The final scene of Kenneth Branagh’s 2021 cinematic masterpiece Belfast might be one of the most moving and memorable moments in modern movie making; after Granny (Judi Dench) says goodbye to her son (Jaime Dorman), his wife (Catriona Balfe), and their children (Jude Hill, Lewis McAskie) as they board a bus bound for a new life across the water, she walks home, stopping to take one last, lingering look. As the film fades to black, words appear on the screen;

For the ones who stayed.

For the ones who left.

And for all the ones who were lost.

Perhaps an epitaph for the past, or a eulogy for troubled times, Branaghs’s black and white coming-of-age tale – which is set in the late 1960s – is both an homage to his hometown and one last, lingering look over his shoulder.

And though the film has garnered great popular and critical acclaim since its release last November (including an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay), the director – who grew up in the city’s Tigers Bay area as the son of working-class Protestant parents – has insisted in interviews that, while Belfast was a movie that he had to make, it was time for him to move on.

The implications to residents of his hometown were obvious – it is time to move on.

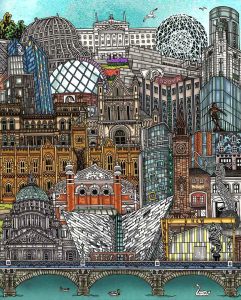

However, as much as Belfast – and all Northern Ireland – keeps one foot to the floor for the future, it has the other firmly planted in the past. As such, and instead of ignoring its history – or weeding it out altogether – the city continues to bloom atop its rich and robust roots, reimagining and reinventing both its scenery and its storylines.

Restored

Nowhere is this replanting more evident than in Belfast’s famed Linen Quarter, where old-world charm meets new-world charisma.

Situated just south of City Hall, only a few blocks from both railyards and shipyards, the heritage district was the hub of the world’s garment industry from the late-1700s to the mid-1900s. After WWII, rising costs, the advent of synthetic materials, and foreign competition signalled a period of decline. In recent years, however, the area has undergone an overhaul as new industries and investments have moved in and refit the aging brick-and-mortar buildings, giving them – and the city – both a much-needed facelift and a lift in faith.

As a result – and aided by the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that ended decades of sectarian division – the once-wilting borough has blossomed into a major global business destination over the last twenty-plus years, boosting Belfast’s economy. The growth of the city’s commercial sector has seen much-needed funds funneled into housing, hotels, restaurants, pubs, shops, entertainment, events, and more.

“Everything used to just close right up around here during the summer months,” says Bronagh Smith, manager of the casual/chic Meat Locker restaurant on Howard St. “In the past 20 years or so – even during the COVID-19 pandemic – the streets have been filled with people. And not just tourists, students, and workers from other countries, but many Irish from other counties as well. We’ve become the Celtic Tiger of the North.”

Refined

Part of the attraction is the upscale culinary culture.

“We have come a long way, quite quickly,” notes Smith’s boss Chef Michael Deane, who returned home to Belfast in the mid-1990s and today owns and operates five restaurants in the city, including the Michelin-starred Eipic.

“At one time it was all just fish ‘n’ chips and chowder, but now we have an incredible variety of world-class cuisine, much of which is produced locally.”

“And, as eaters have upped their standards and demands, we have had to up our game also. The shift in people’s palates has been quite dramatic.”

Ryan Stringer agrees.

“What we are doing now was unheard of just a few years ago,” shares the chef of James St. restaurant. “And not just with regard to food, but also with our understanding and appreciation of spirits as well. Guinness and Jameson’s will always be a part of our liquid landscape, of course, however we now produce all sorts of craft spirits and creative cocktails, and the city’s wine culture has evolved significantly.”

Evidence of that refinement is on display at Coppi, one of several elegant eateries located by the city’s magnificent Metropolitan Arts Center.

“Oh, we are pretty much regulars here,” says 24-year-old Liz Keller, sitting with a table of girlfriends. “It is quite contemporary – the food is fantastic, the drinks are delicious, and the ambiance is amazing.”

Like Keller, many of the diners are young, well-dressed, and well-versed in culinary matters.

“In the past few months, we have tried dishes from all over the world right here in Belfast – Italian, French, Spanish, Greek, Polish, Turkish, Korean, Thai, Cuban, Columbian, African. It has been an education for sure.”

“And the nightlife is brilliant,” she continues, looking around the room. “There is real joie de vivre here now; restaurants, pubs, clubs, music, theater, festivals…it’s very exciting!”

“We still have a way to go,” admits Michael Deane, “both with our culinary offerings and as a city in general. However, at least we are moving in the right direction.”

Recreated

Belfast’s creative class is certainly moving forward, enjoying a cultural renaissance it hasn’t seen since the early 1900s.

Along with a bevy of world-class restaurants, concert halls, live theatre venues, festivals, art galleries, bookshops, and the like, the city is home to a thriving underground arts scene.

In particular, the quirky and quaint Cathedral Quarter is awash in funky cafes, used record stores, bookshops, boutiques, pop-up shops, tattoo parlours, salons, speakeasys, and more.

“I have been here for almost six years,” shares Ken McNeely, owner of Young Savage, which specializes in vintage clothing and alternative paraphernalia. “This area has grown quite significantly since I first opened. It used to be sort of our little secret part of the city, but that’s not the case at all anymore.”

“It has become a bit of a hipster hotspot,” laughs Aoife Downie, a Fine Art graduate from Ulster University. When you go down there now, it’s all young people with beards and tattoos and piercings. It certainly makes the city more interesting and colourful.”

On cue, she points to the variety of vibrant graffiti that adorns the sides of many of the neighbourhood’s buildings.

“It’s great to see the growth and to have all of these new businesses and buildings,” she smiles, adding that she intends to stay and work in Belfast, “but someone has to make them beautiful.”

Like Downie, local artisan Alison McBride has chosen to make Belfast her permanent residence.

“There was a time when I seriously considered leaving and going to London,” admits the 48-year-old craft-jewelry maker from her stall at nearby St. George’s Market. “My husband and I simply couldn’t make a proper living doing what we love here. That has all changed.”

Built between 1890 and 1896, St. George’s Market remains the beating heart of the city, bustling with thousands of visitors each weekend.

“For one thing, there are more jobs here now,” continues McBride. “More jobs means more disposable income for local people. On top of that, we have seen greater amounts of tourists in recent years.”

Revisited

Revisited

Despite the difficulties brought on by COVID-19 and the ongoing uncertainty of Brexit, tourism in Belfast is expected to rebound in 2022, with millions of guests bringing travel numbers back to pre-pandemic levels. Fittingly, given the region’s strong nautical heritage, many of them will arrive on one of the 130 cruise liners due to dock in the city’s harbour.

There, it is only a short stroll to Titanic Belfast, the city’s premier museum and one of the most popular tourist attractions on the planet.

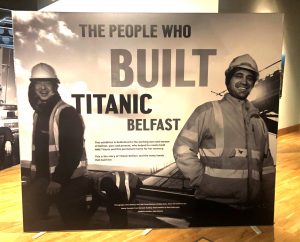

Opened in March of 2012, the iconic six-floor building – which features nine interpretive and interactive galleries – recently celebrated its 10th anniversary with a number of events, including a special photographic exhibition titled ‘The People Who Built Titanic Belfast’ featuring 123 photographs and illustrations telling the story of the iconic building from its inception and design to the structure being fitted and built.

Over the last decade, the facility has welcomed more than six million visitors from over 145 countries and was crowned the World’s Leading Tourist Attraction in the 2016 World Travel Awards.

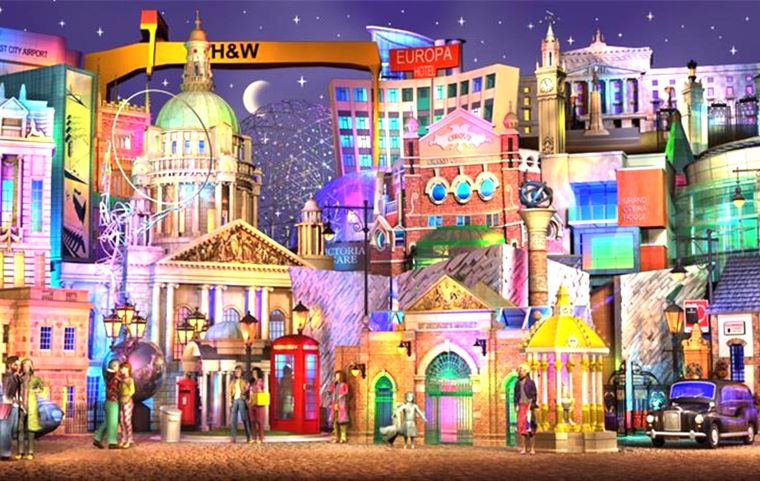

Titanic Belfast is part of the area’s “Maritime Mile,” which includes an array of attractions, exhibitions, historic buildings, public art, and even a Glass of Thrones Trail – a series of six stained-glass installations which celebrate Northern Ireland as the home of Game of Thrones.

“We are huge, huge fans of the show,” notes 26-year-old Pierre Mouliot who, along with his fiancée Monique, are visiting from Paris. “This is our first time here, and we came specifically to see all the Game of Thrones sites. Before the show, I couldn’t even have told you where Belfast was on a map.”

Nicknamed “Thronies” by locals, fans of the blockbuster HBO series – which ran for 73 episodes over eight seasons from 2011-2019 – can enjoy a full-gamut of GOT experiences in Belfast, and across Northern Ireland, including touring filming locations and immersing themselves the new, multi-media Game of Thrones Studio Tour in nearby Banbridge.

“We have only been open a couple of months, but we are already seeing heavy traffic,” explains Alex McGreevy, the facility’s Public Relations and Communications Manager. “People are coming from all over the world. It’s great for the local economy, and Northern Ireland as a whole.”

While Belfast and its environs have long been a cinematic hotspot, the popularity of streaming services has upped the ante; smash-hit series such as Line of Duty, The Fall, and Derry Girls were all filmed in and around the Northern Irish capital.

“After watching Game of Thrones, I became very fascinated with the culture here,” says Pierre Mouliot. “I started exploring other television shows, then movies, blogs, books, records, and lots of stuff online. And I discovered the sounds of Van Morrison.”

Revered

Along with their Game of Thrones excursions, Moirot and his bride-to-be have numerous other adventures awaiting them in Belfast, including stops at local museums, a night at the Grand Opera House, and a trip down the Van Morrison trail.

The Belfast Bard, the Mystic of the East…Morrison has been called many things since first emerging on the city’s music scene in the mid-1960s – not all of them pleasant. A notorious curmudgeon and recluse, the songsmith has nonetheless spoken highly of his hometown on many occasions.

“Belfast is my home,” he shares via his website. “It is where I first heard the music that influenced and inspired me, it is where I first performed, and it is somewhere I have referred back to many times in my song writing over the past 50 years.”

Just as Van Morrison’s music provided the bittersweet soundtrack to Branagh’s Belfast, so his work has informed and inspired music lovers for more than half a century. Long time listeners and those new to his tunes will cherish the chance to walk in his footsteps – literally.

Launched in 2014, the self-guided 3.5-kilometer Van Morrison Trail begins at Elmgrove Primary School, before winding its way through the nearby Hollow, along the Beechie River, by the bard’s childhood home on Hyndford Street, around the neighbourhood where he held his first jobs, past Orangefield Park and High School, by the now-defunct Belfast & County Down railway station, up Cyprus Avenue, past Saint Donard’s Church, before coming to a close at the former site of his favourite eatery Davey’s Chipper.

Drawn from memory, Morrison has referenced these places repeatedly over the course of his prolific career. during which time he has written and recorded more than 40 studio albums. It is no wonder that he is revered by both fans and critics alike.

“When you find an artist, a writer or a musician who has been creating for decades, it feels like you’ve discovered a planet that you’ll spend the rest of your life exploring,” writes Northern Irish author Darran Anderson. “Van Morrison was never a polemic figure. He no doubt understands that explaining his music is like undertaking a live autopsy, which partly explains his caginess with interviewers. He didn’t set out to defy the either/or binary of Northern Ireland. He didn’t need to explain that you can be both an East Belfast musician and an Irish poet (and vice versa). He just did his own thing and thus embodied a different way of being and showed us another way forward, or rather many ways. And perhaps he tired of all this talk of the past. He’s an artist who has always moved on. So, he’s moving on. And so – if our luck, empathy, and spirit hold out -are we.”

Reflected

Just west of the downtown core, the Falls Road area remains the city’s core Catholic enclave. I stop in at a small, non-descript café for breakfast, noting with interest that, here, the “Ulster Fry” is called an “Irish Fry.”

A group of four young men come in and sit next to me. They are in their late teens, each attired in jeans, hoodies, ballcaps, bling, and expensive Nike shoes. They are upbeat and pleasant. They introduce themselves – Kevin, Timothy, Ronan, and Liam.

“You’re from away?” Kevin asks me, detecting my accent.

“Canada,” I answer

“Do you know Drake?” asks Ronan, referencing the Toronto hip-hop star.

“We’re on a first name basis,” I reply, with a wink.

“Does he have a second name?” he queries with a smile, and the room erupts in laughter.

We chit-chat for awhile, before the Kevin tells me that he has relatives – an aunt, uncle, and cousins – in Mississauga, outside of Toronto. I inquire about them.

“They were from the Divas Flats,” he recounts. “They left here years ago – they’d had enough of the Troubles. Their kids were born in Canada. I was over to visit with them before COVID. Bloody cold over there!”

I smile knowingly, before asking them about the Troubles.

“Ah, that’s done with,” says Timothy, adding, “before our time.”

“Well, maybe not totally over, y’know?” pipes in Kevin. “There are still some idiots out there, but it’s not really a part of our lives, y’know? I don’t know anyone that’s involved with that crap. Maybe my parents would have known a few people, but it’s not really discussed, y’know?”

Outside, the colourful political murals are reminders of past struggles, as are the traditional Black Taxis that weave their way through traffic.

Nearby, at the Peace Wall – the concrete divide that separates the Nationalist Falls Road from the Loyalist Shankill Road – a group of American tourists emerge from a minivan. Black and red markers in hand, the sign their names on the wall.

Their driver, a young man from Ballymena, just northwest of the city, smiles and hands me a marker.

“First time here?” he asks.

I tell him that I have been to Belfast several times, going back to 1989.

“Ah, it’s not the same city,” he notes. “Even here, in this neighbourhood, it’s completely changed. It may not look like it, but the attitudes are very different than before.”

I ask about the murals and the Peace Wall.

“We don’t really see it as propaganda anymore…it’s more just like street art now. It’s a huge draw though…visitors are really fascinated with this stuff. I mean, who can blame them, really? For years the only news you got out of Northern Ireland was bad news, and this area was at the center of it all.”

As in the Falls Road district, “political tourism” is alive and well a few blocks over on the Shankill Road, where Union Jacks still fly, portraits of Queen Elizabeth II fill store-front windows, and historical frescoes tower over corner lots.

“That’s just for show, mostly,” shares Claire, a 20-year-old waitress who was born and raised in the community. “Young people, like myself, don’t give a shite about that stuff to be honest. I’ve got a lot of friends from the Falls. We go dancing and drinking downtown each weekend. We never discuss politics. Not because it’s taboo or anything…it’s just that we don’t really care.”

Despite an upcoming election for the Northern Ireland Assembly (as of this writing, Sinn Fein were leading in the polls), young people here – as elsewhere – have other things on their mind.

“I’m in university, studying psychology,” continues Claire. “Afterwards, I’d like to stay here and find a good job – you can do that now. Maybe travel a bit before settling down. I’d like to have a family, maybe two or three children. I have to find a husband first though! You know any good, single Canadian boys?”

Like Kevin, Timothy Ronan, Liam and most others their age from Belfast, Claire has only known peaceful times. Their perspective is mostly one of indifference to, or intolerance of, matters of division.

Revealed

While the Troubles may have brought out the worst in people from the two communities over three decades, it appears that peace has brought out the best in them.

“What you have in Belfast, and Northern Ireland, is nothing more than two sides of the same coin,” says Michael Doherty, who, at the age of 61, has been driving a cab in Belfast for 40 years. “We’re the same people, for Christ’s sake, from the same stock!

“You see, once we had put down the guns and started talking and listening with one another, I think we saw how foolish it all was…and that we had more in common with one another than we thought. What we are starting to see now, I believe – and I get this from talking with my own grandchildren (ages 20, 17, 15) – is that Belfast is no longer an ‘English’ city, nor is it an ‘Irish’ city – it is its own place, with its own unique identity.”

Interestingly, and to Doherty’s point, the most recent census for Northern Ireland lists 39 per cent of the population identifying as Irish, 35 per cent identifying as English, and 26 per cent identifying as Northern Irish.

“That is the first time that has happened,” notes Doherty. “The first time in our long history that so many people here have identified as Northern Irish. It speaks volumes about how we now see ourselves and how far we have come in such a short time. What I believed has happened is that the younger generation has taken the best of both worlds and simply discarded the rest.”

And while those influences remain apparent across the cityscape – the English, Victorian-era architecture and Savile Row style, and the Irish warmth, wisdom, and wit – Doherty is correct in his assessment; Belfast is no longer an ‘English’ city, nor is it an ‘Irish’ city. It is, rather, and international city. And it is an inclusive city.

Respect

Respect

“I arrived in Belfast from Nigeria four years ago,” recounts 24-year-old Ada Yakuba. “I came here to study hospitality and just fell in love with the city. After graduating I took a job at a restaurant, and now I work at a hotel.”

At first – and as a young, gay, black woman with a distinct sense of style that honours her African heritage – Yakuba was concerned that she might not feel at home in her new environs.

“It was the opposite, actually,” she shares. “From my very first class I had other students coming up to me, welcoming me, inviting me out. Within a few days I had a whole new group of friends. Since then, I have become active within the LGBTQI+ community and, just recently, I joined a climate action campaign.”

Like Yakuba, thousands of young people from other countries have arrived in Belfast over the last decade, enticed by a solid education system and a strong economy.

“There are lots of jobs here these days,” notes Yakuba, “especially in the hospitality sector. In fact, staffing shortages have become a real issue for some businesses – we have seen it right here at the hotel. Of course, COVID-19 didn’t help. But we stayed positive, and things seem to be bouncing back now.”

With pandemic lockdowns fading in the rear-view mirror, Yakuba and her friends are enjoying their freedom once again.

“I love the lifestyle here. It is so much fun. On any given night we can eat at a great restaurant, go clubbing, have a few drinks at a pub, see a show…I even went to my first ice hockey game a few weeks ago! It was awesome! And there are excellent shops here – from higher-end clothing stores to bespoke boutiques to funky, out-of-the-way second-hand spots – I love it. It’s funny; my family just came for a week-long visit, and they had to stay at a hotel because I had no room to put them up – I have so many clothes!

“My father was skeptical about me staying here after I graduated,” she continues, “until he met my friends. They are all so sweet and nice, and he sees that I am happy when I am with them. About half of them are from here, and the other half are from Europe, Africa, Australia, and North America.”

Similarly, members of both her LGBTQI+ community and her climate action group are a mix of both locals and those from other parts of the world.

“For whatever reason we have found each other and feel comfortable with one another here. Belfast is a safe place, and it is very multicultural, very inclusive. I belong here.”

Those same sentiments are echoed by many young people in the region today. That inclusivity, that sense of belonging, was certainly aided when Northern Ireland legalized gay marriage two years ago. That youth-driven sense of unity has since been strengthened by peaceful rallies around the city against climate change, racism, COVID-19 mandates, and the recent Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“We – and by me, I mean people my age in Belfast – aren’t interested in local, petty partisan politics. Our concerns are bigger than that, though we do what we can on the ground right here at home. What’s the saying? Think globally, act locally.”

Renaissance

It has been said that spiritual awakenings are most often preceded by rude awakenings, and that – to quote Churchill – those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

“Peace here was hard-won, and it has been prosperous” shares Michael Doherty from the front seat of his cab. “Trust me when I tell you we won’t be giving it up anytime soon, if ever again.”

As we pull over in front of The Garrick Bar on Chichester St in downtown Belfast, I request one final question.

“Go ahead,” he replies.

I pause and take a deep breath before blurting out, “How in God’s name do you people manage to drive on the wrong side of the street with a steering wheel on the wrong side of the car?”

“Ha!” he laughs, turning to me with a smile. “Go on, get out of here you crazy Canuck!”

I pay the fare, close the door, and bid my newfound friend adieu. The pub is buzzing with music as young people of all sorts stand outside, drinks in hand, laughing and smiling.

I look up to the sun. And then, on the side of the building, I see it.

A nation that keeps one eye on the past is wise.

A nation that keeps two eyes on the past is blind.

Stephen Patrick Clare, 2022

For the ones who stayed.

For the ones who left.

And for all the ones who were lost.

Leave a Comment