Taking a cursory glance at pop culture today, it is hard to believe that once, and not too long ago, comics were considered childish and for nerds and dorks only. Now, everything has a touch of comics in it.

Marvel (and to a lesser extent, DC) are making major money with movies based on their classic superhero characters. Animated flicks about the Spider-Verse and Krypto the Super Dog are entertaining families across the globe. Some of the best, award-winning television shows are based on characters that originated in the funny pages. Spider-Man even made it onto Broadway!

Since many of the more famous comic characters draw inspiration from folklore around the world, some of those cultures have received a boost in recognition over the last half-century also. How well would we all know the Norse pantheon if it weren’t for The Mighty Thor? And while a fictional nation, Black Panther’s Wakanda has done a lot to elevate the station of African culture in the global consciousness.

So, what about Celtic culture? Has it been pushed by the power of pulp?

There have certainly been Celtic influences in the world of comics, along with characters inspired by Celtic folklore. Perhaps most famous is the mutant Banshee, aka Sean Cassidy, from the X-Men comic series – so named for his superhuman scream that allows him to attack enemies and even fly.

Neil Gaiman’s seminal Sandman series drew inspiration from many of the world’s myths and legends, including the Faerie folk – in the book, the bard himself, William Shakespeare, is shown to have been commissioned to write A Midsummer Night’s Dream for the Faerie king and queen, Auberon and Titania.

There are other examples, but it gets more niche as we go. Why, then, haven’t the Celtic myths and legends taken hold in comics like other folklore has?

When Irish comic creator Nick Roche was young, sneaking away in the basement of The Book Centre in his hometown of Wexford to read the latest issue of The Dark Knight Returns, the comics he was exposed to didn’t feature many Irish icons, and that didn’t exactly surprise him.

“I had a strange relationship growing up with my Irishness,” Roche explains, chatting with Celtic Life International over Zoom from his home office in Waterford, where he now resides. “I guess I never thought it was ‘cool.’ You didn’t see it represented that often, outside of Ireland. And the kind of media that Irish TV station and such were producing was all a little bit cringey.

“There was never anything really that contemporary for us as teenagers. I never paid too much attention to the folklore. It always felt like the Norse or Egyptian mythology had, like, a bigger budget. It looked a bit more epic.”

Even the mainstream superheroes were less plentiful in Ireland in the 1980s, with Marvel having its own U.K. distribution, and with unique titles in that system. Those comics, Roche recalls, were more often based on television tie-in titles, like Knight Rider, the A-Team, and Transformers.

“Because the things I was into were TV shows where the cars are almost characters, those were the comics I leaned into.”

Fittingly, Roche got his big break in comics when IDW Publishing tapped him to write and draw some of their Transformers titles, with Last Stand of the Wreckers becoming a smash hit. Before that, however – self-publishing comic zines in the 1990s – he did dabble in creating an Irish superhero.

“In 1995, I did my own comic called Captain Ireland, which had nothing to do with Ireland, apart from the name. At the time it came out there was an influx of American tourists, and I knew that they would buy anything with the word ‘Ireland’ on it.”

That was when Roche started to notice Irishness getting “cool,” so to speak; U2 was the biggest band in the world, and Irish boy bands plagued the countryside. Over time he began to appreciate what Ireland had to offer pop culture.

“As an adult I realized that I enjoyed the stories. In Ireland, what could be fantastical or part of the mythology – i.e.: what makes it spooky – is because it seems like the everyday life. It is not giant thunder gods or things like that. Scarenthood was born from that thinking.”

Scarenthood is one of Roche’s latest periodical productions. Together with Irish colourist Chris O’Halloran, the comic series tells the story of four parents who try to solve the mystery of the ghostly happenings percolating under their kids’ preschool.

The idea came about when his own daughter entered preschool for the first time.

“I found myself having to mix with other humans – which, for a comic artist, is rather unusual. Through talking to these parents, and going through the mundane, parental minutiae, I thought, ‘this isn’t what being a grownup should be about. Wouldn’t it be cool if we were doing something else?’ There are woods nearby – let’s go hunt some ghosts!”

Roche’s Scarenthood depicts a modern Ireland – where LGBTQ folks and people of colour are just as Irish as any bloke named Flynn or Diarmuid, and one in which classic folklore and contemporary society bleed into one another.

Roche’s Scarenthood depicts a modern Ireland – where LGBTQ folks and people of colour are just as Irish as any bloke named Flynn or Diarmuid, and one in which classic folklore and contemporary society bleed into one another.

“It has been nice to marry the traditional stuff in the comic with the ‘new’ Ireland.”

Meanwhile, in Goose Cove, Nova Scotia, Angus MacLeod is bringing something even rarer to comics; Scots-Gaelic.

Actually, he has been doing it for a while – the world only just now noticed.

“The artwork, that is something that I have been doing ever since I was a child,” says MacLeod, a Gaelic teacher, who has been writing and drawing his own Celtic folklore-inspired comics in Gaelic for years as an evening hobby. “I basically lived in the comic book world when I was a kid. I really didn’t have any goal of having it published. The idea was always in the back of my mind, that at some time, at some point, maybe that would happen. But it was never a motivational factor for doing it.”

That time, that point, came recently, courtesy of Dr. Emily McEwan, president of Bradan Press, which publishes books about Gaelic culture, often in the Gaelic language. McEwan learned of MacLeod’s treasure trove during a sales trip to Cape Breton.

“While we are sitting there, having tea, he pulls out this stack of manila folders, and each one had these pages sticking out of the side,” McEwan tells Celtic Life International. “He had been working on them for years and years. I guess I was the last person to realize that. Even my husband was like, ‘oh yeah, I’ve seen some of Angus’ stories.’ How did I miss this?”

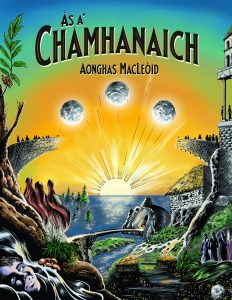

Just like that, Bradan Press was in the graphic novel business, publishing a handful of MacLeod’s stories as an anthology, under the title Ás a’ Chamhanaich.

Some of those stories include a woman’s fight against a creature that can change from a man to a horse called a Glaistig, a crippled fisherman lost at sea contending with creatures of the deep, and the life tale of an elderly woman who was once the town beauty, as told by a former admirer who believes her aging is a story of finding serenity, rather than one of failure.

MacLeod already has enough strips on hand for a second volume, and he is currently working on a third.

McEwan has also added a second comic – Wild Rose, by Halifax author Nicola R. White – to her catalogue by crafting the official Gaelic translation. She believes that comics in Gaelic can be used like comics in other languages have been used in the past – as a tool to help young people learn the language.

“It benefits those working to renew the Celtic languages. When readers have that visual element there are more hooks to hang it on, as opposed to just words on a page.”

While publishing comics can be a challenge for smaller publishers like Bradan Press – it took the help of a few grants to bring the Gaelic translation of Wild Rose, aka Ròs Fiadhaich, to bookshelves – McEwan is eager to publish more going forward.

While publishing comics can be a challenge for smaller publishers like Bradan Press – it took the help of a few grants to bring the Gaelic translation of Wild Rose, aka Ròs Fiadhaich, to bookshelves – McEwan is eager to publish more going forward.

“If there are artists who are interested in telling these kinds of stories, we would definitely like to hear from more people. There are so many different aspects of stories that could be told through this medium.”

Roche, who has more stories planned for his Scarenthood gang, recently saw copies of the title in The Book Centre, and describes the pride he felt seeing something he made with a very Irish identity sold in his hometown comic shop.

“It is the place that was responsible for me doing what I do. And getting to see my own book in my hometown – one that is about Ireland and modern parents and modern concerns – is a great feeling.”

Roche notes that today, in the digital age, being a Celtic comic creator and making titles with more Celtic identities is possible in a way that they weren’t when he was growing up.

“The Irish are really well-represented in the wider comics industry in America because so many are now working for Marvel and DC. There are Irish comic companies, yes, but none of them are big powerhouses yet. However, things like crowdfunding make the Irish comics industry, and comics about Ireland, even more possible and plausible.

“It feels like the industry here is in a healthy place. There have been comics professionals working in Ireland over the last 10 or 15 years. And, as more Irish comics come out in the coming years, the opportunities to promote and preserve our culture will grow.”

Leave a Comment