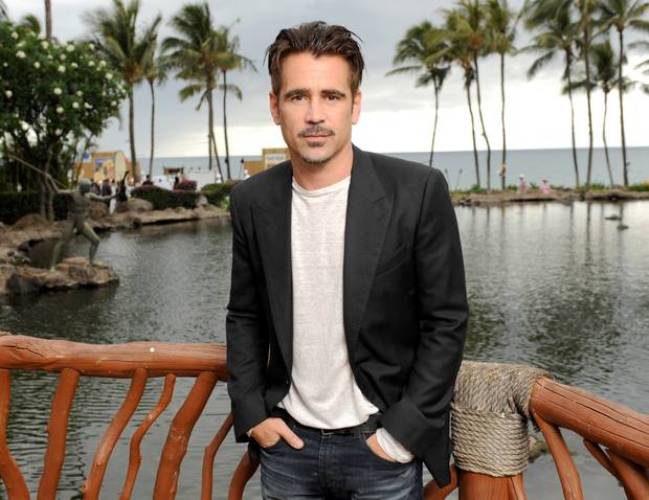

Some movie stars, when their multi-million dollar budget film comes out, have a glass of Chardonnay and enjoy the moment. In 2004, when Oliver Stone’s epic Alexander was released, Colin Farrell received such a critical mauling for his performance in the title role that he got drunk out of his mind and vanished on a plane to Lake Tahoe. More than that, the young Brando from Castleknock – whose illustrious career was unravelling in front of the eyes of the world – hatched a plan, as he told the New York Times last week, to deal with the public humiliation: he not only got blind drunk, but he put on a ski mask so that no one would recognize him. “Where can I wear a ski mask and not actually be put against the wall by a bunch of SWAT cops?” he told Cara Buckley in New York Times of his Lake Tahoe degradation.

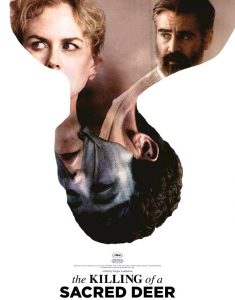

Thirteen years on, Colin Farrell has no need to hide from the critics ever again. Following on from director Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Lobster two years ago, he has just made one of the best films of his life (and of the year) with the spookily compelling The Killing of a Sacred Deer, also by Lanthimos. In it, heart surgeon Steven Murphy (played with a chilling detachment by Colin) finds himself faced with a choice of killing a member of his family after being cursed by 16-year-old Martin (played by Barry Keoghan) whose father died on Colin’s operating table a few years previously.

Instead of filing a malpractice claim, Martin brings horror to the idyllic middle-class home of Steven and his equally detached wife Anna (played by Nicole Kidman) instead. It transpires that Steven had a couple of drinks before he performed the open-heart surgery on the boy’s father that resulted in his death.

Does Colin believe that people are only out for themselves? “I don’t, actually. I believe the majority of the time, yes, but I think there are always exceptions. I don’t think there is one rule over every single person on the planet. I think choice comes into it. I do think that people act from altruism and if somebody acts from altruism and they feel good about it, well, then the more cynical amongst us will go: ‘Ah, they didn’t do it selflessly!'”

Colin’s character kills, or sacrifices, his son. Does Colin see The Killing of a Sacred Deer as a modern take of God asking Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac, in the Bible?

“Yeah. We have always looked for context in mythology, and the Bible to me is one of the great mythological books that has ever been written. I see it as allegory. The idea of sacrifice has always been a huge theme in the human experience, and there is no greater sacrifice than in this case the father taking the life of his child in the belief that there would be some resultant purification. That’s where Martin’s heart very much is. He is a very prideful man. He carries himself as if he is a God. He feels every day that he is cradling the creation of human life, the human heart, so that he can perform surgery. He is like Alec Baldwin in another film [Malice] where he plays a surgeon and says: ‘Do you think I’m God? Let me tell you. I am God!'”

Is Colin religious? “I don’t align myself with any particular religion, or any particular philosophy on it,” Colin says, and he is searching for “even a proximity with regard to what our purpose in life may be. I have a mishmash of this and the other. But I tried very hard years and years ago to be an atheist, because I thought it was more interesting or I thought it had more intellectual validity or worth – and I couldn’t quite cross the bridge,” Colin says of atheism. “I couldn’t quite make it to the other side. I do believe in something that is bigger than us. To someone who is atheist they would say that is a cop out. But I think there are other realms. I think there are greater things than the eye can see or the brain can even comprehend, especially when we are only using 10pc of the brain’s capability. So we can only comprehend what we can comprehend,” Colin adds.

“You know, our evolution as sentient beings? I am completely fine that there are complexities and mysteries that are way beyond the understanding of any human being. Having said that, I don’t find science and religion to be a dividing force. I think they can go hand in hand.

“I don’t know what I am,” he says returning to the original question of religious belief. “I struggle with it.”

In terms of his artistic, rather than spiritual evolution, does Colin feel he has gone through a transformation with indie movies like The Lobster and The Killing of a Sacred Deer?

“No. From the inside of it, it is really not so much [that],” he explains, meaning it is reductive to see his career as action hero box office hell to salvation in indie hipsterdom. (‘Hitting bottom after a string of macho roles in major movies, the actor has found fulfillment, and the best reviews of his life, in oddball films’, wrote one critic.)

“I feel that I am doing work that is more challenging to me as an actor and to me as a man. The work I am doing now is less physical. It is deeper. From the outside looking in. I see the results of the sculpture. But for the sculptor, who is creating the sculpture, it happens bit by bit, step by step. You arrive wherever you arrive as a result of a thousand choices and happenstances. So for me it is like the grandmother not seeing the grandchild for five years. ‘Oh my God! The size of you!’ But if you see the grandchild every day it wouldn’t be hugely dramatic. I don’t see the change that you have asked me about as such,” he says meaning metamorphosis.

Did you need to kill Colin Farrell, the big movie star, the big action movie star, in order that Colin Farrell could live?

He laughs. “I think the box office killed that for me, man! I rose very quickly through the ranks and had a lot of commercial success very early and couldn’t make head nor tail of it. I did a couple of big films that didn’t work. Then there wasn’t the opportunity to do big films and it sort of forced my hand and it took me to involve myself in a scale of work and intimacy of work that I do find fundamentally more interesting. Truly fundamentally,” he says.

“Even through the years when I was doing big films or more commercial films, or action films, I was still doing Intermission [in 2003] or A Home At The End Of The World [2004] and still trying to do smaller films and sometimes it didn’t work that way. I was working with the likes of…Martin McDonagh is an extraordinary director obviously,” he says.

After the multi-million dollar global flop that was Miami Vice in 2006, McDonagh approached Colin to play hitman Ray in In Bruges in 2008. I’d heard that Colin (after the critically beating of Miami Vice and Alexander in 2004) believed his presence in In Bruges would be a negative one and, as such, didn’t want to do it. Is that story accurate

“I always wanted to do In Bruges,” he says. “I was feeling low enough on myself to allow that internal malaise to result in me saying to Martin, [despite] what I thought was an act of generosity [from Martin] and [despite] loving the material: ‘Look, man. People are going to come into the cinema – if they come in, that is; they might stay away! – with a load of baggage from the last few films I’ve done’,” Colin recalled what he said to the In Bruges director. “You have a relationship with your audience as an actor, whether you’re in a theatre or in film or on television.” I ask Colin what was his relationship like with himself at that time. He said in a 2009 interview in GQ magazine looking back on the deeply troubled period after Miami Vice and Alexander: “I didn’t want to die. But I didn’t want to live.”

How did he get his belief back as a human being, not as a movie star? “We all talk about that you can’t live in the past but there is a trap in that as well, especially if, like most of us, no matter what your individual story is, or however beautiful or hard it is. It certainly benefited me to go back. To reverse the clock a little bit. ‘So, OK. Hold on a second. I did that. Hold on a second. Where was I? What was I doing when I was a kid? Why did I do that?’ I kind of went through my whole life just to see where I made some choices and choices were based on fear; and how confused I may have been and I was trying to pretend that I wasn’t confused. All that kind of jazz,” he explains.

All that fear and all you went through is pretty normal, I say to him, except you did it in front of the eyes of the world.

“It is certainly not abnormal what I went through, sadly,” Colin says. “It is pretty much a garden variety tale of an addict, I suppose. And having an addiction and not knowing as a man what to do in a male-dominated society that puts worth and high value on emotions of alpha behaviour and pack mentalities and such.”

And where vulnerability becomes something to laugh at, I say to him.

“And it becomes carcinogenic,” Colin says. “You know, if we as men don’t know how to deal with fears then it becomes carcinogenic. It results in violence and all sorts of madness. So, I had a look back and it was very garden variety stuff and I started dealing with it. That’s all. It was in the past. I was in a bit of a fog. When I met Martin [McDonagh] I was in a bit of fog and I had to understand myself and have a relationship, I suppose, with my own discomfort.”

Why did Colin decide to enter rehab after Miami Vice finished filming in 2006? “I had just had it, man. I was done. For a long time I put the brakes on. For a long time. I could go mad for three, six months, and then I could pull back for a few months to try to re-enter the atmosphere. I couldn’t find the handbrake.”

In 2000, after Joel Schumacher cast him in Tigerland, and then Phone Booth in 2002, the young Irish Brando from Castleknock (who after studying at the Gaiety School of Acting went on to appear in Ballykissangel in 1998 after mercifully missing out on Boyzone) was suddenly one of the biggest box-office draws internationally. The brooding bad-boy of Hollywood was soon, inevitably, bent on self-destruction – he was swimming in a movie-star pool of booze, class A drugs, beautiful women and self-loathing and endless black-outs. He seemed like a young obituary, like Heath Ledger in 2008, waiting to happen. Farrell didn’t believe in self-censorship (he once told Playboy magazine in an interview that “heroin is fine in moderation”) or anything remotely self-nurturing.

Is it true that when he came out of rehab, in the months afterwards, his mother kept expecting to get a phone call saying that her son was dead? “No. I don’t think that was when I came out if rehab. When I came out of rehab that was the best sleep she had in 15 years!”

With neither drugs and alcohol in his life, how does Colin let off steam?

“Run around. Whatever. Go up on hikes. I go into nature a lot, man. I go into nature a lot. I find nature pulls the steam out of you and f***s it over its own shoulder. I go on road trips and go to the cinema and hang out with my kids,” he says. (Colin has his two sons. His first son, James Padraig, was born in 2003 – James’s mother is the model Kim Bordenave – his second son, Henry, with his ex, Alicja Bachleda-Curus, is eight years old.) “I put on a bit of music. I just live. I just live it without being poison the way I was poison for years.” Is it difficult to have that kind of self evolution in a town like Los Angeles where he lives? “No, I think Los Angeles is a good place for it, actually. I am not talking Hollywood. Hollywood is a state of being and also a zip code. But Los Angeles is a very forgiving city. You can be whatever you want. It is actually a good place to reinvent yourself. Los Angeles is an incredible place and there are incredible support groups. There are alternative ways of looking at things. There are people from all over the world. So there is not one particular behaviour that’s followed.”

Be that as it may, is the industry that Farrell works in not difficult sometimes because Hollywood is more likely to push someone towards self-oblivion, rather than nurturing themselves? “Everything in life, every industry is hard, especially with the potential for the amount of money that is on the table. And if people think they can make a dime from you they will lavish you with great praise and gifts – and if the moment comes where they don’t, they will f*** you out the door without a second’s thought and without any concern for you. That is very, very prevalent.”

Colin said a few years ago that he realized that he had entered an industry where money was the priority and that you would get a phone call on Saturday night to tell you what the box office opening was on Friday night and that it was all “horseshit”.

“Yeah,” he says, now, “but I am sure I wouldn’t have been saying that if the phone call I got on Saturday night was saying that the film was number one! I have to call myself out on that! Look, in every aspect of life, no matter what you do, whether you are coaching a football club or you are the head of a Fortune 500 company or what people might refer to as a movie star – whatever you may be – you just have to try and figure out what the true value of living is; and to have a fulfilling and decent life. I am not saying I’m there, by the way.”

How close is he? You sound closer than some of us, I say to him. “Not at all,” he says, dismissively. “Cancel this whole interview if it leads you to think that! I am all over the shop!”

But he is less all over the shop than he was, presumably?

“Ah, yeah. That is for sure. That’s all you can do. If you move in the right direction, however slow you move, once it is the right direction that is a good thing.” Did sobriety make him a better dad? “Oh God, yeah. I can’t imagine! I have yet to meet a person whose sobriety has made their life worse. I have yet to. But I am open to it.

“If you find some one please get in touch with me because I would love to have a chat with them and ask them a couple of questions. I have yet to meet a person whose sobriety didn’t make a better father, a better friend…” And a better actor?

“No idea. I am truly not pulling your leg. I have no idea.”

His beloved big brother Eamon’s husband Steven Mannion was recently diagnosed with skin cancer.

“Steven has been through the wringer,” Colin says, concerned. “About six weeks ago Steven got some tests done on a mole on his back. It had started to bleed and like a lot of Irish lads, myself included, he said, ‘Ah, it’s grand, it’s nothing’. Then he went in and they did a biopsy and he was told that he had stage one cancer melanoma. Then they did more tests and they found out that it had gone to his lymph nodes. He is only 33 or 34. He had his surgery yesterday and they removed his lymph nodes. He is in great shape but he is in a lot of discomfort. I think they got it early enough. There is a bit of work ahead for Steve.”

And a bit of work ahead for the not-so-young-Brando of Castleknock – like the rest of us on the planet – too perhaps out in La La Land. There are worse curses.

Source: Barry Egan / Independent.ie

Leave a Comment