Lesley Choyce arrived in Atlantic Canada more than 50 years ago and has lived to tell the tale.

Well, I think the first hints of my love affair with Nova Scotia began somewhere back in seventh grade in Cinnaminson, New Jersey. As unlikely as it sounds, one of my teachers asked us to pick a Canadian province and give an “oral report” to the class even though we all hated the very idea of an oral report. It meant standing in front of the class, nervous as hell, and me with sweaty palms, reading out our research from 3 x 5-inch note cards.

Foolishly, perhaps, I chose to do my report on Saskatchewan because the name sounded funny, and I was attracted to the yellow colour of that large oblong province on the classroom wall map. Now, I don’t mean to belittle Saskatchewan, and I am sure it is a wonderful place to live, but my research led me to believe that it was a fairly boring place, known mostly for growing wheat. Nonetheless, I dutifully presented my findings to a captive but bored audience and took my seat only to be upstaged by my classmate Lance presenting a truly impassioned speech about – you guessed it, Nova Scotia.

While I never really liked Lance himself – a blowhard teacher’s pet who raised his hands often with great enthusiasm to answer math problems on the blackboard – he blew me away with the information he delivered. For here was a Canadian province with a gloriously rugged rocky coastline, lacerated with a seemingly infinite number of coves and inlets, where some residents still spoke a foreign and nearly forgotten language (Gaelic) and that was once its own nation (well, colony, really). Fishermen sat on old wharves smoking hand-carved pipes retelling yarns of yesteryear to each other. Off the shores of this magical place, those same fishermen or their sons could catch lobsters the size of Volkswagen bugs. And, of course, the province was once the home of what Lance called “bloodthirsty pirates.”

In short, this Maritime province was the land of my dreams.

I went home and devoured all there was to find in our family WorldBook Encyclopedia which made contemporary Nova Scotia sound like it was a half century behind the rest of North America with its quaint fishing villages, pet oxen, church suppers, and unpaved roads. I assumed that most towns looked just like Peggy’s Cove and that all the children there dressed like little street urchins from a Charles Dickens novel. At this tender junior-high age, I had convinced myself that I had been born into the wrong century and lived in the wrong part of the world. So, I guess you could say that I cultivated my yearning for this sacred place from afar as so many love affairs begin that way.

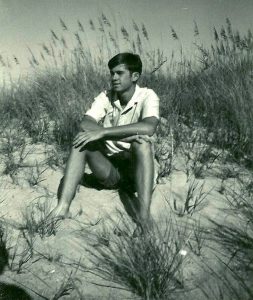

During high school, however, I decided that Nova Scotia was unattainable, at least for now and, besides, I had grown to rather like my own home turf and my contemporary corner of the twentieth century due to my growing interest in South Jersey girls, cars, and everything related to the surfing craze that had swept the American nation. And, oddly enough, all these three things were attainable right where I lived. I won’t say categorically that surfing was number one on that hit parade list, but it was pretty far up there.

During high school, however, I decided that Nova Scotia was unattainable, at least for now and, besides, I had grown to rather like my own home turf and my contemporary corner of the twentieth century due to my growing interest in South Jersey girls, cars, and everything related to the surfing craze that had swept the American nation. And, oddly enough, all these three things were attainable right where I lived. I won’t say categorically that surfing was number one on that hit parade list, but it was pretty far up there.

But then, one humid summer night in a Presbyterian church auditorium on Long Beach Island at the Jersey Shore, I attended the viewing of 16 millimeter surf movie and in the final six minutes of the film, the narrator said something like, “And far to the north on the East Coast of North America is a place virtually untouched by the surfing world where frigid crystal blue North Atlantic waves wrap around pristine headlands for some of the best point breaks to be found anywhere.” And, sure enough, there were images of two surfers in black wetsuits surfing head-high waves peeling perfectly right to left as if from a goofy-footers dream come true.

I don’t know why I didn’t drop everything – girlfriends, plans for university, Vietnam war protests, summer job, and financial ambition – and drive my ‘57 Chevy north to the promised land. But I didn’t. I dutifully went to my first year of university in North Carolina and then back to New Jersey even as those images of immaculate northern surf continued to burn in my memory vault.

And then, near the end of the summer of 1971, my surf buddy and bass player from my teenage rock band, the Wipeouts, Jack, reminded me we had some free time before fall classes started. So, we did it – we drove north through New England in his Volkswagen Kombi, crossed the border into my first foreign country and headed “down east” to the shores of my beloved province.

Our first stop was Crystal Crescent beach, not far from downtown Halifax. Today this beach is known for its water being crystal clear, but also because part of it is a nude beach which I urge you to steer clear of if you are taking your kids there for an outing to the sea.

Sadly, for Jack and I, there were no waves this fine day of our arrival, but we did come across a pair of those young Dickensian boys that were dressed like little old men and spoke in a funny accent. They were scouring the headland for something called pigeon berries, which turned out to be small hard black berries that tasted bitter and sour and were notably perhaps only truly fit for the pigeons to eat.

Nonetheless, we hiked the shorelines and admired the granite outcroppings, the ragged spruce trees shaped by winter gales, and we were mesmerized by the swaying coppery-coloured seaweed dancing in the unpolluted ocean.

All that coastal beauty soon created a tremendous thirst which sent us two wandering pilgrims to downtown Halifax where we ambled into a nondescript tavern where thin bald men in flannel shirts and wearing white aprons walked among the patrons hefting extra-large trays of overflowing beer glasses at shoulder height. We seated ourselves at an empty table and surveyed our surroundings. In the dim light, amidst the smell of stale beer and stale urine, we noted that the floor was actually covered with sawdust, the tables were as sticky as kindergarten mucilage, and that there were no women in the place, only men. I would later learn that, for the most part, at that time in Nova Scotia, most bars were just for men. Some would have a separate section where women could imbibe, or most were happier to just associate with other women at such establishments as The LBR or Ladies’ Beverage Room.

When asked by the server what we’d like, I assumed he wanted to know what kind of beer. That one, I said, pointing to a particularly seductive glass on his tray. “Ten Penny, then,” he said. “How many?” “Two each,” Jack piped up, not wanting us to look like wimps in front of the rowdy though cheerful room full of rough and ready Nova Scotian men.

The beer tasted funny to us, having been accustomed to the American varieties of Pabst Blue Ribbon, Ballantine, and Iron City. It was also higher in alcohol leading us to believe that Nova Scotians, possibly even all Canadians, were more robust and hardier than our fellow countrymen. Ten Penny suited us just fine, as it turned out. And so did Schooner beer, Alpine ale, and a strange thick black liquid known as stout.

Not long after our nocturnal Haligonian adventures, we were back on our search for waves and, at long last, we did our first paddle out on the west side of the Lawrencetown Headland, about 20 minutes east of Halifax by car. The water was colder than we were used to and clear with more swaying kelp that – to a sandy beach break surfer from New Jersey – seemed like a crowd of exotic dancers.

I suppose I should be reporting things here about the culture, the people, or the politics of the province although it was our interest in surf, girls, and beer that dominated our attention. Somewhere while driving down Highway Seven on the seemingly forgotten, remote Easter Shore, we saw a sign for a store that called itself New Scotland. It had not occurred to me, odd as that may sound, that this had anything to do with the name of the mystical land we were exploring. (And both the WorldBook and Lance had failed to report this important bit of knowledge.) Jack, being a better student of dead languages than myself, said, “Of course, you didn’t know that? Get it? Nova means new. Scotia means Scotland. It is Latin.”

And so began my personal and professional interest in the culture and history of my beloved province that eventually led to me writing a complete history of the place called Nova Scotia: Shaped by the Sea which Penguin books would publish and distribute around the world. Given my poor grades in high school history, the fact I took no history courses at all in university, and that I was a lowly immigrant from New Jersey, such a scenario seems unlikely. But suffice to say that one’s passion for a parcel of coastal geography can do that to writer. Or at least it fired me up to eventually learn everything I could about Nova Scotia.

So, there we were, two rambling surf lads driving down gravel roads to empty beaches and even emptier surfable waves with me dreaming about someday living here.

It felt like home to me, and I grew to believe, or at least fantasize, that I had almost certainly lived here before in another life.

If that is true, I am sure I was a sailor of some sort and that I had once stood on the deck of a heaving ship looking shoreward singing, “Farewell to Nova Scotia, the sea bound coast. Let your mountains dark and drear eye be.”

I tried explaining this to Jack and he just shook his head and said I should focus more on finding the next point break and maybe lay off the Ten Penny Old Stock Ale.

Ignoring the latter bit of advice, we found ourselves at a very rural tavern somewhere along the wilds of the Eastern Shore where watering holes were very few and far between. I realized that we were doing a poor job of getting to know the locals or learning anything much about the people and the lifestyle, so I struck up a conversation with an old fella in a John Deere ball cap. My father had always told me not to strike up conversations with strangers about politics, but I often did. I started the conversation, however, asking the man some silly generic question like “What’s it like living here?”

He, of course looked at me like I had just arrived from Mars or one of the more distant outer planets and answered succinctly with as little effort as possible, “It’s quiet.” From there I moved on to asking him about his job, only to learn he was unemployed and that it was due to “the government.” He was referring to both the federal and provincial government and that all politicians, he claimed, were corrupt.

Jack offered up the universally accepted notion that it was the same where we came from.

“Which is where?” Mr. Deere asked.

I explained that we were from New Jersey, and he couldn’t understand why we had wanted to come to Nova Scotia. When we told him we came here to surf he stated flatly, “But there’s no surfing in Nova Scotia,” a statement I would hear for many years after I’d been surfing here.

I moved the conversation back to politics and asked about local elections and how one got elected. He explained that whoever promised to pave the most roads got elected, but I thought he was joking. “Well, in some places here about, they still get elected the old way.”

“Which is?” I asked.

“Well, buddy comes are round to your house or stands outside the community hall on election day and hands out a mickey of rum to the men or a box of chocolates to the women. Whoever has the best goods tends to win.”

“Isn’t that illegal?” Jack asked.

“Not that I know of,” he answered as he took his last slug of foamy brew and announced that it was great chatting with us foreigners but that he had to get home to “the wife.”

Somewhere along the way on our continuing journey, we encountered excellent fiddle music, which also enhanced my emotional ties to Nova Scotia. Before long, I could tell the difference between a lament and a strathsprey.

For unknown reasons, Jack and I had come to the conclusion that since there were so few people on the Eastern Shore, and those few we encountered were so friendly, that there must logically be no crime here at all. Thus, we left the van unlocked and with windows open as we paddled out at a delightfully remote place called Clam Bay Beach where the seaweed was so thick it slowed the waves as they approached and made surfing there seem like we were cruising across walls of the most wonderful mush.

For unknown reasons, Jack and I had come to the conclusion that since there were so few people on the Eastern Shore, and those few we encountered were so friendly, that there must logically be no crime here at all. Thus, we left the van unlocked and with windows open as we paddled out at a delightfully remote place called Clam Bay Beach where the seaweed was so thick it slowed the waves as they approached and made surfing there seem like we were cruising across walls of the most wonderful mush.

Why I had left my wallet sitting right on the dash absorbing summer sunlight, I can’t recall, but when we returned to the van, dripping heavenly saltwater from every square inch of us, someone had stolen money from my wallet.

Not all my money, mind you.

I am sure I had a total of $50 in my wallet and whoever was the thief took exactly half. Yep. Just half and left the rest. And, as strange as that may sound, it made me love Nova Scotia that much more.

Leave a Comment