I am standing side of stage at the Boston Garden arena — I’ve just watched U2’s Experience + Innocence show, a performance that covers the folly of the former and the optimistic power of the latter. It is both personal and political. The final number finds Bono alone on stage with a single lightbulb, staring at a replica of the house he grew up in on Cedarwood Road in Dublin. A Bono doll’s house.

He comes off stage breathy and dripping with sweat. Black jacket, black jeans, black boots and a towel. We swoop into a waiting black SUV. Other SUVs are lined up behind us ready to go. A police escort will flank us as we speed through the city at night into the bowels of a hotel. But this moment is not just about rock-star secrecy and protocol. It’s about seeing Bono, totally spent, soul bared. He talks in jumbled phrases about how he’s on the circumference of awkwardness, about the reconstruction of the American dream, not making sense. He’s undone by this show.

I hold his hand. His is a weak but intense grasp. Apparently, a lot of people loathe Bono. I can tell you that nobody has loathed Bono more than Bono has loathed himself. He can see the contradiction of his situation, raging conscience straddling galloping success.

Usually it’s his wife, Ali, who collects him from the stage and puts him in the car. Once it was Oprah. Today it’s me, so if you don’t like Bono, stop reading this now. We are friends. I’ve known him for 20 years, since we first met over poached eggs at the Savoy several albums ago. I’ve seen him operate first hand at the White House during the Bush regime. I’ve seen him shrink stadiums with his big charisma and soaring voice. I’ve seen him at home as a daddy, as a husband. But I’ve never seen him shake after a show.

I don’t take this hand-holding as a display of affection, it’s more that he physically needs a hand to ground him. His eyes look sad and careworn behind his lilac-tinted glasses. He has a stubbly face, which gives him definition but also vulnerability, as if his face is smudged.

Now we’re in the basement car park of the Ritz-Carlton hotel. He is escorted to a lift that will take him to his floor, where he will stay in his room. I take another lift to the lobby, where there’s a nice bar and where various people who work for U2 are starting to congregate.

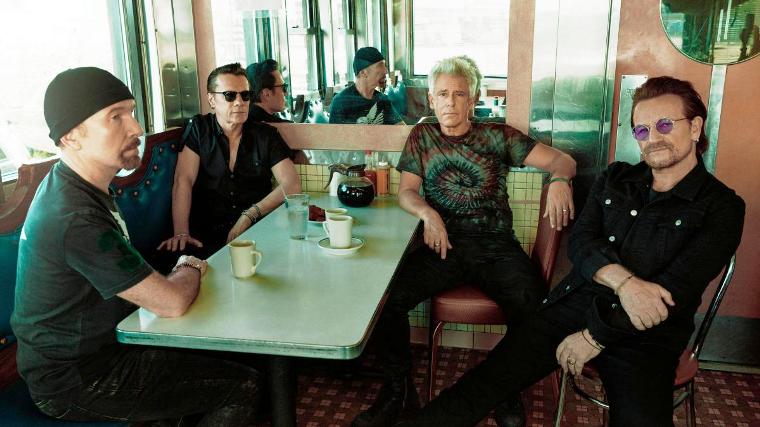

The Edge will come down with his wife, Morleigh Steinberg, who is a creative consultant for the show, but no other band members emerge. They’re all in their fifties. They’ve been on the road for two years and they need to preserve their energy for the next night’s show.

Adam Clayton, the bass guitarist, gave up alcohol in the 1990s, around the same time he gave up supermodels. The drummer, Larry Mullen, has never been a party animal. He’s much too reserved and now needs an hour of physio after the show.

The next day I’m in Bono’s penthouse suite. Room service has delivered a lunch of chicken and greens. He takes the metal covers from our lunch and clashes them together like cymbals. It reminds me of the noise at the start of the show that mimics the deafening sound of an MRI scanner. The accompanying song is about facing death. “It’s not a very sexy subject, mortality, is it?” says Bono, 58. “But what is sexy is being in a rock’n’roll band and saying, ‘Here’s our new song, it’s about death.’

“Does it sound pretentious to say that we are an opera disguised as a rock’n’roll band?” he wonders. Yes, it does. “When opera first started out it was punk rock. Opera only became pretentious. Mozart had a punk-rock attitude.” Let’s maybe not say it’s opera. Let’s just say there are grand themes in the show. “Right,” he says.

Although this show seems to be about Bono’s life, it’s actually about the experiences of all the band members. He may be the lightning rod, but he speaks for all four of them. There was a section in last night’s performance when Bono said he had once lost his head along with Adam, whose reckless years are well documented. “And then it happened to the Edge and Larry later,” he continued. The Edge, a zen Presbyterian, looked askance. When did the Edge fall off the edge? “OK, I was just saying it because I was feeling a little mischievous. I don’t like seeing them looking smug.”

He’s laughing, but he is also serious. “Who would want to stay the same is what I’m talking about. If success means that you trade in real relationships and real emotions for hyper media-centric ones, then maybe success is not good. Early on in the 1980s, I remember being very self-conscious and thinking what newspaper I chose to buy was going to define me. And I remember hanging out with Chrissie Hynde, who was so totally herself at all times. It took me a few years to get there.”

He doesn’t think he was really himself for decades. “In public, I had different selves and all of mine were pretty annoying. We went to watch Killing Bono [the 2011 film, based on a memoir by a former schoolmate], and I said to the Edge about the actor playing me, ‘What’s that accent he’s speaking in? That’s not my accent.’ And the Edge said, ‘It’s the accent you used to give interviews in.’ It’s like people have a telephone voice, and I had one in the 1980s.”

The summer sun streams in and we’re submerged in the hot breath of the humidifiers. Bono doesn’t touch his lunch. In a recent interview, Quincy Jones said that, when he goes to Ireland, Bono always insists that he stays in his castle because it’s so racist there. Which castle is this?

“I love Quincy,” he begins. “But I don’t have a castle.”

He does have a Victorian folly at the end of his garden, though, which Quincy may have stayed in. Most guests do. When I stayed, there was a wall signed by Bill and Hillary Clinton: “A + B = a bed for C.”

“Now that I think about it, [Quincy] did tell me that he had some racist incidents in Ireland in the 1960s, and I said it’s not like that now. Come and stay with us.”

Quincy also said that U2 will never make a good album again because there was too much pressure. “Yes, and Paul McCartney couldn’t play bass. We’re all having these meltdowns, apparently. Most people accept that the album we’ve just made, Songs of Experience, is right up there with our best work. It certainly had the best reviews.”

The tour comes to the UK next month, after shows in Europe. There’s a section with a film showing the neo-Nazi riots in Charlottesville in 2017. How does he think that will work in Berlin, for instance?

“We will rethink it, but there’s plenty of Nazis right now in Europe. I think we can reimagine it with the same spine.” In fact, they decide to start the European shows with Charlie Chaplin’s speech from The Great Dictator: “Dictators free themselves, but they enslave the people! Now let us fight to fulfil that promise! Let us fight to free the world.”

Bono and the presidents

The band have always been close to the American dream and those who dreamt it. Only the other week, Bono went to visit George W Bush.

“I did. And I saw the 44th president last week — I’m still close with Obama.” Barack hasn’t stayed in his “castle”, “but he and his missus and his kids have been in our local pub. I don’t like to think of my relationships with these people as retail. Having gone through some stuff together, we stay together even when they’re out of office.

I saw George Bush on his ranch. He spent $22m on antiretroviral drugs and I had to thank him for that.”

He also recently met Mike Pence, the US vice-president, because of his involvement in the President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief, founded in 2003 under the Bush administration. Was he helpful?

“Well, we haven’t had the vicious cuts that the administration proposed.”

And what about Trump? “I’m wise enough to know that any sentence with his name in will become a headline, so I just don’t use his name. It’s nothing personal. It’s just you have to feel you can trust a person you’re going to get into that level of work with. Lots of my lefty friends doubted I could work with George Bush, but he came through, as did Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.”

Is Trump onside? “No, he’s trying to cut all that stuff at the moment, which is why I don’t want to be near him. If he’d put down the axe, maybe we could work with his administration. But we can’t with the sword of Damocles hanging.”

And Ivanka? “I have no doubt she has the intention to try to move the gender-equality debate.”

Bono worked closely with Harvey Weinstein on the 2013 Mandela movie Long Walk to Freedom, winning a Golden Globe for the accompanying song Ordinary Love. “He did very good work for U2. My daughters are very unforgiving in this regard. Whenever I get philosophical, they tell me, ‘It’s not your time to speak on this.’”

I can’t tell if it’s sadness I see in his eyes or just tiredness. On the liner notes to Songs of Experience, Bono revealed that in the winter of 2016 he’d had “a brush with mortality”. “I was on the receiving end of a shock to the system,” he wrote. “A shock that left me clinging on to my own life. It was an arresting experience. I won’t dwell in it or on it. I don’t want to name it.”

Last year he went further in an interview, describing it as “an extinction event” that was “physical” in nature. So what happened? “I don’t want to speak about it,” he tells me. “But I did have a major moment in my recent life where I nearly ceased to be. I’m totally through it, stronger than ever.”

He’s talking as though he had a decision in the outcome? “No, I didn’t. It wasn’t a decision. It was pretty serious. I’m all right now, but I very nearly wasn’t.”

It helps make sense of many of the songs on the past two albums — some are letters to his children and wife, reflections, conversations with his younger self about how things could have been.

“Funnily enough, I was already down the road of writing about mortality. It’s always been in the background.”

How could it not be? He was 14 when his mother, Iris, died. She suffered an aneurysm at her father’s funeral and died four days later. He has always liked to point out how many rock gods lost their mothers early — John Lennon, for instance. Initially, he and Larry bonded over the death of their mothers. It was always in the background. “And then it was in the foreground.”

Did he have a premonition that this brush with death was going to happen? “No, but I’ve had a lot of warnings. A fair few punches over the last years.”

Like falling off a bike in late 2014 and breaking his arm in six places and his eye socket? He needed a five-hour operation after that one. “That was only one of them. There were some serious whispers in the ear that maybe I should have taken notice of. The Edge says I look at my body as an inconvenience, and I do. I really love being alive and I’m quite good at being alive, meaning I like to get the best out of any day. It was the first time I put my shoulder to the door and it didn’t open. I feel God whispered to me, ‘Next time, try knocking at the door, or just try the handle. Don’t use your shoulder because you’ll break it.’ ”

Has this had an impact on practical things, such as touring?

“Yes. I can’t do as much as I used to. On previous tours I could meet a hundred lawmakers in between shows and now I know I can’t do that. This tour is particularly demanding. Whether you have a face-off with your own mortality or somebody close to you does, you are going to get to a point in your life where you ask questions about where you’re going.”

Does that mean there won’t be another U2 tour after this one? “I don’t know. I don’t take anything for granted.” Bono has always lived in fear of the band being called a heritage act known for touring their greatest hits. Last year they went on the road with The Joshua Tree, playing the 1987 album in its entirety.

“It’s OK to acknowledge work you’ve done and give it respect, but if it’s the best we can do, then we’re not an ongoing concern,” he says now. Would his younger self be disappointed with his older self?

“I’m not sure that my younger self would approve of where I’ve got to, but I like to think that if my younger self stopped punching my face, my younger self would see that I’ve actually stayed true to all the things I believed in. I’m still in a band that shares everything. I’m not just shining a light on troublesome situations, but trying to do something about them. I still have my faith, I’m still in love, I’m still in a band. What about your younger self?”

My younger self would say you screwed up on life, you screwed up on love, you’ve been evil and destructive, but hey, you’re in a penthouse with Bono. My younger self would be: “Yay, you made it!”

Laughing, Bono turns to me and says: “You should be the singer of this band.”

Naked with Adam Clayton

I’m back in the Boston Garden arena. In the winding innards of the building, the U2 production team weave seamlessly. They do this every day and most of them have been doing it for years with a loyalty that’s unquestioning. Most of the production staff are women, women who get things done. They pad about in dark jeans and Converse.

I first ventured backstage with U2 a couple of decades ago. There was a different uniform then — a floaty maxidress and platform shoes, and women would run, not teeter, in vertiginous heels across stadiums.

I meet Adam Clayton in the guitar bunker beneath the stage. He gives me a tour. The Edge’s technician, Dallas Schoo, is lovingly poring over his 33 guitars. Clayton’s bass guitars are less in number — about 18 — but they make up for it in sparkle. He has given them names: there’s a lilac glitter guitar with a heavily studded strap that he calls Phil Lynott, after the Thin Lizzy frontman, and one with a more gothic strap that he calls the Cure.

Clayton is wearing a Vivienne Westwood T-shirt and sandalwood scent. His body is ripped, impressive. He likes to work out.

We part some makeshift curtains to do our interview, which will take place while he’s having his physio. Soon he is naked but for a towel. The physiotherapist is on tour with the band and Clayton gets his treatment before every show.

“I work out a lot. I run and do weight training in the morning, so that tightens me up, and then in the show, carrying the bass, there are various other occupational quirks that affect the body. I have to make sure they don’t develop into real problems. It was a bit of a shock to learn that the things you could do in your twenties and thirties in terms of being a player, when you get into your forties and fifties, they cause repetitive strain injuries.”

Does he mean carpal tunnel? He’s playing his bass and his fingers won’t move?

“Exactly. But actually for me more of an issue is what it does to my hips and lower back, shoulders and neck. You just get so tight that you can’t turn, you can’t move.”

Hagen, the physiotherapist, is German and he speaks with a German-Irish accent. He’s got strong hands that seem to know what they’re doing. Watching someone be massaged is quite meditative. “It is. You make sure that your channels are open when you’re on stage,” Clayton says. “You don’t want random thoughts coming through your mind.”

There was a time in the 1990s when he was full of random thoughts and random excesses. The polite gentleman went wild. He fell in love with Naomi Campbell. His man part was on the back cover of Achtung Baby, his inherent shyness replaced by rampant exhibitionism. He has come a long way since then. He is married to Mariana Teixeira de Carvalho, a former human rights lawyer from Brazil, and has a baby daughter, Alba. These days, his addictions end at exercise and designer T-shirts.

“When we started, from 1976 onwards the sound of the punk band was the most powerful thing a teenager could hear, and all the bass players were stars. It was much cooler than the guitar. We are also a little more mysterious at the back. These days, most modern records are programmed and synthesized bass and drums. It’s not real.”

He thinks the toll that playing has taken on his body is nothing compared to what it has done to Larry Mullen.

“He has to have physio an hour before the show and an hour after. He’s in pain and his muscles need to function. Drumming is the most debilitating thing you can do. It’s like a sports career, where you shouldn’t really be doing it past the age of 35, but nobody knew that when rock’n’roll started. Nobody realised it could be a long career.”

Three consecutive tours have had a cumulative effect, and Clayton is looking forward to a holiday “with the rest of the lads in the south of France”. They all have houses near to each other on the French Riviera. It’s extraordinary that they not only work together but also want to holiday together. “Yes, it’s perverse. Everyone now has children and there’s a group of friends that revolve around that, so it’s a community and it’s nice to spend time together.”

They all still like each other? “Yes, I still think that Bono and Larry and Edge are the most fascinating people in my life. They constantly surprise me in terms of their insight, their development, their intelligence. When you find people like that, you hang onto them.”

The band takes a chef on tour to make sure they eat healthily. “I’ve gone vegetarian. I’ve heard so much about the meat-processing business that I don’t trust anything. I’ve got high levels of mercury in my blood, so I don’t eat fish. I’ve not drunk for 20 years, and that was a completely different life, but I notice other people are heading that way. There’s now a theory that even one drink is harmful. I think that’s a bit extreme and a bit of a buzz wrecker, but it does seem that alcohol is being thought of as possibly causing cancer.”

Not very rock’n’roll, is it? But if old rock’n’roll was about living for the moment, the new challenge is longevity and not losing relevance.

No more touring?

Larry Mullen was the founder of the band and is still the heartbeat. Nothing happens without him. He also has a Dorian Gray thing about him. He has always looked much younger than his 56 years. He’s always fit and I’ve always loved those drummer’s arms. As we chat before the show, he tells me that these days those arms don’t come easy and neither does the drumming.

For Mullen, constant touring has been hard. In the 1990s, after a huge tour he simply took off on his motorbike and disappeared. It was some kind of reaction against the band and also an inability to cope with being home, but it’s long since been worked through. He’s had ambitions to further his acting career. “We’ll finish this and then there will be time to decide what we want to do next. I’d like to take a really long holiday.”

There’s something in the way he says it, not just tiredness, that makes me think maybe this really is it. “You never know. I assume there’ll be another album. I don’t know that anybody needs another U2 record or tour anytime soon. People could do with taking a break from us and vice versa.”

Will he try to resume acting? “I’d like to, but I had to put all that stuff on hold. The problem is if the tour gets changed, the album gets released at a different time and all bets are off. My agent said, ‘I can’t do this because you’re just not available,’ so I think I will re-employ the agent and tell them I won’t be doing this for a couple of years. I’d like to do something else.”

Shouldn’t the agent have kept him on the books? “Well, in fairness it was difficult. I wasn’t answering the phone.”

The perils of privilege

The next day we all travel from Boston to New York on Amtrak for three nights at Madison Square Garden. U2 have reserved an entire carriage for cast and crew. The Edge, with his wife and daughter, Sian, is the only band member on the train — the others all left after the gig last night to see their families. Yesterday was his 16th wedding anniversary. Did he give Morleigh a gift?

“You get special dispensation when you are on the road — she is with me and that is the best present.”

He’s very smiley when he talks about family and equally so on the subject of guitars. Does he really use 33 each night? “It’s possible.” In the early days, he only used one. Back then, Bono would hit some very high notes. “These days, we try to save his voice.

He has a good range. His top note would be a B these days, but he has hit C, which is what a top tenor would hit, and is very, very high. An opera singer would hit that maybe once a night.”

Earlier this month Bono lost his voice on stage in Berlin, and the show was cut short. He was back performing again three days later. I sense a strong concern for him.

“He has a very ambivalent attitude to his physical self. He doesn’t naturally take responsibility for his physical wellbeing. Which is fine in your twenties, but you get to a certain point … It is a difficult shift for him. If you spend too much time thinking you are old and past it, you probably can’t do it any more.”

We see passengers on the platforms peering in. Perhaps they can spot the odd vacant seat in our carriage and are wondering why they can’t get in. Being with the band is like being in a cocoon. You feel set apart, not so much alienated as special.

“I am not under any illusions that we are not to some extent institutionalized by being members of U2,” he says. “How could you not be?”

Sian is very smart and engaging. She appears in the show’s visuals and is also on the cover of the new album with Bono’s 19-year-old son, Eli Hewson. Last night in the bar, she and I bonded over dyslexia.

“I am sort of dyslexic when it comes to music,” the Edge tells me. “I am totally instinctive. I use my ear and am not technically proficient.”

The other night on stage, he looked perplexed when Bono said that he had gone off the rails. When did that happen? He laughs, knowing that it never has. The eyebrows arch as he briefly ponders just how devastating that would have been, not just for him but for the rest of the band.

“I have been pretty together through the years. I am sure we have all had our moments and lost our perspective and started to buy into the bullshit. That’s the hardest thing, to hold on to the perspective. The general rule is that everybody involved in any endeavour always overestimates their own importance while simultaneously undervaluing everyone else; once you realise that, you can start catching yourself.”

I tell him that I had to catch myself from feeling put out on the second night at the hotel when the U2 crew were only given a cordoned-off area in the bar, instead of the whole bar to ourselves like the first night. How had I become so arrogant in the space of two days?

“Good question. We all have that tendency to enjoy being made a fuss of. It’s a Seamus Heaney phrase, ‘creeping privilege’ — you have got to look out for it because it can turn you into a monster, or somebody who needs help, a victim. And you don’t want to be that.” He laughs his wise laugh.

“That is the good thing about being a band member, we all spot each other’s tendencies to go off track. We are peers and equals. Solo artists have no peers or equals.”

Do they actually criticize each other? “It generally doesn’t have to be said, it just becomes clear. That’s the nature of our band culture, things get figured out. There have been very few times when we’ve had to have what you might call an intervention. It’s what friends do for each other, because that’s what we are, a bunch of friends.”

It was their first manager, Paul McGuinness, who looked after the band for 35 years, who suggested very early on that the band should split everything equally. This levelling seems to have kept them together. So many bands split up because of egomania and rivalry.

“It was a piece of genuine wisdom. It took us about three minutes to consider and go, ‘Yes, that’s a good idea.’ ”

When the train pulls into Penn station, we head off in opposite directions. I’m already sad to leave behind the cocoon, my rock’n’roll family. What if this really is the end?

Story by Chrissy Iley / Source: thetimes.co.uk

Leave a Comment