The last time Celtic Life International checked in with the Highland Village Museum in Cape Breton – a living testament to the island’s unique culture through the centuries – they were gearing up for a big overhaul of their infrastructure, building several new historical facilities, and revamping their busy interpretive centre.

“The new welcome centre is the key piece of the whole thing,” shares Rodney Chaisson, director of the Highland Village Museum. “It is a 7,500 square-foot building that will house our gift shop, reception, two exhibit spaces, a multipurpose base, library archives, and of course, our offices. We have already opened parts of it. It was a $6.8 million project. We started off with a new washroom building on the hill adjacent to the church, to help with cruise ship visitations and church functions. And we have a new period shingle mill. We are looking at having our official opening for the new welcome centre in the spring of 2023, to coincide with Gaelic Nova Scotia month (May), and the 250th anniversary of the landing of the (ship) Hector in Pictou, which was the starting point for all of the Gaelic diaspora in Nova Scotia.”

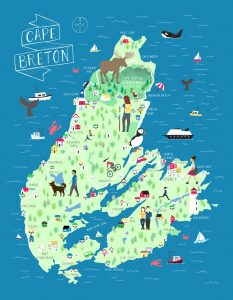

Cape Breton as a culture exudes an essence like no other, with a hospitality that finds its roots in its mixed heritage.

“It is very unique,” shares Chaisson. “Certainly, the Gaelic culture is deeply rooted in Scotland, there is absolutely no question,” adding that much of the Gaelic presence on the island stems from the Highland clearances. But the Scots aren’t the only people who called Cape Breton home, and as such, they don’t hold a monopoly on the island’s identity.

“We enjoy a good relationship with our Mi’kmaq neighbours – the Highland Village in particular is located between three Mi’kmaq communities, Eskasoni, We’koqma’q, and Wagmatcook – and there is a long history of interconnection between the two.”

The Mi’kmaq people have long called Nova Scotia home, long before the Celtic diaspora arrived on its shores. They settled Cape Breton, as well as much of Nova Scotia and parts of New Brunswick, over 13,000 years ago. They were there to welcome the Scots when they arrived looking for greener pastures.

“There is a great story of the founding of Iona,” regales Chaisson. “Donald Òg MacNìll, who was serving with the British forces during the siege of Louisbourg, came through the Bras d’ Or Lake, saw how wonderful it was, and brought back a message to his family in Barra in Scotland. They came over, and there was the start of what could have been a confrontation with the Mi’kmaq people. But a cross was hauled out, and they had a little feast. It was the start of a connection between the Gaels and the Mi’kmaq.”

Others would immigrate to Cape Breton as well, seeking their own fortunes, and the island was soon populated by the Irish, as well as by Ukrainian and Polish settlers at the onset of industrialization.

“Also, the Acadians, the French Acadians,” adds Chaisson. “After the expulsion in Annapolis Valley – the other side of my family tree – they settled in Chéticamp and Isle Madame. We have two very strong, vibrant Acadian communities here.”

“There is a big connection between the Mi’kmaq people and the Acadian people, historically,” says Lisette Aucoin-Bourgeois, executive director of the island’s Acadian historical society, La Société Saint-Pierre. “The Mi’kmaqs sort of took us under their wing when the Acadians first settled here.”

Chaisson connects the cultural dots.

“What we have now is a cultural Mecca, with all these little pieces of ethnicity that form the fabric of Cape Breton today.”

Of course, Cape Breton isn’t the only place on Earth where disparate cultures co-mingle. North America is a tapestry of multiculturalism, with the United States calling itself a ‘melting pot.’ However, Chaisson doesn’t believe that term suits the cultural make-up of Cape Breton.

“‘Melting pot’ means different things to different people. In America, it means you become English. That is not what it is here. It is more of a mosaic. There is a lot of sharing amongst cultures – certainly, you can see influences in parts of Inverness County between Gaels and Acadians in terms of music styles. I mentioned the connection between the Mi’kmaq and Gaels, and that is a big part of it. They are still able to express their own identity, but we kind of do it together.”

That is not to say that there has never been friction between the different cultures of Cape Breton. North America also tells the story of the genocide of indigenous peoples, and Cape Breton is not innocent in that regard. Nova Scotia’s residential school was located in Shubenacadie on the mainland, but there are many people in Cape Breton’s Mi’kmaq communities who are survivors of – or the descendants of – the residential school system, where young native children had their language and culture stripped away from them.

“There have been issues,” Chaisson admits. “It certainly wasn’t always a rosy past, and we are now in the process of doing some work to explore that.”

Those troubles are among the topics that 23-year-old Morgan Toney, from the Mi’kmaq community of Wagmatcook, thinks about – and now, sings about. Throughout his childhood, the sounds of Celtic fiddle music were ever-present in his home.

“It all started when Ma would play recordings,” Toney recalls. “She had these records of all the well-known Cape Breton musicians; Rita MacNeil, Natalie MacMaster, The Barra MacNeils. We would listen to these people on car drives or at home. I remember Ma cleaning the kitchen or the house, and she would have the music blasting. I heard all this stuff growing up.”

As nice as it was, it was all pleasant noise to Toney until a fateful day when he paid a visit to his late Uncle Fabian when he was seven years old.

“He had this DVD playing, and it was Phil Collins. This was the first time I had ever seen anybody perform live on stage. I just loved the look of it. My uncle didn’t say a word because he knew something clicked in my mind. I was in awe, and at the end of the DVD, he told me to take it home with me.”

Music became a fascination throughout his youth – two pots and a frying pan were his first set of drums – and he watched VHS tapes of Mi’kmaq fiddlers – Lee Cremo and the Prosper Family, to name a few – on repeat, copying their mannerisms, which he says helped open up the wider Mi’kmaq culture to him.

“I discovered who I am as a Mi’kmaq person, and I learned a lot about our culture, our spirituality, our psalms, our dances – everything that makes us who we are.”

At 17, he received a fiddle of his own from a friend and started paying closer attention to the master fiddlers of the island, both Celtic and Mi’kmaq alike.

“I discovered a whole bunch of Cape Breton fiddlers. I would listen to these artists – how are they playing, what techniques are they using? What could I do to sound like them?

“I heard that my great grandfather played the fiddle, and three of my late great uncles played the fiddle. My family was pleased that I finally picked up the instrument because it had skipped a generation. I found a passion there. And Cape Breton University has all these connections to Celtic Colours (International Festival) and the Celtic music scene here. This is how I found my idols, and my idols became my friends.”

Today, Toney is known to many as “the Mi’kmaq Elvis,” having made a career of mixing Celtic fiddle music with Mi’kmaq songs and teachings – a style he calls “Mi’kmaltic.”

“Back in 2020, we recorded my song Ko’jua,” recalls Toney, who often collaborates with Cape Breton musicians Keith Mullins, Jesse Cox, and Isabella Samson. “We added the fiddle, we guitar, drums, bass, harmonies – all of these instruments that you hear in today’s music, we brought it to the Mi’kmaq culture, and released it to the world. People didn’t know what they were hearing. But they loved it, because it was so fresh, it was familiar, and it just made sense.”

Ko’jua is far from Toney’s only hit. He has released a full-length album, First Flight, which is filled with his eclectic collection of fast-paced Celtic fiddling and traditional Mi’kmaq sounds. Sung in a mix of English and the Mi’kmaq language, many of his songs explore the more somber aspects of Mi’kmaq life, having written tunes about the missing and murdered indigenous women (The Colour Red), and of course, the impact of the residential school system.

“When they found the bodies of these young children in the residential schools across the country, we composed another song – Aqantuk. What that basically means is, we are on the front lines. We are talking about the survivors who were on the front lines and are still on the front lines today.”

Toney believes that these somewhat taboo topics are made easier to digest through song – especially for non-Mi’kmaq Cape Bretoners, for whom these can be hard truths to swallow.

“Cape Bretoners are open to learning about our history. They are really supportive, from the people that I talk to. They want to know what really went down at the residential schools, and they are ready to hear the truth. We are trying to create hope, peace, and understanding. How can we bring non-indigenous people into our community? How could they better learn about us?”

Aucoin-Bourgeois, who recently invited Toney to perform for her organization in Chéticamp, believes that Cape Breton could use more of what he is offering.

“He is open about the fact that he has been influenced by all the other cultures, and he is a very good ambassador of what we are trying to do here on Cape Breton Island.”

The Acadian people make up a relatively small percentage of the island’s population, so they have had to work harder to retain their cultural identity.

“We are a little pocket of less than 3,000 people,” estimates Aucoin-Bourgeois. “In the province of Nova Scotia, we are less than four per cent Francophone, so we do have to kind of fight to save what we do have left.”

Like Toney and the Mi’kmaq community, the Acadians have also been highly influenced by the sound of the Celtic fiddle.

“We are French Acadians, and we do sing in our native language, but everybody who plays the fiddle here in Chéticamp has been influenced by Celtic culture,” says Aucoin-Bourgeois, noting, however, that while there is a distinct Acadian style of fiddle playing, it is better suited for accompaniment thanas a solo instrument. “It has been very gradual – a process that just happened naturally over generations.”

And, also ike Toney, Aucoin-Bourgeois believes that there is some magic in the sound of the fiddle in its ability to bridge barriers and celebrate both the similarities and the differences in cultures.

“There is no better way to teach than through music. What we realized is that maybe we were all doing our own little things in our silos, and we needed to open that door and talk to each other more,” continues Aucoin-Bourgeois. “Pre-pandemic, we had started a group called MAGIC – the Mi’kmaq, Acadian, and Gaels of Inverness County. The one goal we had was to get to know each other better.”

Aucoin-Bourgeois says the simplicity of the group is that there are no by-laws, nor an internal leadership hierarchy – just members of each community, getting together at events a few times a year, to share their respective customs with each other.

Sometimes, they would gather for a milling frolic with the Gaelic community, and share their own version, la folie. Another time, the Acadians of Chéticamp invited the Gaels and the Mi’kmaq to participate in their mid-lent tradition of Mi-carême – which resembles mummering – sharing molasses cookies with their masked visitors.

“We have a festival each June called Roots to Boots,” explains Aucoin-Bourgeois.; “‘Roots’ because of our shared roots as a community and a culture and, as it takes place in nature, we walk in boots. One year, we had the kids participate at the Cape Breton Highlands National Park, and we had a drumming group from Waycobah. They did the friendship song and the elder song, and then the chief explained about the smudging ceremony. Three cultures, together. That’s it – that is how we should be living our lives. It has been a great little success story, and we need to get this going again.”

Chaisson surmises that the shared language of music is part of the reason why the distinct cultures on the island are able to be so hospitable with one another and with newcomers without losing too much of their individual identities in the process.

“Cape Breton has always been a welcoming place,” he says, adding that the cultural makeup of the island continues to grow, with Cape Breton University drawing in new residents from India, China, and across Asia. “The Mi’kmaq certainly welcomed the Gaels. They welcomed the Acadians. And we have been welcoming people ever since. It is just part of the hospitality nature of the island. Whether you are coming as a visitor, or you are coming to stay, there is a warmth and welcome here.

“Music is surely something the island is very well known for, and I it has been, and continues to be. a great way to connect the cultures,” he continues. “The central part of the island has some fantastic Mi’kmaq fiddlers, which is a Gaelic tradition, but we’ve got some fantastic tradition-bearers that are Mi’kmaq. It is part of how we welcome people.”

“Music is surely something the island is very well known for, and I it has been, and continues to be. a great way to connect the cultures,” he continues. “The central part of the island has some fantastic Mi’kmaq fiddlers, which is a Gaelic tradition, but we’ve got some fantastic tradition-bearers that are Mi’kmaq. It is part of how we welcome people.”

Aucoin-Bourgeois agrees.

“It is the best way to promote our cultures and to talk about the combination and interaction between cultures – through music.”

“In Cape Breton, there are no limits in the music scene,” says Toney. “We should learn about each other’s cultures. We should learn about our history – both the good and the bad. How did our paths cross in the past, and how will they cross in the future? I would love Cape Breton to be the place to go to learn about all our cultures – a place where cultures can work with one another.

“I think we are on our way there. Slowly, but surely.”

Leave a Comment