Though unknown to most, Irish scribe Oscar Wilde thrived in his role as an environmentalist.

He agitated for a healthy as well as a beautiful environment in all spheres, not just in one’s choice of private life, but in education, dress, cities, and in the areas that today we generally reference by the term environmentalist. This article will look at his track record in that final category.

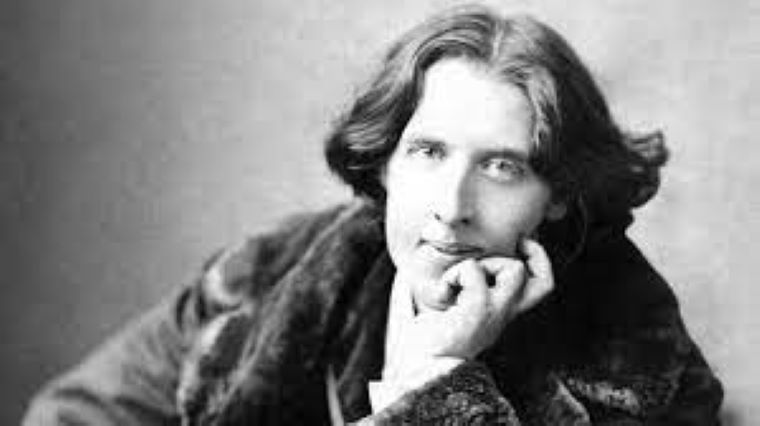

In 1882, Wilde, fresh out of Oxford University with a gold medal, tall, dressed in silk stockings, and having published a first volume of poetry, delivered a year-long lecture tour of the United States and Canada. His expenses were paid, and he had a contract for a share of the profits, if any. He spoke on “The Decorative Arts,” “The English Renaissance in the Arts,” and “The House Beautiful.”

However, in his lectures and in many newspaper articles he also expressed his concern about the pollution of American, English and Canadian skies and rivers.

For instance, on January 7, 1882, as related by a reporter for the Philadelphia Press, “As the train neared Philadelphia, Wilde again grew distracted and depressed by the scenery. Whitman and other poets, he said, had always been ahead of science, at least conceptually. Now he wondered, ‘Why does not science, instead of troubling itself about sunspots, which nobody ever saw, or, if they did, ought not to speak about – why does not science busy itself with drainage and sanitary engineering? Why does it not clean the streets and free the rivers from pollution? Why, in England, there is scarcely a river at some point is not polluted: and the flowers are all withered on the banks!’”

Oscar grew up in a family with two super-achieving parents. Today a plaque at One Merrion Square, Dublin, Ireland, reads: “Aural and ophthalmic surgeon, archaeologist, ethnologist, antiquarian, biographer, statistician, naturalist, topographer, historian, folklorist.” This celebrates Oscar Wilde’s father, Sir William Wilde, a Gaelic and English-speaking eye and ear surgeon who collected fairy tales rather than fees from Irish cottagers.

Oscar’s mother, Lady Jane Francesca Wilde, her “hair as blue-black as a raven’s wing,” was an award-winning translator, translating books from the French and German as well as Driftwood from Scandinavia. In fact, Oscar was initially known as her son. He had to work awfully hard for her to become known as his mother.

Lady Wilde explained her second son’s names thus: “He is to be called Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wilde. Is not that grand, misty and Ossianic?”

The names Oscar and Fingal are Gaelic and O’Flaherty recalls the Galway heritage of his father. Papa Wilde, the eminent scientist, was descended from the O’Flyns of Connaught and the Finns of Cong, County Mayo.

Oscar had very much an outdoor childhood in Galway, where his father bought land and built a summerhouse with magnificent views of Lough Corrib and its 364 islands, (365 in leap years!). As boys, Oscar and his older brother Willie often accompanied their father during his explorations in the west of Ireland. They sketched caves, cairns, monoliths, stone circles, and holy wells. There was fishing and hunting.

On Oscar’s lecture tour (He gave 140 lectures in 260 days, to every level of society, from aristocrats to miners, from college boys who tried unsuccessfully to discountenance him to lacrosse-playing Canadians) his receptions were varied both from the people and the press. Often the media acted as if he were fair game to be shot down. Some reporters, of course, could see beyond his amusing costume. The San Francisco Chronicle noted that the visiting lecturer “could not only talk of the matter of fact when he pleased like a man of education and refinement, but like a man who was capable of deep thought and vigorous conclusions.”

Wilde was not uncritical himself. He was especially so of Chicago. Knowing the millions of dollars poured into the city to rebuild it after a great fire, he stated, “I was surprised by its poor architecture. There are no artistically beautiful buildings in the city.”

When he left the town, a reporter wrote, “Go, Mr Wilde, and may the sunflower wither at your gaze.”

Always he had fun. To an audience of miners at Leadville, Colorado, he explained how the great Renaissance sculptor Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571) had cast his Perseus with its severed head of Medusa. The miners wished he had brought Cellini along with him.

“Unfortunately, he’s dead.”

“Who shot him?” they asked, and then took Oscar down a mineshaft for dinner – whiskey. For all his sensitivity he could throw back booze with the best of them. Furthermore, he was noted to enjoy, amongst the lilies, sunflowers and embossed slippers, “a big steak dinner, smothered in mushrooms, a dozen raw oysters, extra dry champagne…”

Wilde never talked down to his audiences. He was inherently friendly himself, a very good-humored man. Like a druid magician, he preached, “‘We do not want the rich to possess more beautiful things, but the poor to create more beautiful things, for every man is poor who cannot create. We want to see you possess nothing in your house that has not given delight to its maker, and does not give delight to its user; we want to see you create an art made by the hands of the people, for all art to come must be democratic.’”

For furniture, Wilde recommended the Queen Anne style, with polished brass and mahogany borders. Flowers, blown glass, Greek statuary, old china and traditionally bound books completed his vision of household furnishings.

He visited art schools. Numerous craft centers, sculpting studios and art academies sprung up in his wake – “and untold artists, male and female, took personal inspiration from Wilde’s message and example. As both a lecturer and a celebrity, he had made an indelible impression wherever he went, alternately shocking, amusing, entertaining, and enlightening thousands of post-Civil War-era Americans at a time when they were sorely in need of each. It had been a brave, even gallant, endeavor.”

“Crossing Dayton’s Miami River, he repeated his ecological message, speaking approvingly of Indian place names, then gave the city fathers a piece of advice that might have carried over, with profit, for the entire industrialized East: ‘You should never let your manufacturers pollute the air with smoke.’”

Wilde visited eastern Canada twice that year, lecturing in major cities like Ottawa, Montreal, Toronto, Quebec, as well as smaller places: Kingston, Halifax and towns in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island – often to capacity audiences and very much taking part in Canadian life, attracting favorable and occasionally hostile attention from the press.

At first Oscar had reservations about the design of Niagara Falls as “lacking in grandeur and variety of line” but ultimately declared, “that the water was ‘full of changing loveliness.’”

At Montreal he found a billboard with his name in six-foot-high letter in atrocious primary colors but considered it a kind of fame.

“In Ottawa, the Canadian capital, Wilde continues his criticism of local flora, looking askance at the lumber mills releasing black smoke into the sky and sawdust in the Ottawa River….”

He said: “The things of nature do not really belong to us. We should leave them to our children as we have received them.”

In Montreal he thought, and said, “the modern bonnet keeps off neither sun in summer nor rain in winter.” In contrast he had found nothing more graceful in the world than the broad-brimmed hat of the Rocky Mountain miners.

In Toronto, wearing his black western sombrero, Oscar sat in the Lieutenant Governor’s box enjoying a lacrosse match at City Stadium between Toronto’s home team and the St. Regis Indians from nearby Cornwall Reservation.

He said, “Oh, I was delighted with it. It’s a charming game.”

He was particularly taken with Ross McKenzie, the leading lacrosse player in Canada, whom he described as a “tall, finely built defense man. I admired his playing very much.”

However, he paid equal attention to ladies’ dress.

He returned to Canada in October and lectured at the Ontario Peninsula townships of Brantford, Woodstock, and Hamilton. In New Brunswick, he visited the Six Nations reservation as well as a cabinetmaking factory and the Wesleyan Ladies’ College. At St. John, “Local boatmen on Grand Lake renamed one of their vessels the Oscar Wilde in his honor.”

The Canadian lectures were a great success and “Feeling himself ‘greatly improved in speaking and in gesture’” back to New York he went to rest and recuperate.

Leave a Comment