It is more than halfway through the 2019 Formula One racing season and U.K. driver Lewis Hamilton is poised to win a 6th world championship – his third in a row. The 34-year-old enjoys a significant lead in the driver’s standings, and his team – Mercedes-AMG Petronas Motorsport – has set the pace to take yet another Constructors title.

Racing enthusiasts bemoan the sport’s predictability at times; the same drivers and teams consistently lead the field year after year – most notably Mercedes, Ferrari and Red Bull – while the rest settle for scraps of places and points. Many believe it is a mere matter of money; those with the most can afford more research, innovation and manpower – all of which lead to better on-course performance and results. Others point to solid management – both on and off the track – and the sheer skill of individual drivers.

Each side is correct, of course. At the end of race day, however, there is still plenty of high-speed excitement and drama – so much so that the sport continues to draw record audiences on-site, online and on television. Merchandise sales have never been higher, as hard-core fans throw their team hats into the collective racing ring.

“It’s big business,” says Sir Jackie Stewart over the phone from his U.K. office. “Make no mistake; there is a lot at stake at each race, and in each season, for everyone involved.

“Mercedes looks like the team to beat again this year,” he continues. “They have those cars running very well, they have a strong crew, and they have two excellent drivers in Hamilton and (Vallteri) Bottas.

“I am not sure what has happened with Ferrari. They looked like the favourites in pre-season testing, but it just hasn’t come together for them. Leclerc (Charles) has been quite consistent, however; he is a good young driver with a strong future ahead of him.”

Stewart, now 80, nods to another rising star; Max Verstappen of Red Bull Racing.

“Max is fast, and he is only going to get faster. He is aggressive out there, and he isn’t afraid to take the car right to the very edge of its capabilities. Because of that, he has had a few incidents – and some bad luck – but as he matures, he will likely be a world champion sooner than later.”

Winning, after all, is the name of the game.

“Yes, but it is more than that,” explains Stewart. “When you get right down to it, these are men, alone, in high-powered vehicles, making split-second decisions that will have a large impact on the lives of many people.”

“Yes, but it is more than that,” explains Stewart. “When you get right down to it, these are men, alone, in high-powered vehicles, making split-second decisions that will have a large impact on the lives of many people.”

Stewart knows something about having an impact. His racing resume alone is adorned with so many accolades and awards – including three F1 championships (1969, 1971, 1973) – that it would take several Wikipedia pages to document all of the details.

“I didn’t start out with a racing career in mind,” he admits. “Actually, I was a pretty good clay shooter as a young man growing up in Milton (15 miles west of Glasgow). I won a competition at the age of 13 and was invited to join the Scottish shooting team. I did fairly well with it.”

By the age of 16, Stewart had left school, due in large part to his then-undiagnosed dyslexia.

“It was a very difficult and unpleasant time. I was picked on and bullied quite a bit because of my condition. I remember feeling ashamed and guilty, though I had no idea why, nor what the problem was. I just assumed that I was stupid and unlucky.”

As fortune would have it, a chance encounter put his racing wheels in motion soon after.

“I was working on cars at my father’s garage,” he recalls. “He owned a dealership, and both he and my brother were involved in motorsports. The owner of one of the cars I had been working on offered me the opportunity to test, and later race, one of his vehicles. I finished 2nd in my first race, and in my second race I finished 1st.”

The rest, as they say, is racing history; the “Flying Scot” – as he would come to be called – worked his way up the grid of junior racing until landing a Formula Three ride with Tyrrell in 1964. A year later he made his F1 debut in South Africa, finishing 6th. That rookie season was highlighted by his first F1 victory at Monza, Italy.

From 1965 until his retirement in 1973, Stewart competed in 99 F1 races, winning 27. During that same period, he also took part in the Le Mans 24 Hours, the European Touring Car Championship, the Can-Am Series and the Indianapolis 500.

He was scheduled to complete his 100th F1 Grand Prix at Watkins Glen in 1973 – the final race of the season, and of his career – when his teammate François Cevert was killed during practice sessions. Out of respect for their fallen comrade, the Tyrrell Team withdrew from the race.

“It was horrific,” recalls Stewart. “I was the last of the drivers to pull up to the scene of the accident and I walked over to his vehicle. They had left him in the car, because he was so clearly dead.”

While great in its glories, the high-speed sport has not been without its share of tragedies; since 1952, dozens of F1 drivers have died behind the wheel. In Stewart’s nine years, he lost a handful of his closest friends to the perils of the profession.

“After François’ death, I realized that it was only a matter of time before I would be killed as well.”

“These accidents – these terrible tragedies – were senseless and violent and, as far as I was concerned, completely avoidable.”

After his own horrendous crash at the 1966 Belgian Grand Prix – Stewart was trapped in his fuel-leaking car – he began exploring ways to make the sport safer.

Over the next decade, and despite much opposition, he lobbied his fellow drivers to pressure the sport’s governing bodies, owners, track officials and others, to implement new safety measures, including modernizing circuits, the fitting of barriers and run-off, improved medical facilities, as well as better trained and better equipped on-track marshals.

“It just kind of took off after that,” he notes. “The sport really shifted its focus to improving safety conditions – for the drivers, the crews, the fans – and we have only had a few fatalities since then.

“You see, we had the money and the technology and the resources – all we needed was the will and the consensus to make changes.”

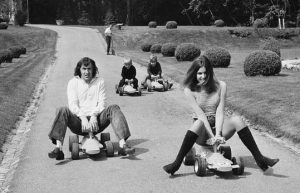

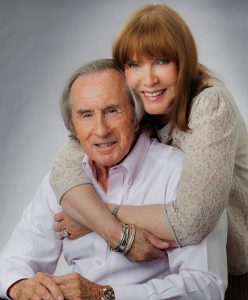

Stewart’s passion for motorsports is perhaps only eclipsed by his adoration for his beloved wife Helen. The childhood sweethearts married in 1962, later raising two sons, Mark and Paul.

Helen (née McGregor) has been at Stewart’s side throughout his career; first during his tenure as a driver, and later as he plied his trade as an F1 team-owner, as a sports commentator for various television networks, and as a celebrity spokesman for a number of public and private initiatives.

“She is as much a part of my story as I am,” he says. “Without her, I wouldn’t be the man I am today. She is both the love of my life and my best friend.”

In 2014, Helen – now 78 – rolled her Smart car near the family home in Ellesborough, England.

“Physically, she was fine,” shares Stewart. “A few scrapes and bruises and what not, but no major injuries. What was baffling, however, was that she showed absolutely no recollection of the accident. It was as if, in her mind, it never happened.”

Upon the advice of medical professionals, the couple visited the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota later that year. It was there that Helen was diagnosed with Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) – a cluster of progressive disorders that affect cells in the brain’s temporal and frontal lobes. The condition usually strikes people in their middle years but can afflict anyone of any age at anytime, impacting mental skills for communication, reasoning, social awareness and memory. The changes in personality and judgment eventually leave the person feeling confused and helpless.

“Honestly, I knew very little about dementia at the time,” confides Stewart. “I remember asking the doctor, ‘Ok, so what is the cure?’ and he told me there wasn’t one. I was simply stunned. ‘What do you mean there is no cure?’”

After the initial shock, Stewart suited up and put the pedal to the metal. Helen was relocated to the couple’s specially equipped apartment on the shores of Lake Geneva, Switzerland – just down the road from a private hospital – where she continues to receive round-the-clock care from some of the world’s finest doctors and nurses. He then began researching the disorder, meeting and networking with neuro specialists and other professionals around the globe.

“What struck me the most was how little attention dementia was receiving in comparison to other major illnesses.”

“The amount of funding and public awareness for cancer is astounding. And look at what we were able to do with AIDS; at one time, not very long ago, this disease was at the forefront of public attention and seen as a death sentence. And while there is still no cure for AIDS per se, through huge funding for research and treatment the illness has become much more manageable and people afflicted with HIV are now living longer and healthier lives. Surely we can do the same thing with dementia.”

The numbers on dementia are indeed staggering; it is estimated that 50 million people around the world are currently afflicted with the disease, and one in three people born today will develop the condition in their lifetime – meaning a new diagnosis every three seconds.

Driven by a desire to make a difference, and the lifelong love for his wife, Stewart formally launched Race Against Dementia (RAD) in 2018.

“It took a couple of years to get all of the pieces in place,” he explains. “If we were going to do this, we were going to do it right. It is a culture shift – a change in paradigm and the way we view the disease – so it will take time.”

According to the organization’s website, “Race Against Dementia raises and allocates funds to accelerate global research and development in the race to find a prevention or treatment for dementia.”

The not-for-profit group identifies four key areas to fulfill its ambitious mandate; New Talent – identifying and financially backing the most talented early-career researchers;

Innovation – providing catalyst funding, enabling researchers to pursue higher risk, innovative ideas that might not get funded by the mainstream; Speed – aiming to instil a ‘Formula 1 attitude’ in attention to detail and urgency, to accelerate the pace of solutions development; and Global – forming strong alliances with research centres of excellence on a global basis.

RAD has already partnered with both Alzheimer’s Research UK and the Mayo Clinic to drive the initiative. A Board of Directors is in place, and Stewart has drawn upon his lifelong friendships with the likes of past and present F1 drivers Emerson Fittipaldi, George Russel and Lando Norris to help raise awareness.

“Much of our philosophy comes from what I witnessed in my years with Formula One.”

“The dedication to research, the use of leading-edge technology, the commitment to innovation, and the importance of mentoring. We actually have PHD graduates working alongside people at McLaren and Red Bull to share best practices and better understand processes.”

Like F1, funding is key.

“Our initial goal was to raise $2.5 million. We have already far surpassed that amount, and the contributions continue to grow significantly each week. The pace has really picked up.

“Like it was with the safety issues in Formula One all of those years ago, we have the money and the technology and the resources – all we need is the will and the consensus to make changes.”

Though he continues to travel the globe for RAD and other commitments, Stewart is in constant contact with his wife.

“When I am not at home, I speak with Helen three or four times a day by phone. It isn’t easy; while her long-term memory is quite strong, her short-term memory is declining. So, even though we may have spoken in the morning, she might not remember our discussion when I call again later in the day.”

He is comforted in knowing that, even in his absence, she is well-cared for.

“Along with all of the medical help, Helen is surrounded by family members and friends. There is no shortage of company or love. And, when I am home, we try to get out to dinner and events with people a couple of times each week.”

Stewart is not unaware of the challenges faced by families of those afflicted.

“It takes quite a toll; emotionally, mentally, physically and, of course, financially. We are in a very fortunate position in that we can afford to have a team of professionals on-site every day. Helen has 24-hour-a-day attention from a total of seven nurses, with two working at a time. The average family today simply can’t afford that kind of care.”

He notes that what they can do is educate themselves on the disease, access local and regional resources, attend or create support groups, and contribute more time and money to the cause.

“And it is vital that we keep the conversation going with our family members, friends and others who are going through the same experience.”

“Most importantly, though, we must show our love and support for the people in our lives who are living with this terrible disorder.”

“What Helen needs most are lots of hugs and kisses and reassurance. I hold her hand as often as I can. I talk to her. I tell her jokes. We laugh and cry. She needs to understand that, no matter what, I am by her side and that everything is going to be alright.”

It is said that great leaders make others better by their sheer presence. And it was another great man, Martin Luther King Jr., who noted that a “genuine leader is not a searcher for consensus, but a molder of consensus.”

“We need as many people involved with this project as possible,” says Stewart. “The only way we are going to take the chequered flag on this is if everyone is clear on what the goals are and how we are going to achieve them.”

The similarities between his work in F1 safety and RAD are obvious, and Stewart has been as driven in his approach to each as he once drove the world’s greatest circuits – with purpose, passion, precision, performance and persistence.

“People,” he adds with a long pause. “This is a race against time. Not just for Helen, but for millions of people around the world, today and in the years to come. It is a race that we can and must win.”

Read: Jackie Stewart; Winning Isn’t Everything ~ The Autobiography

Watch: Weekend of a Champion

Leave a Comment