One Sunday morning last year, my friend, Carl Greenwood, and I made the trek from our Orange County, California homes up to Hollywood Presbyterian Church in nearby Los Angeles. We were going to meet Christian author and scholar Dr. Dale Bruner for brunch. Dr. Bruner had agreed to lead the annual retreat that year for the men at our Tustin Presbyterian Church, so we were meeting to discuss the topic.

Dr. Bruner suggested that we come early and attend a class at Hollywood Presbyterian that was led by his son, Dr. Michael Bruner, professor at Azusa Pacific University.

Of all the many church classes I have taken over the years, few stand out in my memory as this one did. Dr. Bruner was teaching a series, and the topic that day was meditation.

Effective meditation is the result of three elements: stillness, silence and solitude.

As Dr. Bruner was preparing the lesson, a Beatles classic, The Fool on the Hill, came to mind, and he found it remarkable that the words from the song hit precisely at what the lesson on meditation was trying to impart.

The song tells the story of a man sitting quietly by himself without speaking to anyone. In other words, he is still, silent, and in a state of solitude. However, though he is perceived as being inane, in reality he is aware of the truly important things that others miss because of the distractions that they let fill their lives.

The song tells the story of a man sitting quietly by himself without speaking to anyone. In other words, he is still, silent, and in a state of solitude. However, though he is perceived as being inane, in reality he is aware of the truly important things that others miss because of the distractions that they let fill their lives.

Now every time this song comes to mind, I am reminded of that class and the need to take time to seek God’s spirit through the meditative practice of silence, stillness and solitude.

We live in such a busy world, with countless diversions, that it can be hard to find a quiet time to be still and let God speak to us.

A number of years ago, I was introduced to Celtic Spirituality by Dr. Rebecca Prichard, currently a New Theological Seminary of the West professor. At that time, Rebecca was pastor at Tustin Presbyterian Church, and she invited Dr. John Phillip Newell to give a lecture there on Celtic Spirituality. Dr. Newell had been warden at the abbey on the Isle of Iona in Scotland, known as the birthplace of Celtic Spirituality. Rebecca asked my wife, Loretta, and I to host Dr. Newell for the night at our home.

I was up early the next morning to prepare a simple breakfast for Dr. Newell and myself. As we ate, Dr. Newell commented on how he appreciated the peaceful setting, with the view of the hills and valley out our window. His practice was to arise early in the morning for a time of quiet reflection and devotional.

Dr. Newell left with us a copy of his book, Listening for the Heartbeat of God. The title is taken from the scene at the last supper, as described in John 13:23 – Now there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved. One can visualize the disciple John listening at Jesus’ chest. We are encouraged to seek God’s presence, God’s heartbeat, everywhere.

I used to be puzzled by this depiction, since when looking at the painting of the Last Supper John is leaning away from Jesus. When I was in Milan recently, and privileged to see Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece in person, this fact was confirmed. However, a guide pointed out that the painting was just a single moment in time, and just not the same exact moment that is referred to in the scripture.

I am part of a men’s breakfast group that has been meeting on Friday mornings since 1980. Recently we studied one of Newell’s newer books, The Rebirthing of God: Christianity’s Struggle for New Beginnings. I think a better title would be, The Rebirthing of God in Us, since God does not need rebirthing. We do.

Using different objects from Iona as symbols for each chapter, Newell discusses various aspects of reconnecting. One of those is reconnecting with spiritual practice. Newell uses the remote location of Hermit’s Cell on Iona as the symbol. Here St. Columba would come in the 6th century to meditate. Newell also mentions other forms of spiritual practice, including walking a labyrinth and yoga.

When I entered semi-retirement, Loretta convinced me to take a yoga class with her on Tuesday and Thursday mornings. Along with various positions and exercises, there are moments at the middle and end where there is quiet time when the mind is cleared for sole, silent, still contemplation. While these are perfect occasions to let the Spirit come in, I have to admit that I often find myself taking those moments to plan the rest of my day. Having a type “A” left brain, task-oriented persona, I still have a long way to go to fully reach a complete meditative state in those sessions.

Dr. Newell points out that the term, yoga, is derived from the Sanskrit, meaning a desire to be yoked with the sacred. At the end of each yoga class, we stretch out our arms, and bow our heads to each other as we say, “My soul bows to your soul, Namaste.” Namaste actually means “the divine in me bows to the divine in you.”

Dr. Newall also refers to Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk, who followed a discipline of silence. For Merton, “spiritual practice is not seeking “to know about God, but to know God…seeking the experience of presence.” Or as noted psychoanalyst Carl Jung put it, “I don’t need to believe. I know.”

Merton used a threefold pattern for spiritual practice: 1) remembering our diamond essence, 2) remembering the diamond essence in everyone and everything, and 3) accessing the diamond essence of our being in order to be strong for the work of transforming the world. For Merton, the diamond essence referred to the image of God.

Celtic spirituality focuses more on experiencing God in our lives as opposed to ascribing to a set of doctrines.

As Dr. Newell puts it, “Western Christianity…had confused faith with a set of propositional truths about the Divine, rather than a personal experience of the Divine that could be undergirded and sustained by particular practices and disciplines.”

This perspective has helped me overcome decades of guilt over the rigid, literal beliefs of the Fundamentalist church I attended during my high school years.

The Celtic approach is also evident in the book, Rethinking our Story, Can We Still be Christian in a Quantum Era? by Doug Hammock, pastor of North Raleigh Community Church in North Carolina. The author affirms that “Celtic Christians honored diverse ways of experiencing God…Celts focused on divine image breathed into us at creation…By integrating meditative technique with our approach to scripture, we become more discerning…Christian tradition offers a spirituality deeper than learning, deeper than doctrine.”

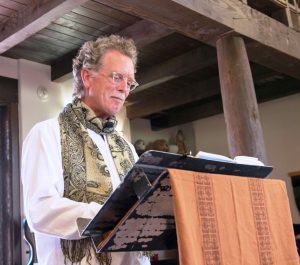

If only in my high school years I had a pastor like the Rev. Dr. Gary Demarest, renowned Presbyterian minister and church leader. He was honest enough to say, when giving a seminary board meeting devotional a few months ago, something like, “I believe in Jesus and the resurrection, but after all these years I still can’t answer the question: What if when I die, it all just turns black?”

We can have faith amid our doubts. As theologian Paul Tillich once said, “Sometimes I think it is my mission to bring faith to the faithless, and doubt to the faithful.”

As a final example, I would like to share from the Preface to my new book, From Ledgers to Ledges; Four Decades of Teambuilding Adventures in America’s West. I am a big fan of John Muir. Muir and I have some things in common: like Muir, I am part Scottish, love the outdoors, am Presbyterian, went to the University of Wisconsin, headed west, hiked parts of the Muir Trail, and am a member of the Sierra Club, co-founded by Muir. Nevertheless, I could not hold a candle to all that Muir did for the American West.

Muir was hiking one time in Alaska with Stephen Young, a missionary to the native Indians, who wrote a book about the experience titled Alaska Days with John Muir. They were camped at the base of a mountain in Glacier Bay.

As recalled by Young after a rainy night, Muir’s gaze upon a mountain brought this breathless exclamation: “‘God Almighty!’ he said. Following his gaze…I saw the summit highest of all crowned with glory indeed…As we looked in ecstatic silence we saw the light creep down the mountain…Our minds cleared with the landscape…But there was no profanity in Muir’s exclamation, ‘We have met with God.’ A lifelong devoutness of gratitude filled us, to think that we were guided into this most wonderful room of God’s great gallery… ‘We saw it! We saw it. He sent us to his most glorious exhibition. Praise God from whom all blessings flow.’” ~ Story by Gerald Herter

Leave a Comment