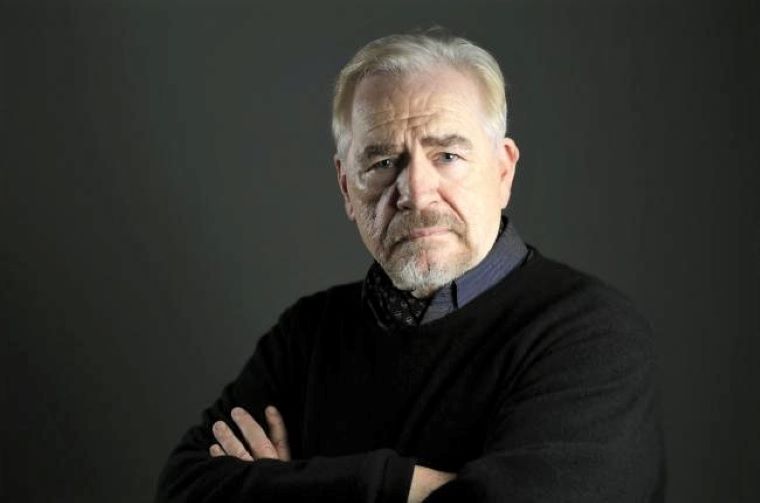

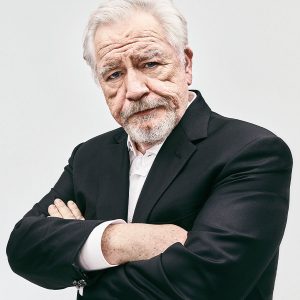

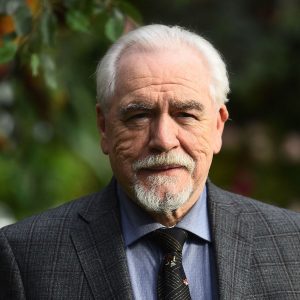

“Ah, the cardigan question,” Brian Cox announces in a Scottish stage whisper. He chews on it.

Having just now pointed out to him that Logan Roy — the dark-lord media mogul he plays in HBO’s hit series Succession — does appear to enjoy his shawl cardigans, he concedes that it does evoke something: a wolf in sheep’s knitwear.

“The avuncular cardigan,” the veteran actor reaffirms, relaying that it all started in the first season of the show, back in 2018, when he decided he wanted to wear something more comfortable in some of the scenes set in the offices of Roy’s empire, Waystar RoyCo. That is when it was born, and has since become a thing.

“They show up here and there in the new season,” he says about season 3, which starts streaming Oct. 17 on Crave, after a long, much-lamented, pandemic-delayed hiatus. But there are decidedly fewer of them, especially in later episodes, because, as he notes, “we had been shooting in Italy.”

“The 37 degrees we experienced in Florence …” he trails off.

Okay, so fewer sweaters, but just as much subterfuge. That is what we can expect to see, once more, from the dysfunctional, motley crew on Succession, a family saga that is deliciously savage and diabolically comic. With Cox in the role of the caustic patriarch, and all his children caught up in a never-ending Rubik’s Cube of approval and aspiration, there is no wonder it has become candy for the zeitgeist and the chattering classes. Its flock of celebrity fans run the gamut from Drake to Jon Bon Jovi to Leonardo DiCaprio to Hillary Clinton. Its operatic theme song, a fixture in memes, has been reinterpreted by rap artists and has no end of YouTube videos devoted to it. Succession is no stranger to Emmy love, winning Outstanding Drama last year, with Cox nabbing a Best Actor nomination.

For a man who has played everyone from King Lear to Titus to LBJ on the stage, not to mention Winston Churchill — as well as the original Dr. Hannibal Lecter on film in Manhunter — is this the role of a lifetime? I had to ask, especially with the thespian on the line via Zoom from his country lair in upstate New York.

“He is not a man without his passions,” Cox says about playing Logan Roy. “He does have pain that is the key to him. He is very disappointed in the human race. Humankind — it is right in the mud, for him. He’s a nihilist.”

The mogul “has suffered at the hands of treachery and deceit, all stuff he is capable of himself.”

Certainly, there has been plenty to mill from in real life. As much as the show has rather obvious allusions to the Australian-American billionaire family helmed by media tycoon Rupert Murdoch, there are can’t-miss nods to a swath of powerful families. There is a clear parallel, for instance, to the infamous Chappaquiddick incident in 1969 involving Senator Ted Kennedy, in the closing moments of season 1.

“They are all in there,” Cox says, listing other billionaire media moguls. “Conrad Black. Sumner Redstone. The Mercers.”

“The Maxwells,” I throw in, referring to the other media dynasty that has made waves recently, because of the ongoing Ghislaine Maxwell saga, and her role as alleged fixer to the late convicted sex trafficker, Jeffrey Epstein.

“They all have their baggage, clearly…. Whereas, the Roys have their own baggage,” Cox says now about the many parallels to those aforementioned families. “But it occasionally overlaps, like when we were on that yacht last season.” (This is a reference to the vessel owned by publishing tycoon Robert Maxwell, Ghislaine’s father, who was lost at sea in mysterious circumstances in 1991.) While nobody goes overboard in the episode — the thrilling second season finale — there is so much jockeying for power and psycho-warfare among Roy and his kids, each person on the ship almost feels like they could.)

And, then, there are the Trumps, of course. For Sarah Snook, who plays Shiv — the prodigal daughter who is trying to establish a rival court to her family, but cannot quit daddy — “That was actually the brief,” she revealed in an interview when the show launched. “Think Ivanka.”

While Cox does not expound on the Conrad Black inspiration, the show’s creator, Jesse Armstrong, has said he studied up on the erstwhile Canadian media baron. Indeed, one clue is that Logan was raised by his aunt and uncle in Quebec before moving to America, as we learned early on in the show.

In its examination of power, entitlement and unfathomable inequality, you might even think of the show as an updated take on the robber barons of the Gilded Age, just with saltier language.

When asked if he has invented a backstory for Logan Roy, since he is still such an elusive character, Cox admits that he has.

“I kind of keep my backstory to myself,” he clarifies, because “that is sort of a shifting feast. It has an organic shape, depending on what Jesse has in mind, what I do … and what he picks up on — what inference I create.”

Long-time gossipist Ben Widdicombe, who is a New Yorker by way of Australia — and has mingled with the Murdochs over the years, as detailed in his 2020 memoir, Gatecrasher — offered this bit of analysis recently on Cox’s feat in Succession. “Brian nicely captures the swashbuckling quality you find in New York billionaires who are also immigrants. There’s a twinkle in the eye of a Rupert Murdoch or a Conrad Black that you don’t get with the American super rich, who are brought up to believe everything is theirs by right anyway.”

Widdicombe, the editor-in-chief of the Upper East Side bible Avenue, says there are many similarities between the Murdoch and Roy family structures. “Which is why it’s such a fun parlour game to speculate, ‘Oh, Shiv [Roy’s only daughter] is supposed to be Elisabeth Murdoch and Marcia [his third wife] is Wendi Deng [Murdoch’s third wife]. But Brian doesn’t seem to play Logan as a character study of Murdoch,” he writes in an email. “The mannerisms and the diction aren’t alike, although he does capture the veneer of charm, which leaves nobody in any doubt that he would kill you and eat you on the spot if there was a dollar in it for him. The pathological, rapacious amorality of the 0.01 per cent is something Succession gets very right: that Sackler-ian bargain of, would you poison the world if it meant holding onto your personal privilege? Of course, they would, every day.”

Something Widdicombe enjoys about the series, in general? How “the audience is craning their necks to take in every sumptuous detail of the furniture, art and real estate that surround the Roys, which they of course never notice themselves, as rich people don’t.”

As a keyhole into the world of the 0.01 per cent, Succession has its own visual language, be it the ubiquitous black cars that loom almost like characters in the show — sleek and shiny as an oil spill, gliding through the streets of Manhattan — or the helicopters they use to get to anywhere, stat, like spiders in the sky. In one hilarious scene set in a red-hot restaurant, in a kind of initiation into the rich, Shiv’s fiancé, Tom (Matthew Macfadyen), introduces bumbling Cousin Greg (Nicholas Braun) to an expensive delicacy made with the endangered ortolan.

“It’s a deep-fried songbird,” Tom begins to educate, “you eat it whole. It’s a rare privilege … and it’s also kinda illegal.”

Undoubtedly, though, it was another dinner scene in Succession that captured the public’s imagination the most — a second-season episode known as “Hunting.” On a hunting trip to Hungary, a conflict erupts over a plan to acquire a rival news organization. A dinner in a lodge leads to a vicious game initiated by Logan, where he forces all the Roy men — including his screw-up son, Kendall (Jeremy Strong) — to play-act like pigs and fight over a piece of sausage.

Cox is circumspect about this iconic moment. “It made me nervous. I just wondered if Logan was going to be overexposed in that episode, because of the rage. I realized you can’t have too many episodes like that.”

Where will the show go, indeed, when it returns? Cox, like HBO, is characteristically tight-lipped, but they do promise an all-out “family civil war” (their words), prompted by the surprise ambush carried out by Kendall against his father at the end of season 2. The stack is loaded against Logan — politically, personally, financially — and watching him squirm might just be half the fun.

If we have learned anything from this show, it is never to count Logan out. The whole series began with Logan incapacitated by a stroke, which started the family infighting and his quest for a Waystar successor. Then, of course, the patriarch bounced back and decided not to retire.

As a portrait of ageism, Logan is less about sowing his oats and more about the idea that the best is yet to come — the best takeover, the best revenge and the best one-upmanship. In other words, it ain’t over until it’s over, and his brand of wisdom is often just reverse-contrarianism. In one subplot, when Logan wants to buy a string of TV stations in Indonesia, his heir apparent, Kendall, is appalled because he thinks his father is out of touch with the digital era. Then Kendall buys a Buzzfeed-type website and, after it implodes, Logan makes him shut it down. In the aforementioned season 1 finale, Logan uses the death of a waiter in a car accident as leverage to make Kendall bow to his will and call off a planned takeover. Father knows best, indeed.

The more I talk to Cox today, the more I become aware of a major tool in his arsenal: his voice. It is a powerful burr that he puts into enviable use on Succession, but has, alas, also been used in ads to sell everything from Scottish independence (his political cri de coeur) to Quarter Pounders (yup, an ad for McDonald’s).

To whom does he owe that voice? He points to a voice coach he had when he was 16, growing up in Dundee, Scotland. She focused “on the diaphragm … how not to get anything trapped in the throat.”

When he moved to England to attend the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, “I still had an accent you could cut with a knife … but then I developed this voice. It was hidden. But it’s in the family. My younger son has the same voice — the same clarity.” (Cox has two university-age sons with his wife, German actress Nicole Ansari, and two older children from a previous marriage.)

This got us to considering the fading art of elocution. “My favourite thing in America is Turner Classic Movies [the cable channel] — I have it on 24/7,” Cox continues. “That is what I love about those old movies — the clarity of the speaking. Nowadays, that clarity is terrible. Interchangeable. When you think of Cagney, you think of Bogart, you think of Cary Grant … They all had a distinct tone to them.”

That flashback to Scotland causes the conversation to veer to those salad days, which will be revealed in detail when Cox’s memoir, Putting the Rabbit in the Hat, comes out Oct. 28 in the U.K. and Canada, and in the U.S. in January 2022. Born and raised in the eastern side of the country, he was the youngest of five, the product of a shopkeeper and a spinner. His father, who had made a lot of money and lost a lot of money, died from cancer when Cox was eight. His mother, who suffered a series of nervous breakdowns and was treated with electric shock therapy, was largely absent from his life. Taken care of primarily by his sisters, it was a Dickensian childhood, by all accounts.

People who have lived in poverty always feel like everything is conditional, he likes to say. To this day, he has a bigger wardrobe than his wife, he told the Guardian last year, because he is a terrible hoarder. After growing up with nothing, he can’t bear to give anything away.

He stumbled through school with no great distinction, but the cinema was his happy place, and he started going to the movies on his own when he was six. Then, in his teens, theatre turned out to be his refuge. It was also “the great leveller,” as he has often said, where class and background are irrelevant.

Ironically, that blast of social mobility gleaned during the ’60s has eroded to some extent in England. With posh-ification in effect — and so many of the most high-profile actors, like Damian Lewis, Eddie Redmayne and Dominic West, coming out of the Eton trough today — he thinks it is emblematic of the working class being excluded from culture, in general. It is something he often talks about.

Which, of course, dovetails nicely with some of the more persistent themes on Succession, where extreme wealth corrupts extremely; where, for instance, we get vignettes like the “summer camp for billionaires” the Roys head to in one episode, a direct parody of the annual Sun Valley conference in Idaho, where moguls rub shoulders and curry favour.

Considering just how much realpolitik and social climbing goes into his day job, it is no surprise, finally, when Cox mentions how he spent most of lockdown in 2020. He was at his place in the country, away from his main home in New York City, with his family, just staring at nature, with occasional runs to nearby Massachusetts to procure his regular supply of marijuana. (It was a habit he took up in his 50s to relax, realizing only then what he had missed out on, being so “square” in his younger days!)

It is a terrible time for the world, “but, in a way, it was like a gift for me,” he says of the first days of the pandemic in March 2020.

“There was still snow on the ground upstate … and I was there watching the snow melt and be ripped away. And get muddy. And then the trees. The buds come out. The leaves come out. And then the animals. The woodpeckers. And the wonderful chipmunks. It gave me a chance to stop,” he said, ending this reverie.

So, basically, it was Logan Roy’s worst nightmare.

Leave a Comment