The story of the 1916 Easter Rising is writ large in Irish history. But what is often overlooked is the contribution made by Irish communities in England and Scotland in providing many of the insurgents, arms and explosives and then taking part in the actual fighting.

They came from across Irish communities in England and Scotland. More than 70 men and at least 10 women are known to have traveled over from the shores of Britain to participate in the Easter Rising. Some eyewitnesses claim that there were as many as 100 men. Others would probably have traveled to Ireland had their mobilization orders not been delayed. Six of the men were killed in action — one of the highest casualty rates of any of the units involved. Many of these participants had been born in England and Scotland — some had never even been to Ireland before. In the words of the Soldiers Song: They had come from a land beyond the sea to man the gap of danger.

Organizing for the Rising

The Easter Rising was masterminded by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). About a fifth of its 2,000 members belonged to its circles in England — particularly in Liverpool and London and in West Scotland — giving them three seats on the IRB Supreme Council. The secretive IRB — some of whose members were too old for combat — had an open military wing in the form of the Irish Volunteer companies in London, Liverpool and Glasgow with about 100 in each city. In the midst of the British war effort these Volunteers drilled and trained for the coming Rising. Some of the London Volunteers practiced their marksmanship in a Leicester Square shooting range while the Liverpool Volunteers installed their own rifle range in a basement.

Arming the Rising

Arming the Rising

The IRB’s long history of secret activities was particularly suited to obtaining and smuggling vital arms to Ireland. IRB members were influential in ensuring that the 1,500 old German rifles purchased in Belgium by London Home Rule supporters organized by Alice Stopford Green, Mary Spring Rice and Erskine Childers were successfully landed by yachts in Howth and Kilcoole just before World War I broke out in 1914. Smaller amounts of more modern rifles and pistols were subsequently obtained in Britain through raids and purchases from soldiers and smuggled to Ireland — often by the women members of Cumann na mBan and the boy scouts of Fianna na Eireann. The Scottish IRB and Volunteers were a particularly important source of explosives. Over 500lbs of explosives and several hundred detonators were stolen in at least three raids on Scottish coal mine magazines in 1915 and early 1916. One consignment of explosives was smuggled by a counterfeit wedding party complete with Cumann na mBan confetti throwing.

Awaiting the Rising In Dublin

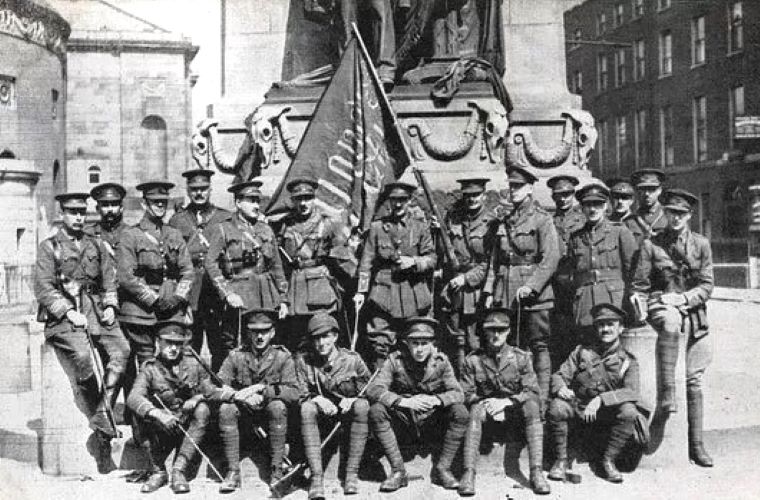

In late 1915 the young and unmarried members of the IRB and Volunteers were advised to leave Britain to avoid their pending military conscription. Even in Dublin they were not safe from the conscription threat as Jimmy Reilly from London was arrested and forcibly conscripted. Men from Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester and London who were unable to find employment in Dublin were billeted in the Kimmage estate at Larkfield. Eventually numbering over 50 — although some accounts say as many as 80 — this Kimmage Garrison spent the several months awaiting the Rising by manufacturing cartridges, grenades and pikes. Michael Collins dubbed them the refugees but Padraig Pearse — who lectured them on street fighting — called them: “The first standing army in Ireland since the days of Patrick Sarsfield.” He also accorded them the honour of being the HQ Company of the Volunteer Staff Command. Another 20 or so volunteers from England and Scotland who had found employment in Dublin were billeted at 28 North Frederick Street.

The Aftermath

It required the combined efforts of Thomas Clarke, Sean MacDermott and Michael Collins to persuade many of the very reluctant English and Scottish volunteers to surrender as they thought they would be executed or sent to fight in France. In the event only John McGallogly was court martialled — for having captured a British Army officer. His death sentence was commuted to 10 years penal servitude as he was only 17 years old. His older brother James also fought in the Rising. The other surviving English and Scottish men were shipped in the dung-covered pens of cattle boats to prisons in Britain. Most ended up in the Frognoch Internment Camp. Many give false names and hence were not properly recognized in later histories. But the London-born Sean and Ernie Nunan, Thomas O’Donoghue and the Liverpool-born King brothers Patrick, George and John were identified, forcibly conscripted into the British Army and harshly imprisoned for disobeying orders. All the prisoners and internees were released by late 1917.

Fighting in Dublin

Fighting in Dublin

Even before the Rising commenced the Kimmage Garrison suffered its first casualty when London Volunteer Dan Sheehan was drowned trying to capture a Kerry radio station. On Easter Monday morning the Kimmage men armed mostly with shotguns and carrying picks and crowbars for barricade construction travelled into central Dublin by tram. Joined by their North Frederick Street compatriots the English and Scottish Volunteers were mostly deployed in the area around the GPO. Because of the delayed mobilization of many of the Dublin Volunteers these English and Scottish Volunteers formed as much as half of the initial force in this key area. Their unfamiliarity with Dublin resulted in London-born Joseph Good and Scottish-born John McGallogly separately getting lost because they didn’t know where the GPO was when they ordered to withdraw to it from their outlying posts. The London accents of Wiliam Daly and John O’Connor also almost got them shot by Dublin men hearing their voices as they went up the stairs to erect roof aerials on the Abbey Street wireless school. Their fellow London volunteer Patrick O’Donoghue used this wireless to tap out the Morse code that announced the birth of the Republic to the outside world. Dublin civilians sheltering in their houses were also surprised by the English and Scottish accents as the volunteers bored their way through buildings when movement on the streets became too dangerous. In the course of the Easter week fighting the English and Scottish volunteers suffered five fatalities — the Glaswegian-born Charles Corrigan, Michael Mulvihill, Patrick Shortis, Sean Hurley and Jimmy Kingston. There may have been other insurgent fatalities from England as eye-witnesses reported the death of a Citizen Army member with a cockney accent called Neale. And Joseph Good recalled the death in action of a London member of the International World Workers Organization.

Women in the Rising

Margaret Skinnider — a Glasgow-born Cumann na mBan member who had been very active in smuggling explosives — attached herself to the Irish Citizens Army garrison in the College of Surgeons as they, unlike the Volunteers, allowed women to engage in actual combat. Dressed in a green uniform with knee britches her training in a Ladies Empire Defense Rifle Club made her a very effective sniper. She was wounded three times while leading a sortie to burn buildings in Harcourt Street. At least 10 other English and Scottish women — a high proportion of the estimated total of 60 Cumann na mBan members involved — participated in the Rising but they were confined to more traditional nursing, cooking and dispatch and delivery roles. Although these were dangerous enough activities in burning buildings and on bullet-swept streets.

Leave a Comment