Language is a funny thing. We all acquire language as children, usually without thinking much about it. Speaking seems as natural as breathing or thinking. And yet language carries with it culture, history, and identity in ways that are so subtle and complex that it occupies the entire careers of trained experts.

Scottish Gaelic – the language of the founders of Scotland and the native language of the Scottish Highlands – has endured almost a thousand years of persecution and neglect. And yet it survives, even if just by a thread. Some very positive developments to benefit the language and its speakers have emerged just in the last few years.

The DuoLingo language learning app started offering Scottish Gaelic in the Autumn of 2019 and has already drawn over 500,000 people to it, surpassing anyone’s wildest expectations. While not all those users are going to become fluent speakers, it has given new opportunities to people to learn about Scottish Gaelic who might not have had the chance otherwise – and to have fun doing so in the process.

Anglophones learning Gaelic will encounter many words that seem familiar, so it is not surprising that one of the most common questions to arise is: What words in English originally came from Gaelic? Answering this question accurately is more complicated than it might seem. For one, both Gaelic and English are ultimately descended from an ancestral language called “Proto-Indo-European,” that existed sometime between 4500 BC and 2500 BC, and there are still words bearing the marks of this common origin. On top of that, both Gaelic and English borrowed words from Latin, French and Norse in the Middle Ages. And then there are words whose similarity is due to pure coincidence.

The study of Celtic languages has long been neglected and under-supported.

However, those efforts too have received boosts lately that aid in understanding how they have evolved over time and interacted with other languages, including the various forms of English of neighbouring communities, such as Lowland Scots. The results provide unique windows into the histories of these societies.

However, those efforts too have received boosts lately that aid in understanding how they have evolved over time and interacted with other languages, including the various forms of English of neighbouring communities, such as Lowland Scots. The results provide unique windows into the histories of these societies.

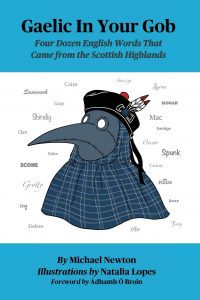

I have just finished a book called Gaelic In Your Gob which identifies 48 common words in “mainstream English” that were borrowed from Scottish Gaelic, often via Lowland Scots but sometimes directly into the English of England and, in a few cases, within a North American setting. I have written a short essay about each word, outlining the evidence for the appearance of the word in English and how it came to be borrowed, along with fascinating and amusing tidbits that illuminate the lives and minds of people in the past. I will offer a couple of simple examples.

I will start with the word “gob” itself that appears in the title of the book. This is a slang term referring to the mouth, usually with mocking, sarcastic, or humorous overtones. It has been used in modern British idioms such as “gob-smacked” (to be astonished), “gobstopper” (hard candy) and “gobshite” (a loud-mouthed or indiscreet person).

Although it is commonly assumed that “gob” is a late borrowing from Irish, it has actually been in use in Lowland Scots since at least the sixteenth century. The word entered northern English dialects by the late seventeenth century and the street-slang of London by the mid-nineteenth century. The Lowland Scots word was borrowed from the Scottish Gaelic gob, which refers primarily to the beak of a bird. This progression from Scottish Gaelic to Lowland Scots and then to other varieties of English is a common pattern in the histories of many words that originated in Gaelic.

The word gob is used for both bird beaks and the human mouth in Gaelic, with overtones of mockery or sarcasm. A common Gaelic admonition used by adults to silence a child is Dùin do ghob! “Shut your beak!”

Gob is used metaphorically in Gaelic for things that resemble beaks and mouths. Gob-dubhain is the end of a fishing hook and gob-claidheimh is the point of a sword. Gob is also used of the end-point of landscape features and can be found in such Scottish place names as Gob na h-Éist (Nest Point) on the Isle of Skye and Gob na Cananaich (Chanonry Point) on the Black Isle between Fortrose and Rosemarkie.

Gob appears in Gaelic adages that comment on human failings and flaws. All talk and no action? In Gaelic, that’s Gob mór, ugh beag “Big mouth, little egg.”

Another Gaelic borrowing worth examining is “cairn,” especially the cairn has become a common form of memorializing Highland emigrants and their legacy in many parts of the world.

A “cairn” is a pile of stones, sometimes arranged neatly to form a stable structure or sometimes to create the impression of a megalithic ruin. Cairns are generally understood to commemorate the ancestral dead in one way or another. The Gaelic term carn was borrowed into Lowland Scots by the sixteenth century – or was at least familiar to Scots speakers. As you might expect, the word “cairn” also appears in the works of Robert Burns and Walter Scott as well around the turn of the nineteenth century.

One of the most iconic cairns in the Highlands was built in 1881 in the shape of a tower twenty feet high at Culloden, commemorating the battle fought there in April of 1746. A replica of this cairn was built in Knoydart, Nova Scotia, in 1938, near the graves of three soldiers who had fought at the Battle of Culloden and emigrated later to Canada.

The original Gaelic word, carn, is used in hundreds of place names across Scotland. The most mammoth instance is the Cairngorms mountain range in the eastern Highlands – although this name was not actually created by Gaelic speakers or natives of the region. It seems to have been invented by Colonel Thomas Thornton, an Englishman who toured the area and published memoirs of his tour in 1804. The native name for the mountain range in Am Monadh Ruadh (The Red Mountain). Although monadh is a commonplace word in modern Scottish Gaelic, it was a medieval borrowing from Pictish.

The earliest surviving explanation of the significance of the carn is from an Old Gaelic tale composed in the eighth or ninth century called Togail bruidne Dá Derga “The destruction of Dá Derga’s hostel.” The narrator of the story digresses for a moment to describe these monuments:

“For two causes they built their cairns: first, since this was a custom in marauding; and, secondly, that they might find out their losses at the Hostel. Every one that would come safe from it would take his stone from the cairn: thus, the stones of those that were slain would be left, and by that they would know their losses.”

In other words, before a battle, every warrior would place a stone in the heap. If they returned from the battle alive, they would remove a stone from the pile. The body count thus corresponded to the number of stones left in the cairn; a tall cairn signifies a tremendous loss of life.

The cairn offers a metaphor for the linguistic debris embedded in English after centuries of conflict with the Gaelic world. There is evidence galore about the history of Gaelic and English, and the communities that spoke these tongues, to be found in the rubble, even if it takes a great deal of time and care to sift through it. Although it would be misguided to overestimate Gaelic’s influence on English or even feel the need to validate the status of Gaelic through that influence, there is still an interesting and important story to tell through the history of these words. Gaelic In Your Gob is my effort to tell that tale, in a fun and engaging way. – Story by Dr Michael Newton https://hiddenglen.org

Leave a Comment