WALES DAY 4; Wildflowers

Like many nations, the history of Christianity in Wales is quite complex.

Like many nations, the history of Christianity in Wales is quite complex.

Druids and Celts ruled the religious roost here until the Roman conquest in the 1st century AD. Rome’s conversion to the monotheism of Christianity under Constantine the Great was slow in reaching the empire’s westernmost outpost, and it was not until after they had departed permanently in 383 AD that ‘the way, the truth and the light’ found firm footing in the country.

In the centuries since, foreign kings, armies, cultures, bishops, merchants, preachers, and more have come and gone, but the seeds of that early Christian faith, scattered and sown mostly along Wales’ western coastline, bloomed like wildflowers.

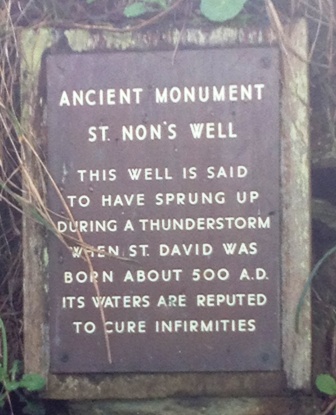

The Chapel of St. Non is nestled along the newly-named Celtic Sea (formerly the Irish Sea) in Pembrokeshire, in the southwest corner of Wales. It is the birthplace of the country’s patron St. David. It is also a homage to his mother Non, or Nonna, who lived there in the 5th century. The small ruins are considered the oldest Christian site in Wales, and are accompanied by a shrine, a Celtic Cross, and a holy well. Many devout Christians from around the world still make the pilgrimage to St. Non, throwing coins into the well waters in exchange for blessings.

St. David, who died in 589 AD, founded a monastery nearby. There, a massive Cathedral in his name was constructed alongside his original house of worship in 1181, and still welcomes worshipers today.

A well-preserved 11th century Celtic Cross stands over the tiny town of Carew a short distance away. Early Christians thought to include the circle – a Celtic symbol for the sun, moon and wholeness – as a way of slowly integrating Celts into their religious fold.

Further up the country’s western coastline, northeast of Newport, sits the Parish of St. Brynach. Originally a 6th century Christian ‘ecclesiastical center’, the building was renovated and expanded by the Normans six hundred years later. A number of the church’s original artifacts have survived, however, including the 10th century Nevern Celtic Cross, as well as a once free-standing 6th century Celtic Cross, which has since been cemented into the walls of the edifice.

Further up the country’s western coastline, northeast of Newport, sits the Parish of St. Brynach. Originally a 6th century Christian ‘ecclesiastical center’, the building was renovated and expanded by the Normans six hundred years later. A number of the church’s original artifacts have survived, however, including the 10th century Nevern Celtic Cross, as well as a once free-standing 6th century Celtic Cross, which has since been cemented into the walls of the edifice.

Interestingly, the ‘kneelers’ – small cushions which are used by parishioners today in the pews during prayer – are hand-woven by area womem, highlighting a host of knotted designs, a nod to the area’s Celtic past.

Outside in the courtyard, Yew Trees – once used as symbols of immortality by Celts – give shelter to aging tombstones and walkways. One tree – ‘The Bleeding Yew’ – has been dubbed as such as it leaks red sap – the colour of blood – at various times through the year. Many still believe it to be a sacred space with healing properties.

And while the nearby Neolithic burial ground of the Pentre Ifan Dolmen predates Christianity in the area by 3000 years, local priests – perhaps sensing some sort of spiritual hotspot – regularly sought divine inspiration from the hilly locale, as well as from other, similar surrounding sites.

And while the nearby Neolithic burial ground of the Pentre Ifan Dolmen predates Christianity in the area by 3000 years, local priests – perhaps sensing some sort of spiritual hotspot – regularly sought divine inspiration from the hilly locale, as well as from other, similar surrounding sites.

A few miles north and inland, at the confluence of the rivers Teifi and Afon Dulas, the town of Lampeter is awash in a sea of aging churches, monasteries and religious study centers. Once the stronghold of faith in western Wales, the area has secularized into an educational hub over the last century.

Similarly, all of Wales has undergone a transformation of spirit in recent years. While churches continue to sit squarely at the core of most towns and villages here, attendance is down significantly with each passing generation. And though a third of the population still identifies themselves as Anglican (Church of Wales), and another third still call themselves Catholic, a growing number now consider themselves to be ‘non-conformist’, with a good percentage of those saying they have ‘no religion’.

It is of interest to note the emergence of two sacred movements in Wales today – Neo-Druid and Neo-Celtic – each ready to bloom like wildflowers. In search of deeper meaning in their lives, many Welsh are returning to their ancestral roots – spiritual seeds that were scattered and sown long before Christianity.

Leave a Comment