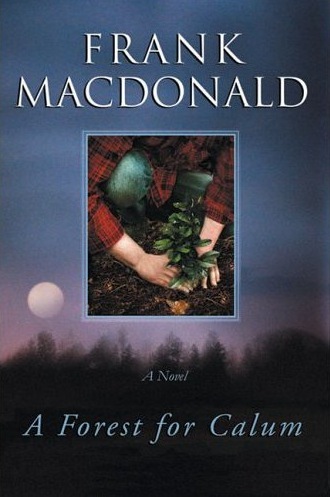

Frank MacDonald

Cape Breton writer, storyteller and playwright Frank MacDonald is the author of A Forest for Calum and A Possible Madness, two novels that were long-listed for the prestigious International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. His third novel, Tinker and Blue comes out this fall. Also an award winning journalist, MacDonald was a long time reporter and columnist for the Inverness Oran; a collection of his famous newspaper pieces were published in the anthologies Assuming I’m Right and How to Cook Your Cat. Recently, we spoke with with MacDonald just after he got back from Scotland, where he had been a guest at this year’s Ullapool Book Festival in May. During an entertaining telephone conversation, he talked about growing up in Cape Breton, the Island’s Gaelic culture and how storytelling has and continues to be a way of life there.

Cape Breton writer, storyteller and playwright Frank MacDonald is the author of A Forest for Calum and A Possible Madness, two novels that were long-listed for the prestigious International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. His third novel, Tinker and Blue comes out this fall. Also an award winning journalist, MacDonald was a long time reporter and columnist for the Inverness Oran; a collection of his famous newspaper pieces were published in the anthologies Assuming I’m Right and How to Cook Your Cat. Recently, we spoke with with MacDonald just after he got back from Scotland, where he had been a guest at this year’s Ullapool Book Festival in May. During an entertaining telephone conversation, he talked about growing up in Cape Breton, the Island’s Gaelic culture and how storytelling has and continues to be a way of life there.

What are your own roots?

My own roots are Highland Scot down through the generations. A couple weeks ago I paid a visit to North Uist, which is where my great-great-great grandfather came from to come to Cape Breton.

So you travelled to North Uist after the Ullapool Book Festival?

Yes. My wife and I took 10 days to go around parts of Scotland and North Uist was sort of the destination because that was where I know one branch of my family originated from. That was my first time in Scotland and the Ullapool Book Festival made it possible.

Did you enjoy your time in Scotland?

Oh tremendously yes! I loved every minute and every place. Everywhere we went from Ullapool to Inverness to Skye to North Uist to Glencoe…any one of those places, we would have been happy to just stop for a week or two—to stay in one area. But we were fast-forwarding our way through. I felt a lot for the country. But I’m not sorry some of my family left because I really feel a lot for Cape Breton too. [laughs]

In North Uist, did you get to go to the very places where your ancestors may have lived?

Yes. There are three separate sources of where they came from in North Uist, but the island is relatively small. You can circumvent the island in an hour, so we were able to visit all the places that had been mentioned. It was more emotional than I expected it would be. As far as I can tell from my own family, in roughly 200 years—depending on which date you believe—I think I’m the first to return there. Now I might have distant cousins branching off, but I know in a straight line down through my grandfather you know, that I was the first in the family to go back there. So I didn’t feel like a tourist. It was more of a sense of returning for other peoples’ sake, none of whom are alive. And it’s an island that has become so depopulated that it’s very easy to find solitude there. So I was more involved in it than I knew going. It was nice.

What was it like growing up in Cape Breton?

I grew up in Inverness, a town in Inverness County. Inverness had been a coal-mining town that died just around the time I was born. So I didn’t grow up in a rural kind of landscape like people from Mabou or Margaree. The town was never that big itself but it was distinct because of its coal-mining heritage. I loved growing up here. Something about the town, something that was given to me at birth or some time, made me aware that this was my home. I knew that this is where I wanted to live. I had been away when I started working for 10 years or more. But I just knew that I needed to come back here. I didn’t know how I was getting back, in terms of making a living, but that worked out.

Tell us about the stories you heard growing up?

Cape Breton was basically a migrant workforce. People were basically leaving for wherever the boom was in North America. So you grew up expecting to go away. But it wasn’t some gloomy future you were looking at. It was something really exciting because the stories that I grew up hearing, and later telling, weren’t the traditional stories about the area—like the great stories about the characters or whatever. But it would be people a few years older than me who had left and gone to Toronto or to Boston or to Sudbury or wherever there was work. They would come back in the summer with these fabulous stories about things that happened on the road. We’d be gathered around listening to these really romantic stories—if you can imagine really romantic stories about Sudbury [laughs]—and just anticipating the time when it would be our turn. When I did leave I found that it wasn’t quite as romantic or as much fun. Being hungry wasn’t good; finding a job and getting up in the morning and going to work wasn’t much fun [laughs]. But things would happen to you and you had all winter to work on your stories. By the time I came home I sounded just like the other liars who came home ahead of me talking about how wonderful this was or what we did there. Never mind that these stories would be rooted in the truth, but they may take in five of the nights you were away all winter [laughs]. You begin learning to tell stories and self-edit and try to make them as interesting as you can. Before hearing from the people just a little older than me who had gone away to work and come back, our house and most houses would be full of stories of parents who had done the same thing through the 1930s Depression, the War…Everybody told stories about when they were away or about people they knew when they were away.

Is storytelling still a part of Cape Breton culture today?

I had the misfortune last night of having to go to a Wake of a friend. A lot of people had come a long way because of this person’s death and good part of the Wake was people trading stories with each other about that person. We’re a culture that’s exposed to the digital realities as anywhere else, but there’s still a strong element of the Gaelic culture in Western Cape Breton that counts on face-to-face stories and not Facebook stories. Storytelling is still a huge part of what we do when we can. There are still are among us, many, many fine and really superb storytellers around here. Occasionally someone will hold a formal storytelling session where people come and talk about history or tell ghost stories and they have stories about the past. I can’t do that in that type of setting. I’ve been asked to speak to a Gaelic gathering tomorrow and for my speech, I need to take a script with me and read it. But come to my living room and we can trade stories all night. But if you put me on a stage and I don’t have a book in my hand, I’m in trouble. But I still consider myself a storyteller—I think I fit that definition more than I fit writer.

What it’s like—storytelling among friends?

If I’m at a house party or a gathering of friends and we’re just playing cards, it’s a bartering culture…a story for you and somebody else has a story and so you’re trading stories like comic books [laughs]. It’s not that blatant, but if you’re counting stories around the table, 10 stories might be told and one or two come from each person. It’s a sort of an exchange or bartering. Then of course, I might find myself in a situation a week or two later, where I’m in a different group and probably telling five of the stories I stole from the previous table. It’s hard to get a copyright on oral stories [laughs]. But when it comes to writing, like with novels, even then I hope I come across as a storyteller. I try very hard to convey the elements of the story through the characters telling their own stories. I use humour quite a bit I think in my writing. I like to create characters, who are not cartoons hopefully, but who reflect the kind of storytelling that goes on and that I’ve heard growing up or used. And most of the stories that we tell have a humorous element. There are lots of tragic stories, but that’s for a different venue.

Do you remember when you first started writing your stories down?

“I was writing poems first I think. But I wasn’t the kind of person that would bring poems out, standing in the street or saying to the guys, ‘You wouldn’t believe the poem I wrote last night.’ They would have said, ‘Ho Ho ho ha ha ha!’ No, no, no, I wasn’t going to go there. When I was working in Calgary, my father became sick in ’76 and I came home to take care of him. I became involved with the Inverness Oran, the weekly newspaper here. My first role there, before I actually became a reporter, was opinion pieces, which turned into a weekly column. My column had no particular routine. It ranged from political satire to an inept bachelor bumbling around in his trailer, like the one that I still live in…Having to meet a deadline was very scary initially, but I think it really helped me learn to write. Then there were other stories I wanted to tell besides the news-based and the factual, and to somehow tap into the storytelling that seems to be part of the culture here. It took a long time before I found a publisher who was interested in what I was writing.

Tell us about your third novel, Tinker and Blue, coming out in September.

That’s a very, very different story, but my main character is, if nothing else, a storyteller. It’s an over the top, kind of hopeful satire on the 1960s. It is very different from the first two novels, so we’ll see how it resonates with readers. I loved writing it. I hope people enjoy reading it!

How has the state of Cape Breton’s Gaelic culture changed over your lifetime?

The first book I wrote, Forest for Calum, is set in the early to mid 60s, and the narrator lives with his Gaelic-speaking grandfather who has never spoken Gaelic to him. That was also the period of time when I was growing up. Until the late 50s to mid 60s, western Cape Breton was still a very isolated area culturally. So a lot of the traditional Gaelic was spoken, a lot of the songs, a lot of the stories…But then an explosion, first with radio, then television, and then the Beatles and then…You know the world began opening up or moving in. So people of my age—teenagers—were absolutely taken with what was going on in the world with other teenagers. If there was a rock band coming to town—and we had some fabulous rock bands even in the town—you’re not going to a square dance. So we were becoming drawn and attracted by what the rest of the world was doing. A change took place in the area, but not a change that erased everything from the past. Even if we were going to a rock concert, we’d come home with stories. If you’re in your home and your uncle and aunt dropped in, the stories they told were still the stories of home. So there was a generation that was moving away from the past, but the past wasn’t going anywhere. Probably one of the most important things to have happened with the culture in Cape Breton, right across the Island, but in Inverness County where I could see it best because we were covering it with the paper, was when the Rankins made an impact on popular music in Canada, followed by Natalie and Ashley. Suddenly the culture that we had turned our backs on was influencing music right across the country and these people were touring all over the world, from Carnegie Hall to Massey Hall to Australia, England, Scotland…The wonderful spill-out from that was the 10 to 20-year-olds in the 90s suddenly embraced what we had sort of let go. There was another insurgence of interest in the Gaelic arts. People began travelling here from all over the world to learn to play music. Still the Gaelic storytellers were in a real struggle to keep the language alive. But the arts can’t exist independent of the language that gave birth to them. There was a hardcore dedicated group of people who were starving themselves trying to foster, salvage and teach the Gaelic language. When Rodney MacDonald created the Office of Gaelic Affairs and brought in some funding, with the political will, this group that had been struggling to keep Gaelic alive became re-energized. The amount of work in trying to get the Gaelic language back into a living form has been amazing. It’s really gratifying and the changes are also ongoing. I’m in my fourth year of Grade 1 Gaelic [laughs] and I’m not quitting either! There’s quite a diverse level of people learning Gaelic and now there are families whose children are being raised in the Gaelic language. All of this feeds back into those 200-year-old roots that the stories come from. As a reporter in the early 80s if someone had told me that there would be hundreds and hundreds of people in Cape Breton studying and speaking Gaelic now, I would have thought it was really far-fetched—somebody reading cards and tea leaves. But the cards and the tea leaves turn out to be true.

-Story by Michelle Brunet

Hello, I have a question for Frank. In the book a A Forest for Calum, you mention “A nickname’s a fact of life around here. Only way to tell John MacDonald from John MacDonald….” and you refer to them as Black Jack and Red Jack in the book. Could you please confirm if “Red Jack” is Rankin MacDonald’s brother?

On a side note, I’ve read your first 3 books, which I actually purchased from the Oran directly and they have been signed, and I’m a 1/3 of the way through “The Smeltdog Man”. I love your books, I love your town, and I’m looking forward to reading more and visiting again sooner than later. Thank you Frank