.

One of the most romantic stories surrounding the Prince was his journey from South Uist to Skye in June 1746. With the islands full of troops looking for him, a plot was hatched to smuggle him from the Hebrides under the noses of the Hanoverian forces.

A local, Edinburgh educated woman called Flora MacDonald was persuaded to help provide the decoy. The Prince was dressed in a blue and white frock and given the name of Betty Burke, with the cover story that he was Flora’s Irish serving maid.

The plot worked – the pair were very nearly seized by troops during their journey but managed to escape without further incident. After landing in Skye, Charles said goodbye to Flora and made his way to the nearby island of Raasay. He then went back to the mainland, moving from Moidart to the even more remote Knoydart and living rough in the outdoors and in bothies.

As summer wore on, the authorities realised they had been outwitted and the hunt for him was gradually scaled down.

The French had sent various rescue missions to try to find Charles and get him out of Scotland. On September 19, they were finally successful. Charles emerged from hiding and boarded the frigate L’Heureux at Arisaig. It was the end of his adventure and of the Stewart threat to the British throne.

While Charles was on his way back to France, then on to exile in Rome, the British forces in the Highlands were busy. Immediately after the Hanoverian victory at Culloden, the Duke of Cumberland – by now bearing the nickname Butcher for his indiscriminate slaughter of the wounded and innocents after the battle – was determined to capitalise on his success and teach the unruly Highlanders a lesson they would never forget.

Cumberland quickly consolidated his position by bringing thousands of British soldiers north. They were allowed to pillage the Highland Glens, raping the women and putting houses to the torch.

The clan chiefs who had backed the Jacobite cause had their castles burned to the ground and their estates seized. Cattle were plundered and taken south, many of them bought by traders from Yorkshire. The plan was clear, to strip as much wealth as possible from the Highlands in the hope that the residents would starve and freeze to death.

Even this however was not enough for some supporters of the Hanoverian cause. In London, parliament debated sterilising all women who had supported the Jacobites. Another suggestion offered was to clear the clans out and replace them with immigrants from the south. These suggestions were not acted on, but the law deliberately changed to suppress the Highland way of life.

Highland dress was banned except that worn by regiments of the British army serving abroad, and anyone found wearing tartan illegally could be executed.

The Hanoverians consolidated their grip on the north by extending their military presence. Field Marshal Wade’s road system, originally built to open up the Highland’s, was extended and military barracks constructed at places such as Fort George, near Inverness.

Back in France, Charles received anything but a hero’s welcome. He was banished to Italy two years after his return and, in 1750, secretly made his way back to London, where he is said to have proclaimed himself a Protestant and had a relationship with a woman he had first met in Scotland called Clementina Walkenshaw, whose sister was housekeeper to the Dowager Princess of Wales. She bore him a daughter, Charlotte. By this time, however, the Prince had lost his charm and become a violent brutish oaf. He beat Clementina so much that she eventually fled from him and, in 1772, he married the teenage Princess Louise of Stolberg. It was an ill fated match – by this time Charles was over 50 and a complete drunkard. After eight years after marrying him, she ran off with a poet.

Charles then invited his daughter Charlotte to share his home and made her the Duchess of Albany. He finally died in Rome in 1788, with the last rite performed by his brother Henry, the Cardinal Duke of York. In his will, he left most of his money to Charlotte – the Scots who had laid their lives on the line for him and the cause he represented didn’t receive a penny.

The Young Pretender’s later life may have been wretched and unworthy, but at least he had money and status. The Highlanders he had used for his futile Jacobite campaign, then abandoned to their fate, faced only hostility and misery from a merciless Hanoverian regime.

With their old bonds to the land and the clan system of rule broken, many opted to leave Scotland altogether. They sailed for the New World, settling in places such as North Carolina and working the land to make a living.

As more and more Highlanders learned about the opportunities available to them in America, the numbers crossing the Atlantic swelled. It was the start of a mass emigration, which was eventually to lead to Scots becoming a powerful force in the establishment and development of the USA. Those who decided to take to the seas for a new life in the colonies included Flora MacDonald, who went with her husband Allan and two of their sons. Flora had been arrested for her part in helping Charles and taken to London, but she had been freed under the terms of a general amnesty and returned to Skye three years later. She went to America in 1774, where ironically her family helped fight for the Hanoverian King George III against rebels who were staging the first battles in what would ultimately become the successful American struggle against the British Crown for independence.

After this, Flora returned to her native Skye, where she finally died in March 1790. During her lifetime, her fame had spread, and thousands of people attended her funeral. She was buried in a sheet which Charles Edward Stewart had slept in during that fateful Jacobite campaign years before.

Flora MacDonald had played only a small part in a campaign which changed the face of Scotland forever. But in death, she maintained her reputation and dignity – which is more than can be said for the man she risked everything to save, and whose vanity and desire for the throne almost destroyed the Highlands.

Leave a Comment