The Highland Clearances is still a very emotive subject to many people, in many parts of the world, today. It consistently provokes people to take sides and has led to deep, and sometimes acrimonious academic debate.

Some historians try to give the topic an objectivity, by associating it with a process of economic and agricultural change which was widespread across Europe at the time. It is undoubtedly a part of the Agricultural and Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and early 19th century. And yet it is much more than that.

Other writers are corruscating in their condemnation of the process – seeing it as an early version of ‘ethnic cleansing’. The Clearances undoubtedly stemmed in part from the attempt by the British establishment to destroy, once and for all, the archaic, militaristic Clan System, which had facilitated the Jacobite risings of the early part of the 18th century. This approach, however, also over-simplifies the issues involved.

People at the time, and since, have seen the Clearances as an act of greed and betrayal on the part of the ruling class in the Highlands: an attempt to hold on to their land and preserve their wealth and status by sacrificing their people. Undoubtedly this motive was present in some instances, with weak people taking advantage of even weaker ones under the guise of economic reform or social reorganization.

The weather has also been blamed – a succession of bad harvests and famine demanding a drastic solution. Rising population, putting pressure on land and jobs, also played a part, as did the persuasive, smooth-talking agents of ship-owners who ferried indentured servants to the rapidly expanding United States of America.

Indeed, in some cases, the final decision to go was a voluntary one – a desire to seek something better across the Atlantic or Pacific Ocean. All of these factors played a part in causing the Highland Clearances, and the results have had a lasting significance for the people of the Highlands, and indeed for many of those who left.

The vanished world

Reconstruction of the township of Raitts at the Highland Folk Museum, Newtonmore, based on archaeological and documentary evidence. In the first place, the Highland Clearances transformed the cultural landscape of the Highlands of Scotland, probably forever. In the space of less than half a century, the Highlands became one of the most sparsely populated areas in Europe. And, it should be remembered, the Highlands and Islands comprise an area bigger than some industrialized ‘first world’ nations such as Belgium or Holland. But it was not only the people who disappeared. The settlement pattern, the homes of the people for a thousand years or more, has virtually vanished, becoming no more than an archaeological feature for those who stumble across the remnants.

Most countries in Europe can display examples of traditional peasant housing going back to the Middle Ages. This is true of England and, to some extent, southern Scotland. But when one comes to the Highlands there are very few buildings of this sort that date from before the early 19th century.

The only way a 21st-century Highlander can experience something of how his or her ancestors lived 300 years ago, is to visit the archaeological reconstruction of a Highland township (or baile) at the Highland Folk Museum in Newtonmore.

Before the Clearances, most Highland families lived in such townships, in a kind of collective, or joint-tenancy farm, housing perhaps a hundred or so people, who were often kinsfolk. The buildings were substantial, but used materials alien to us in the western world today. The walls were of clay and wattle, or of thickly cut turf, with or without a leavening of rough stones, and the roofs were thatched in heather, broom, bracken, straw or rushes.

Once they were cleared, these structures quickly reverted to nature. And little or nothing was to replace them in the new economic order. In one glen near where I live, I can find traces of six or seven such townships, housing perhaps 500 or more people. View the landscape today, and you will see a couple of stone-built houses for the shepherds. They too are now abandoned, and the glen stands empty.

Highland wilderness

Even the sheep, which replaced the people, have gone – to a large extent. The great sheep farms were designed to provide landowners with an economic miracle, providing meat for the great burgeoning cities of the south and wool to the factories, but they became unsustainable by the last quarter of the 19th century, undercut by cheaper, often better quality products from Australia and New Zealand. (And is it not ironic that these lands were so heavily settled by the very people cleared from the Highland glens?)

The land was then given over to sporting estates to become grouse moors and deer forests, the playgrounds of the new industrial aristocracy. In recent years, this use too has declined and large tracts of the Highlands are now designated National Nature Reserves, Sites of Special Scientific Interest, and, perhaps soon, National Parks. However, what is often viewed as one of Europe’s last great natural wilderness areas, is also one of Europe’s great human wastelands.

But not all of the people cleared from the townships were cleared from the Highlands. Many were resettled in new locations, on marginal land and on holdings too small to be viable economic farms. These crofting townships are still a significant part of the cultural landscape today, but they were never meant to provide people with a living.

In the economic theory of the day, powered by thinkers like Adam Smith, the remnant of the Highland population would learn to diversify. They would become weavers, kelp workers (burning seaweed used to make iodine), commercial fishermen, and so on.

The croft would give them a measure of subsistence, while they transformed their lives.

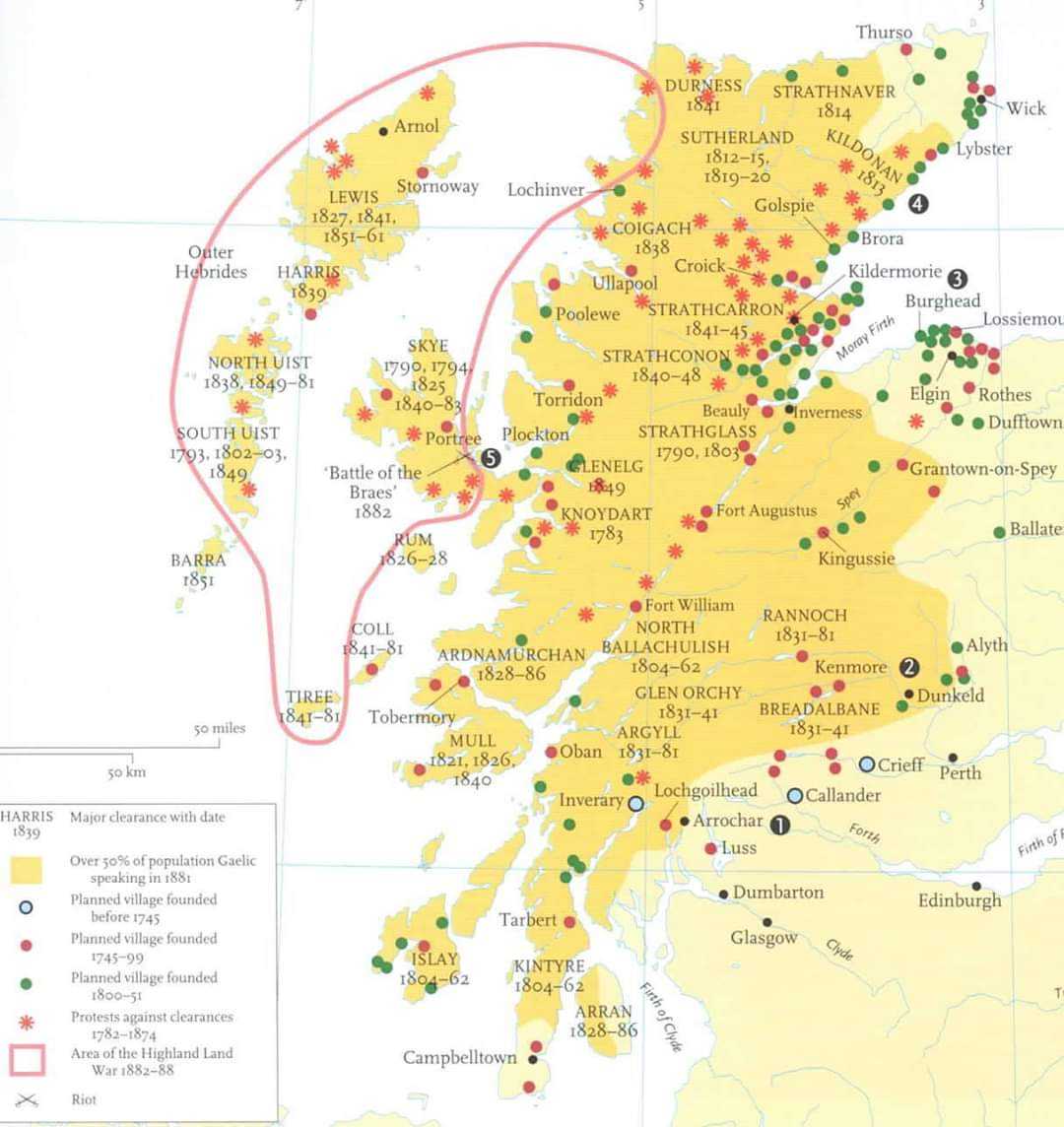

So new settlements grew up, like Bettyhill (named after Elizabeth, Countess of Sutherland, in whose name some of the most infamous clearances where people were literally burned out of their townships were carried out), Helmsdale, Spinningdale and a host of others, which were the forerunner of new industrial estates.

The state too had a hand in this early attempt at resettlement and economic regeneration. The British Fisheries Board established a number of fishing stations, designed to create a new industrial base in the Highlands. Ullapool in Wester Ross, Tobermory on the Island of Mull, and Pultneytown (now part of Wick) in Caithness. are lasting monuments to state intervention in the plight of a society in cultural shock.

Cultural decline

The cultural changes in the landscape are easy to spot if you know where to look and what to look for. It is perhaps more difficult to identify today with the tremendous change in the political culture. Politics in the early 21st century seems to comprise events, issues and policies which are immediate and often short term. For many highlanders who experienced the Clearances, or the aftermath, the change was long-lasting, profound, and, one can argue, far-reaching.

The people of the townships were conservative with a small ‘c’. They lived a lifestyle which would have been recognisable in the 12th or 15th or 18th century. Even those involved in the tumultuous events of the Jacobite risings were, to a large extent, fighting to preserve a traditional version of national political power.

The rank and file took part because being called to fight in the service of their clan chief was a traditional part of the system by which they held their land. Respect for the way of life involved dying for it when necessary.

By the time the worst of the Clearances were over and the remnants of that rank and file were settled precariously in the crofting townships – with no guarantee of security of tenure and subject to economic pressures totally beyond their control – that situation was altered forever.

Respect for the traditional chiefs was fast disappearing, even where they had remained on their lands. But many had as little real benefit from the Clearances as their tenants did, and were forced to sell off land, including crofting land, to the nouveau riche of the industrialized south.

There were few certainties in the lives of these early crofters. Many of the economic initiatives, in which they had been expected to take part, failed, often because of the vast distances between remote crofting communities and their potential markets in the south. Others, like the kelp industry, were short-lived – overtaken and superseded by new industrial processes. The sporting estates offered, at best, only seasonal employment.

Even the language of these Highlanders was under threat, as the state education system vigorously and often cruelly promoted English in preference to their native Gaelic. The one certainty to which crofters clung was their affinity with the land.

They desired above all to feel that they would never again suffer the indignity of being removed from the land of their forefathers. This was no longer conservatism with a small ‘c’, but radicalism with a capital ‘R’.

Highland radicalism

The middle decades of the 19th century saw the Highlands of Scotland at the centre of a national debate on land reform. A radical wing of the Liberal Party, then one of the ‘big two’ in Westminster politics, took the lead most of the time, and radical liberalism reigned supreme in the Highlands.

Many crofters associated themselves with this party and their church, The Free Church of Scotland, which had rejected any form of patronage from the landed classes – and they could easily have been nicknamed the ‘radical Liberal Party at prayer’.

But there were many whose desire for reform took them beyond constitutional reform into the realm of direct action. The Highland Land League, closely linked to its Irish counterpart, was involved in actions of land reform agitation which saw police from Glasgow and even the British Army brought in to subdue land raids and other militant actions by the Highlanders.

This level of radicalism had a profound effect on national politics, splitting the Liberal Party and providing early leaders of the Independent Labour Party.

The action was justified by the setting up of the Napier Commission, which heard evidence from people who had either been cleared themselves or, more usually, from people who were their descendants.

The outcome was the enactment of two Crofting Acts, giving the people of the Highlands a measure of protection in their tenure of land probably greater than they had ever had in the days of the townships. But the struggle had been a long and bitter one, which left scars on the psyche of Highlanders for generations to come.

Moreover, the new legislation did little to make the crofts more viable, or to solve the problem of there being very few alternative sources of employment. Neither did it end the steady drain of population from the area, as many of the young and ablest of its people left the land to seek a better standard of living in the south or across the oceans.

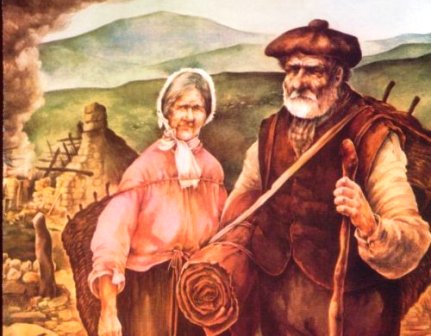

It is most difficult to capture easily the psychological impact of the Clearances on the culture of the Highlands. And yet, in many ways, this was the most profound result. The first clearance of townships for sheep occurred as early as the 1770s, and people were still being evicted in the 1870s. For a hundred years, then, this threat hung over the crofting population, and remained an ever-present reality in their lives. These people were truly the ‘Dispossessed’.

Highland diaspora

For those who went away, the scars perhaps healed more quickly, but they left in their place an incredible sense of nostalgia and empathy with their former homeland. At first this was tinged with bitterness and regret, over what those who left might have become if they had not been forced out.

Certainly, however, by the beginning of the 20th century, this feeling been largely transformed into an emotion of high romanticism. The Scotland of townships lived on in people’s memories as a real place, which one day they, or their children, or their children’s children would visit.

There are far more expatriate Scots – often with only a quarter, an eighth, or even less Scots blood in their veins – than native Scots in the plethora of modern Clan Associations. It is ironic that they give respect to, or even venerate, the chiefly families who were responsible for their departure in the first place.

In some places, Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia for example, they have kept alive customs and traditions that have disappeared from the culture of the homeland. In other places, they have created entirely new traditions – the ‘kirking of the tartan’ in the United States is one example – which help them to legitimise their Scottishness in a new world.

Tartan Week in America, Caledonian Societies across the globe, the international phenomenon of Burns Suppers – these are all really cultural legacies of the Highland Clearances.

For those who were left behind, the psychological trauma created a deep culture of dependency. This was not a fawning, ingratiating affair, for we have seen the deep-rooted radicalism that was present. Rather, it engendered demand upon demand that the state do something for them, rather than a drive to do something for themselves.

Government development agency followed upon government development agency, and crofters in time became more and more adept at working the system rather than trying to change it. Another century passed before a turning point was reached.

In recent years a strong Crofters’ Union has emerged, inspiring crofters to seize the advantages of new transport systems, new communications networks and new technology, to build a better way of life for themselves. In the last decade crofters involved in community buy-out schemes have not only taken full possession of their own lands, but of whole landed estates like Assynt, or whole Islands like Eigg. Perhaps at last the gloomy memories, the shadow of the Clearances, are passing.

Leave a Comment