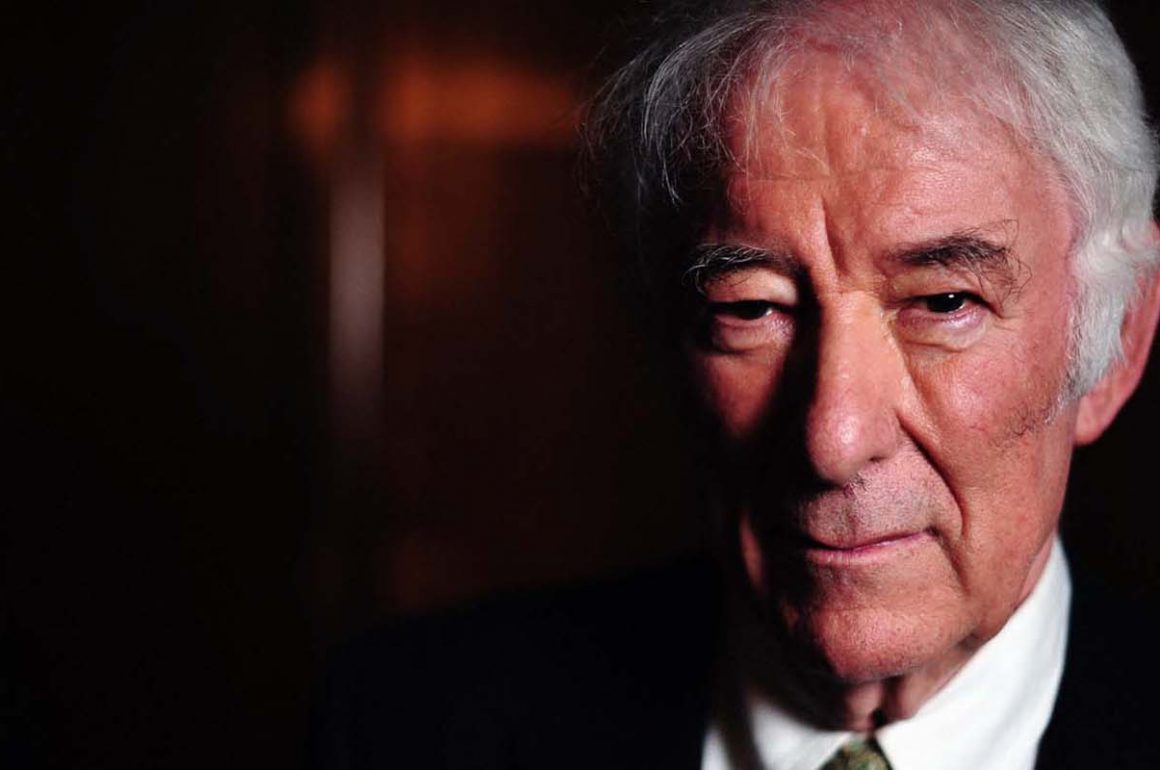

Northern Ireland’s finest scribe and Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney died on August 30, 2013, in Dublin at the age of 74. From our October 2013 edition, Irish journalist and filmmaker Maurice Fitzpatrick remembers the man and his work.

When Seamus Heaney was twelve years old, his younger brother, Christopher, was knocked down by a car while playing on a road near their farmhouse in South County Derry. Heaney was then at boarding school, a hugely intelligent scholarship boy who had entered halls of learning hitherto sealed off to his caste (Northern Ireland was changing). On that morning, Heaney served mass at Nazareth House in front of the school, and after the service, he was brought to the president’s room and told that his brother had been killed. The poem he wrote about his return home for the funeral became so signature a piece in his oeuvre, so widely recognized a poem, that he became reluctant to read it in public, almost as though it no longer belonged to him. It was one of the earliest poems that lifted Heaney to the popular and critical esteem he would have for the rest of life; a poem that marked the sudden pain of death:

He lay in the four foot box as in his cot.

No gaudy scars, the bumper knocked him clear.

A four foot box, a foot for every year.

In later life, Heaney wrote again about the loss of Christopher in the poem Keep Going, which he dedicated to his brother Hugh, who had taken over the farming of the Heaney home-place. The poet would have known how hard it was for Hugh to turn down that road most days of his life, inevitably recalling the tragedy. He would have known because something similar happened to him. When I asked Heaney about the death in a documentary film, he replied that on the drive home from boarding school to bury his brother, “We passed a little field that day in the car. For years and years afterwards when I passed that field I noticed it and it always brought back that moment.”

I first approached Seamus Heaney when I asked him to participate in a film for RTÉ/BBC about the school where he received his secondary education, St. Columb’s College in Derry. I was then living in Tokyo, and when he learned that I was trying to organize the film from there, he was full of sympathy and willing to work around my schedule. That is the Seamus Heaney I remember. No airs or graces, yet full of grace, and in whose poetry we are encouraged to walk on air.

As an honoree of St. Columb’s College, in interview he managed to deal deftly with the more brutal aspects of the Catholic education he received there, recalling, “On the first day in the Big Study…I had never seen such execution, such executive strapping.” Yet his eyes laughed at his own use of the words and at the experience.

Being the eldest sibling of a family of nine, the Head Boy at St. Columb’s College, one of the first from a farming-class Catholic background to enter Queen’s University Belfast as a student and soon after a lecturer, Heaney was set from the first on a course from which he never strayed. He took the lead and led by example: Heaney’s life is a study of exemplary conduct from the thorny avenues of a sectarian society through civilized self-expression and the encouragement of mutual understanding.

He was aware of the ‘representative status’ that being of the first generation to benefit from the 1947 Education Act conferred. His journey from a background of limited opportunities to acceptance in the most renowned arenas, while remaining most comfortable in South Derry and continually celebrating the local in his poetry, has been a recurring feature of tributes to Heaney. He seemed to share Auden’s hope that good poetry could be, “like some valley cheese, local, but prized elsewhere”.

Father Andrew Dolan of St. Mary’s Church, Bellaghy, who officiated at Heaney’s burial mass on September 2, stated that Heaney “wanted to be buried in the same graveyard as Christopher”, the brother he lost so long ago. He is also buried beside his parents, Patrick and Margaret—in our end is our beginning. In a revealing poem from his last collection, Human Chain, it is clear that Heaney, their first-born, was not so much the result of their marriage as its cause, a fact they had to keep quiet in conservative South Derry.

Heaney’s parents had great regard for him, something that enriched his sensibility throughout his life. He recalled his mother going to meet him at the bus station when he returned from school, so that they could have some time together before the young Seamus got swamped in the commotion of the house. He also reflected, years afterwards, that his leaving the home-place to go to school in Derry City was a searing experience for his father:

That summer before college, him in his prime,

Me at the time not thinking how he must

Keep coming with me because I’d soon be leaving.

Heaney inherited a worldliness from his father, a cattle-dealer, whose job it was to know whether men he met at a market were buyers or bluffers. Young Heaney accompanied his father and witnessed these transactions. Unsurprisingly, he came to have a knowing expression, and looked the world in the eye.

Heaney gazed into unknown worlds with equal brio. A man who invested so much of his life plumbing the netherworld—descending to the underground in his Virgil and Dante translations—confided to his long-time editor and friend, Karl Miller, that he hoped to see his father again, like Aeneas setting off into the underworld in search of his father.

Ireland has no equivalent of Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey. Burying our renowned poets in a beautiful church in the capital city could never take root. One’s place of origin, the intimate sense of connection to a place, remains all-important in Irish life. Patrick Kavanagh’s remains belong in Inniskeen and Heaney’s belong in Bellaghy. Accordingly, Seamus Heaney’s final journey was from his family home in Dublin to his ancestral soil in Bellaghy.

In his last known interview, Heaney stated, “I think that I am basically a ground person, you know, if it came to which element…I am sedimentary…That’s an image for consciousness in this country.” Fields, a cut of road, a well, a gap or a riverbank were, in Heaney’s mind and pen, transformed into a part of a greater Being, a living entity. The people and places of his earliest experience were his great subjects. He beautifully illustrated how his people made his place, and place, his people.

Out of this solid base and “hearth language”, Heaney’s work developed in remarkable ways. He learned to incorporate Latin, Greek and Italian poetic traditions and meters; to be cultivated through contact with Polish and American poetry; to comfort the oppressed —“with the farming of a verse/ make a vineyard of the curse,” in Auden’s words. The better side of our nature is nurtured and educated by Heaney’s poetry.

Recipients of his generosity—schools, communities, charities, young writers—mourn his passing. He is a loss to Ireland, but also to the world. A celebrated figure at Oxford, Harvard, the Swedish Academy and the White House, we remember him as a humble and wonderfully vibrant human being.

Now, there is a void. Heaney is survived by his three children and his extraordinary wife, Marie. He has left the Irish population at a loss. We are all bereft, but also filled with gratitude for one who gave us such a high example. His books and his contribution to our country will endure. Heaney acknowledged that poetry does not change anything, but that it can enable a more profound understanding of our world. Through that enhanced understanding, we do better things, we effect little changes and we just might achieve moments of transcendence in work and in life.

And some time make the time to drive out west…

You are neither here nor there,

A hurry through which known and strange things pass

As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways

And find the heart unlatched and blow it open.

Leave a Comment