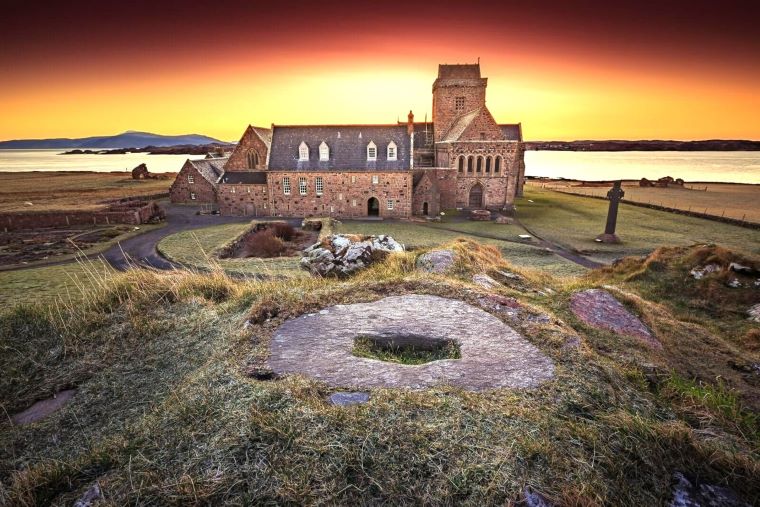

There is a landfall off the coast of Argyll in Scotland that deserves to be the jewel in the crown.

While many cross to Iona each year to visit the island where St Columba made his home and his monastery, the island that became a place of pilgrimage for composers, writers, and princes and, later – for everyone else – isn’t the site that I am referring to above.

The holy islet that I believe to be every bit as imporant and special is visited by almost no-one. In Gaelic, the name of the island is Eileach an Naoimh, pronounced Ailach an Nerve. I translate that as the Holy Islet. It is certainly small enough: a mile long and nothing like as much across.

What we do know for certain is that St Brendan came here from Ireland (about 542 AD) to build a monastic settlement – some twenty years before Columba arrived with his followers on Iona. Here are the only beehive cells in Scotland, all remarkably well-preserved. They are shaped like giant beehives and built with boulders, and it is still possible to hunch under their lintels and go inside. These stone shelters would have housed the pilgrims who visited. There is a tiny stone chapel too, and a strange underground cell that might have served as a place of penance. St Brendan, known as the Navigator, and famous for his voyages, chose this site wisely; on the islet’s east side, shielded by the little hills that surround it, the place is perfectly protected from the Atlantic storms.

The Celtic Christians of the 6th and 7th centuries had a place of retreat that they called Hinba. That translates from the early Irish Gaelic as the notched island. And in the blink of an eye we hit the great dilemma when working out precisely the locations early scribes are referring to: they used different names. Of course all manner of academics have writen theses about the possible location of the mythical Hinba, the notched islet. Some have argued it was Oronsay off Colonsay, and there are others who think it was out in the Uists; one or two have contended it was in among the Clyde islands. Part of the difficulty arises from the name and its meaning: where on earth do you find an island that doesn’t possess a notch? Finding one that does is hardly a struggle. The fact remains there are plenty (perhaps more than any others) who believe that Eileach an Naoimh must have been Hinba. For those early Celts crossing the narrow stretch of water between Ireland and Iona it lay almost perfectly midway. And the names given to specific locations on the islet make very clear how significant it must have been: the well is dedicated to St Columba, and other locations to Brendan and Brigid. St Columba’s own mother is reputed to be buried here. At first the idea of that seems odd: why on earth would she have been brought across from Ireland to this place? Obviously it points to the fact that it was considered holy ground.

The early Celtic Christians didn’t think in terms of Ireland and Scotland – in those days it was as though one simply landscape flowed into the other.

And when you study any map showing the north coast of Ireland and the west coast of Scotland that suddenly makes every sense in the world.

Hinba, the notched islet, was an important place of retreat to those early Celtic Christians. It is mentioned several times in Adomnan’s Life of Columba: the saint visited often enough. Perhaps Iona became too busy with excited chatter and Columba was forced to flee. And if it was indeed Eileach an Naoimh he visited then it was here he had a powerful vision where he was struck by an angel and left with the scar of the blow for the rest of his life.

It was a profoundly powerful experience visiting the islet. Let me give you a more exact sense of where it lies, of the view we had from that sheltered place on Eileach an Naoimh’s east side. Straight east of us again lay the very northern tip of Jura: a bulbous head of land studded with a jagged melding of cliffs and caves. And to the north of that lay Scarba with its single great hill: in between the two of them the great Corryvreckan whirlpool. Coming north again from there the much lower-lying islands of Luing and Seil.

It was my wife Kristina who remarked that it was somehow as though the monks might have left early that morning and would be back in the evening. Perhaps it was only later the words resonated with me so profoundly and I came to think of Iona, the island I’ve known and loved so deeply since early childhood. Somehow I feel a very deep sense of history on Iona, of the past. Perhaps it was the realization that we must be looking at tiny fields on Eileach an Naoimh that so reinforced the whole sense of timelessness. There in front of us as we sat close to the beehive cells on that perfect afternoon were without any doubt ancient fields that must once have been created and cultivated by the monks in between those rough slabs of low-lying stone. Somehow that rendered it a truly living place, that somehow couldn’t have been left long ago. It played tricks with the mind.

Later I went off exploring on my own. More than anything I wanted to get up to the island’s heights and to have a proper sense of where I was in relation to the broken jewellery of other islands about me. The views west to Mull were staggering; I imagined the journey those early Celtic Christians must have made from Iona as they came by curragh along the sheltered south coast of Mull and then into the Garvellach islands (there are effectively four of them, Eileach an Naoimh being the fourth and the one lying furthest to the south). But when I stood at that highest point of the islet I realized something else. I was looking steeply down to the sea on the other side of the islet; looking down a deep gully that extended hundreds of feet from where I was standing to the western edge of Eileach an Naoimh. It was a great gash that ran from top to bottom, almost as though the islet had been struck by lightning and the resulting scar left for ever written in the rocks. And the name Hinba came back to me: the notched islet. Here surely was the notch they had known, that had given the place its name.

Leave a Comment