If Nova Scotia is New Scotland, then perhaps its provincial neighbour to the northeast should be called “New Ireland and Labrador.”

The scenery is so similar, in fact, that BuzzFeed created a quiz challenging readers to spot the differences between photos of the province and places in Ireland. To say it isn’t easy is an understatement.

That likeness goes beyond the landscape, however. The 2015 piece “There’s one place like home in Newfoundland, Canada” from the Irish Examiner reads: “Newfoundland feels like Ireland 20 years ago, when people left their doors unlocked, hitchhiked without fear, and took the time to stop and chat.”

Newfoundland (NL) is said to be the only place outside of Ireland to have earned an Irish name: Talamh an Éisc, roughly translated from Munster Gaelic to mean “Land of the Fish.” Look a little closer and you will find hints of Irish (and other Celtic cultures) in the province’s music, food and dialect.

Newfoundland (NL) is said to be the only place outside of Ireland to have earned an Irish name: Talamh an Éisc, roughly translated from Munster Gaelic to mean “Land of the Fish.” Look a little closer and you will find hints of Irish (and other Celtic cultures) in the province’s music, food and dialect.

One of the reasons for the strong Irish influence in NL is – of course -emigration, which goes back hundreds of years.

“Irish and English experience over three centuries should be taught properly in the high schools,” says John Mannion, author of Irish Settlements in Eastern Canada. A historical geographer by trade, but retired since 2005, Mannion has been “researching the background of the Irish-Newfoundland experience in the field and archives on both sides of the Atlantic” for most of his academic life.

“From their inception, the Irish migrations to Newfoundland emanated from a small region in the homeland. No province in Canada drew its immigrants from so concentrated a space.”

According to Mannion, the highest number of people came from Waterford City and New Ross, along with the town of Carrick-on-Suir.

Seasonal Irish migrations to Newfoundland began in 1675, when young Irish men came to work on contract for English merchants and planters. As young Irish women joined the migration and married the men, those seasonal migrations evolved into permanent family settlements. The pattern increased, writes Mannion, due to the collapse of the old migratory cod fishery after 1790. A greater influx of Irish migrants, particularly women, followed between 1800 and 1835. The population growth “helped transform the social, demographic, and cultural character of Newfoundland.”

In Larry Dohey’s opinion, the Irish in Newfoundlanders “is bred to the bone.” Celtic peoples of Scotland and Wales inhabit NL as well, but they exist in “small pockets.”

Dohey is the director of programming at The Rooms: A museum, gallery and “public cultural space” in the provincial capital city of St. John’s.

“We are immersed,” he says of Irish culture.

“Our traditional Irish music is difficult to distinguish from our Newfoundland music. We continue to use old Irish phrases and words. Our folklore comes from our Irish ancestors.”

That folklore includes stories of hags and fairies, reminiscent of storytelling from Ireland and other parts of Europe. Dale Jarvis is an expert on the on the topic, and holds the only full-time provincially funded folklorist position in the country.

“A lot of European settlement in Newfoundland happened earlier than in many parts of Canada, so the folklore in many ways is quite old. A lot of the Irish settlement in Newfoundland, for example, happened in the 18th century, long before the later waves of Irish emigration to North America,” he explains. “Then, because of the relative isolation of some communities, traditions were maintained for much longer than they were in more urban areas, or even in the home countries where those traditions came from. So some traditions are both older, and better preserved, than they might be in other provinces.”

Over time, these stories and traditions evolved into something unique to Newfoundland. By way of example, Jarvis points to tales of fairies, which he says have been “surprisingly resilient” over the years.

“A common charm against the fairies in many parts of Newfoundland was keeping bread in one’s pockets. This is more of a West Country English tradition, which blended with Irish fairy traditions in Newfoundland over time, and which eventually died out in the parts of England where it originated.”

While Newfoundlanders don’t genuinely believe in fairies to the extent they once did, those tales still thrive. In fact, Jarvis says there seems to be a resurgence in fairylore in the province. He points to the novel Blasted by Kate Story, as well as Robert Chafe’s play Butler’s Marsh, both of which draw on that mythology. In addition, NL’s oral traditions and storytelling have been kept alive through both the St. John’s Storytelling Festival and the St. John’s Storytelling Circle.

“The province produces an amazing number of storytellers, authors, playwrights and comedians, all drawing upon our strong oral traditions,” notes Jarvis.

“Newfoundlanders and Labradorians are very proud of their roots, and I think there is something profoundly Celtic in the way people are tied to the land and sea, their stories, legends and myths.”

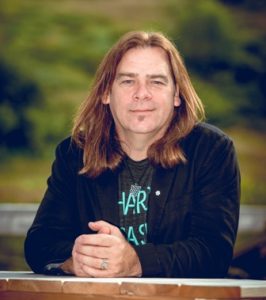

As those customs are so ingrained, a child in Newfoundland might grow up with Celtic traditions and influences without even being aware of their origins. Such was the case for Alan Doyle, former frontman for Great Big Sea who has since embarked on a solo music and writing career.

“Our Irish accent – the southern shore, where I’m from, speaks the way people spoke in Waterford around 1880,” says the renowned songsmith.

As a kid in Petty Harbour, a small town about 15 minutes south of St. John’s, Doyle spent a great deal of time listening to Irish and Newfoundland folk music.

“I was so lucky to grow up in a musical environment. Almost 99 percent of the music I played, I played to facilitate some kind of gathering.”

When he first started making music of his own, it didn’t occur to him that what he was doing was Celtic, Irish-influenced or folk.

“Before I was – say, 13 or 14 – it was just music,” he explains, adding that while his father was listening to John Denver or The Clancy Brothers, he would put on Def Leppard and Bon Jovi.

“I never even thought of those two styles as being radically different.”

Founded in 1993, Great Big Sea recorded and performed to worldwide acclaim for almost two decades. The band was, and still is, famous for its epic sea shanties – the type of tunes that have Celtic roots. GBS has also been referred to as Celtic rock, or “aggressive folk.” Even as Doyle’s career changed course, the Celtic flavour is something he has taken with him, “especially in the instrumentation.”

“My first instinct in building some sort of instrumental hook or theme for a song isn’t electric guitars and pianos and keyboards, the way it probably is for a lot of pop and rock musicians. For me, it’s always accordions and fiddles and mandolins and whistles. Those are the things that come to mind first. Those are the ‘melody’ instruments, which make the songs sound Celtic almost instantly.”

Doyle laughs as he recalls his first visit to the Emerald Isle.

“It was one of the great disappointments of my travelling life when I first went to Ireland and there wasn’t a welcoming committee at the Dublin airport going, ‘You’re home! Welcome back. Thank you for continuing the culture elsewhere. A very short time after, I realized how unreasonable an expectation that was.”

Back then, he believes that “Irish people weren’t as aware of Newfoundland as Newfoundlanders were of Ireland.”

That appears to have changed in recent years, however. For instance, a southeast Irish group goes by the name Newfoundland (or, “Newfoundland the band” to clear up any confusion). The group’s website notes that “The band got their name from the connection between their home region and the Canada’s Newfoundland, where many Irish emigrants settled long ago.” The Irish sextet realized a dream earlier this year when they toured their namesake province.

Newfoundland, Doyle points out, has a very distinct subculture, due, in part, with the islanders’ need to be self-sufficient in their entertainment.

“Newfoundland is one of the last holdouts of a generation of people that were disconnected, isolated and of themselves. So we became unique and real and organic, and looked to our own backyard.”

He recalls the local CBC television program The Wonderful Grand Band – a St. John’s-based variety show starring a musical group and comedy troupe of the same name – from the late 1970s. For Doyle, they were “bigger than The Rolling Stones.”

“There are not many people who can say that when they were 10 years old the biggest thing in their entire pop culture lives was from 20 kilometres away.”

Irish dancer Shawn Silver owes a great deal of his inspiration to a local CBC program as well. Titled All Around the Circle, the show featured Silver’s Portuguese grandfather as a dancer.

“You can imagine, as a little boy who loved dancing and loved that whole element of traditional dance, to see your grandfather there – it just made it all the more real for me,” he recalls.

Silver is the founder of iDance, which he started in St. John’s in 1994. It is the only dance centre focused exclusively on Irish dance in Newfoundland and Labrador. He has been involved with dance most of his life.

“From my earliest memories, dance and music and rhythm were really normal, natural things,” he shares, adding that old-school Kitchen parties were a regular occurrence. “It is kind of a cèilidh, in a sense. For us, it was all about accordions and guitars and banjos and mandolins – and men were traditionally the dancers.”

Still, Silver wanted more. He knew there was something beyond the limited steps he saw at parties “around the bay” or in his grandfather’s kitchen. At age 5 or 6, he saw a dance competition that inspired a desire for more in-depth training.

“That was it for me; there was this whole array of a whole other language that was being spoken and it was a broader, bigger language. I knew that what they were doing was the basis of it all, but I knew there was more. More technique, more stylized, there was a larger history behind it.”

Kristin Harris Walsh agrees. The St. John’s-based dance scholar and writer has done her fair share of research on that history. Initially trained in ballet, Walsh became “hooked” on step dance after moving to St. John’s in 1997 to begin her PhD in folklore. She became so interested in the influence on Irish culture in NL that she wrote her dissertation on the topic by focusing on dance – specifically how traditional dance practices exist in NL today (in particular, step dance and set dance) and why Irish culture continues to be performed through dance in the province.

“There are a number of forms of Irish step dance and Newfoundland step dance,” she explains, singling out three distinct styles of Newfoundland step dance: traditional NL step dance (or the “kitchen party” style of step dance), Irish-Newfoundland step dance (which was brought to NL from Ireland when the Christian Brothers founded schools here) and the ‘Riverdance’ style of step dance, “which is Irish in origin and exploded around the world after Michael Flatley premiered it in 1994.”

Shaun Silver ended up leaving the province to go to school, heading for Montreal at age 16. There, he pursued the formal dance training – including Irish dance – that wasn’t yet accessible in his hometown.

“When I started to learn it, it just made perfect sense to me,” he says of Irish dancing. “I just hadn’t had all the exposure yet, but it was perfectly inside me.”

Returning to Newfoundland was never in question. And when he did come home, he brought his newfound skills back to share with others.

“Every Newfoundlander, we have this longing – a need to be where we are from. We’ve all been out in the world, honed our crafts and skills, before coming back here to offer it and teach it and live it.”

And live it, they do. Especially when it comes attached to Irish roots.

“When we talk about Celtic culture in Canada, it comes back to Nova Scotia and Newfoundland,” continues Silver. “We are kind of the granddaddies of this Celtic bit. The heart of it really is here in the east, isn’t it?”

As for Walsh, she is currently researching the connection between sean-nós step dance in Ireland and traditional Newfoundland step dance.

“While it’s still too early for me to share results, the fieldwork that I have done indicates that there are clear similarities between the two, both in terms of how dancers move and the social contexts in which they danced. And of course the cultural links between Newfoundland and Ireland are important here too.”

One need only visit the island, talk to the locals, and see a show to understand that Newfoundland has an Irish presence. But something remains unclear: Why is the Irish heritage so much more apparent than that of other settlers? As Walsh points out, demographics “show that there are far more individuals of English descent than Irish descent” in NL, adding “I’ve always been fascinated by the extent to which Irish culture is important here.

One need only visit the island, talk to the locals, and see a show to understand that Newfoundland has an Irish presence. But something remains unclear: Why is the Irish heritage so much more apparent than that of other settlers? As Walsh points out, demographics “show that there are far more individuals of English descent than Irish descent” in NL, adding “I’ve always been fascinated by the extent to which Irish culture is important here.

“I think there are many possible reasons as to why Newfoundland has embraced and internalized Irish culture so fully. They are both island cultures who were dominated by the British for many years. They both have strong rural cultures, with communities that would have been isolated from urban cities as well as from each other. There are similarities in religious and folk belief traditions, terrain, and many other small but fascinating cultural traits. The arts here – music in particular, but also writing, dance, etc – drew, and keep drawing, heavily upon those influences.”

Leave a Comment