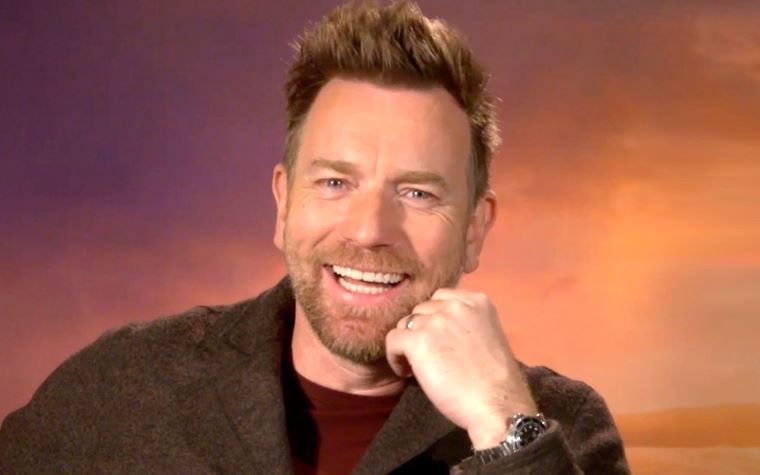

It’s not easy to hang out with Ewan McGregor. The plan at first was to spend an afternoon together in Los Angeles. His publicists finally were able to find me a window, and then: McGregor eloped. Vanished for two weeks. When he showed up again, he needed to appear on Jimmy Kimmel Live! We finally speak, the morning after the show, and it’s all coughs between smiles – the whole household has COVID. “It’s a fucking nightmare,” McGregor says, over Zoom, apologising for his absenteeism. All of this had followed an aggressive stomach bug, before that, a bad cold. And then there was the wedding, which wasn’t really an elopement as much as a ceremony so private, so unannounced, even his publicity team had been caught unaware.

If Ewan McGregor’s schedule is in disarray, it’s because he is – not for the first time – in the middle of a moment. In September he won his first Emmy, for his starring role in the Netflix miniseries Halston. Prior to that, he was nominated for Fargo.

Lately, he’s been making head-turning appearances in small films (The Birthday Cake) and giant ones (Harley Quinn: Birds of Prey). He completed Long Way Up in 2020, a third motorcycle adventure series with his friend Charley Boorman, this time driving electric Harley-Davidsons from the southern tip of Argentina to Los Angeles. McGregor, now 51, has a new baby at home – he and his new wife, the actor Mary Elizabeth Winstead, had a son in June last year. “With COVID, you want to go to bed, but we’ve had to keep going because we have the baby,” he says, laughing under his breath. “It’s just nasty.” And then there’s Obi-Wan Kenobi, which has reunited McGregor with his most famous role, and the frothing fanbase of the Star Wars universe.

It’s been 17 years since McGregor and George Lucas made the prequels – 1999’s The Phantom Menace, 2002’s Attack of the Clones, 2005’s Revenge of the Sith. If what you remember about them are the bad reviews, worse dialogue, and endless Jar Jar Binks jokes, all I can say is: why, hello there. Over time and across the internet the prequels have been reassessed and – at least among Star Wars fans – become beloved, canon, the source of fan art, animated series, and endless memes. A lot of fans, especially young ones, consider McGregor’s films superior to the more recent sequels (The Force Awakens, The Last Jedi, and 2019’s The Rise of Skywalker), which were plagued by director changes and incoherence. The volte-face even changed how McGregor thinks about the films. “The [prequels] weren’t well received,” he says. “What you hear is usually critic-driven, and everyone was very negative. As it transpires, we were creating the relationship I had with Star Wars when I was a kid with this [younger] generation.”

“I didn’t know,” he adds, “but now I do.”

When McGregor was six, he and his brother were taken to see Star Wars at the cinema because their uncle, Denis Lawson, was playing the rebel pilot Wedge Antilles. “We couldn’t believe it was in our cinema,” he says. “On top of that, it was Star Wars. It must have just blown my tiny mind.” McGregor was born in Perth to a pair of teachers. He moved to London when he was 18 to study drama and got the starring role, four years later, in Channel 4’s Lipstick On Your Collar. Then, in 1996, came Trainspotting. Some people said his performance as Renton was “dry perfection” (The New York Times). Some said he was “the weasled remains of a contemporary Alfie” (The Guardian). Either way, it seemed like Hollywood had found its new leading man.

Has anyone seen everything McGregor? I tried for a month – I might be the first American to watch Blue Juice – but came up short. He’s performed in nearly 100 films and episodes of television. I saw him first when Shallow Grave played in my college town’s local cinema. I saw Trainspotting on a trip to London in 1996. At that point, he was still assuredly Scottish to the audience, but there have been endless roles since with little or no connection to his background – enough to make him seem vaguely international on-screen, unrecognisable from Renton, even rootless. (McGregor became a US citizen in 2016.)

Any back catalogue so big has high and low points. Mainly he’s the lead, occasionally the support. Sometimes he’s excellent and so is the film: Trainspotting and Moulin Rouge!, gems like the Beginners and Last Days in the Desert. One constant is a kind of boyish cheerfulness, a good-humoured faithfulness, whether he’s an object of affection (I Love You Phillip Morris) or an asshole (Down With Love). He can be a terrific villain (Jane Got A Gun, Son Of A Gun), and not just in films with the word “gun” in the title (Birds of Prey, Haywire). Sometimes the film is a clunker (Zoe), or just absurd (A Million Ways To Die in the West), or so stacked with talent (August: Osage County), it’s hard to make an impression. A look through McGregor’s career is a study in what it takes to lift screen acting from passable to great.

“If I’ve ever done anything that didn’t come from a burning need to do that play, that part in that film, then it’s never been my best work,” McGregor says. “Not because I didn’t try harder, or try hard enough. There’s something magical about that: the need to do something. When you read something and you go, ‘this has to be me.’”

The film critic David Thomson has a new book coming out next year called Acting Naturally. He cites McGregor’s voice as one of his top assets as a performer – how, in many roles, it enables him to reinvent himself in a way that breaks free of the British idea, according to Thomson, that your voice identifies you, restrains you. “He would’ve done very well in the ’30s and the ’40s,” Thomson says. “He has a faith in a sort of valiant forthrightness. There’s a lot of optimism in his screen persona. He seems to be having fun in a way a lot of actors don’t seem to these days.”

“I never find the acting of anything hard,” McGregor says. “I have just been doing it a long time, and I trust myself. Before I was even doing it, I was sort of arrogantly self-assured. I’m not like that about lots of things in my life.” He pauses and clutches the back of his neck. “That said, if you were to speak to Mary, two weeks before I started Halston, I was shitting bricks. There’s something about approaching a role – you feel like you’ve got to do it all. So I am both of those things: I’m a nervous wreck, and I’m absolutely self-assured. But I forget before I start filming that I’m self-assured.”

McGregor likes to turn things over. He’ll say a thing one way, reconsider, try something else. Adjust himself on the sofa, stroke his beard. It’s both self-assured and reassuring. Call it likeability: the kind of charisma that makes a leading man. In my month of watching him, I started to notice how often McGregor’s characters are nearly killed in a number of his films. He looks to be hit by a car at the end of The Ghost Writer. At the end of Haywire, by Steven Soderbergh, he’s left to drown. His character is killed by his brother in Cassandra’s Dream, but the gore is left up to the imagination. As if McGregor is too charming to murder in front of a big crowd.

I mentioned to Thomson that I was trying to guess where McGregor’s career would go next, if Halston and Kenobi suggested different paths or the same one. McGregor’s performance in both promotes a type of determination in the face of wretchedness, a fuck-off to time, a youthfulness no matter a character’s age. “Youthfulness is a big part of him,” Thomson says. “He’s very clever and competent. I imagine he’s fun to be with – he gives that feeling.” He adds, with a touch of concern, “I’m not sure what he’s going to be like when he’s 60.”

“I’ve had a few moments where I’ve thought about doing something and going ‘There’s not much point, I probably don’t have time,’” McGregor says, shaking his head. “Yeah, so that’s a weird one.”

We end the interview waving at each other through our computers, with plans to meet after McGregor returns from a press tour in Europe. It must be exhausting, I think as I shut my laptop, to be likeable all the time.

When Kenobi begins, Obi-Wan is hiding from the motherlode of midlife crises, though we’re actually not sure how old he is. “We’ve never put an exact age,” Deborah Chow, the series director, says, laughing. “Around Ewan McGregor-age-ish.” Kenobi is a broken man. Traumatised. Most of his friends are dead, and the calling to which he’s dedicated his life looks to be destroyed. “He’s trying to live a normal, small life and he’s lost,” McGregor says. “He’s carrying a lot of grief. He’s carrying a lot of pain. He’s tormented by this guilt about losing Anakin [to ‘the dark side’] and not being able to stop that from happening. So that’s where he is. And that’s where we started talking about it.”

Initially, Kenobi was meant to be a film. Five recent Star Wars movies crossed the billion-dollar mark in worldwide release: The Phantom Menace, The Force Awakens, Rogue One, The Last Jedi, and The Rise of Skywalker. But Solo, a 2018 spin-off, did a mere US$390 million – which is a lot of zeroes to add up to a disappointment, but it was the first Star Wars movie to lose money. So, the powers-that-be at Lucasfilm and Disney turned the franchise toward smaller screens and stories, which has so far yielded The Mandalorian, the anime-tinged Visions, and The Book Of Boba Fett, with Andor and Ahsoka still to come.

“I actually love a limited series,” Chow says. Before Kenobi, she directed two episodes of The Mandalorian. “It’s a great format for doing a character story, in a similar way to how they’ve done things like Logan or Joker, where you take one character out of a big franchise and really get more in-depth. Obi-Wan is so iconic – everybody loves this character. But there was still so much to be explored.”

Unlike the prequels, McGregor is both star and producer on Kenobi, meaning he was more involved in decision-making. The series was filmed using the StageCraft system, a new filming technology created for The Mandalorian by Industrial Light & Magic. In lieu of green and blue screens, it encircles a film set with high-definition video walls to create a backdrop for performers to respond to. McGregor and other cast members from the prequels have spoken publicly about their frustrations with the earlier screen work. At that point, the tech was cutting-edge but isolating, offering little to conjure chemistry. “The more we went through the three movies I made with George, the less I was surrounded by anything,” McGregor recalls. “I was on a blue screen for weeks or months, talking into thin air, and it’s hard. It’s just hard to do.”

On Kenobi, the set was more alive. “It made us feel like we’re there. When you’re in the spaceship, the stars are flying past you and it feels real. I felt something very old Hollywood about it – it reminded me of those images of Hollywood in the ’20s or ’30s, where they had a row of sets. An actor would be playing a scene here, there’d be another actor there. It was like that, just super hi-tech. It’s insane.”

“The way they shoot, it’s not computer graphics – they’re real aliens,” Kumail Nanjiani, one of McGregor’s co-stars, says. “They have masks controlled by remotes. You’re doing a scene and there’s aliens with nostrils flaring, and it’s wild. It looks like Star Wars.”

McGregor first learned he’d been cast in the prequels while filming Velvet Goldmine, Todd Haynes’ 1998 movie about glam rock in ’70s Britain. “It was a huge departure from what I was doing. You think of those two films…” Maybe Disney should bring out an Obi-Wan Kenobi action figure in disco gear, I suggest. “Yeah, in leather flares and nothing else. There’s a lot of homoerotic Obi-Wan/Hayden [Christensen] fan art that gets sent to me now and again. I don’t know how it finds me. It’s always a bit of an eye-opener. You open the envelope, you think you’re going to have to sign something, and you’re like, ‘Fucking hell!’”

The idea of returning to Star Wars has hung over McGregor for more than a decade. “Years ago, there was a time everybody would end every interview with, ‘Are you going to do porno?’” McGregor says. My jaw drops. He laughs: “Irvine Welsh wrote a sequel to Trainspotting, which was called Porno. And everyone asked if I was going to do that, and would immediately follow up, ‘And what about Obi-Wan Kenobi, would you play him again?’ I did a bit of social media then – I don’t anymore – but I would see it constantly, this question, are you going to do it again? Are you going to do it again?”

“With Ewan and Obi-Wan, he and the character just feel seamless,” Chow says. She saw the new series as a bridge from the Zen master originated by Sir Alec Guinness to the more emotional character crafted by McGregor. “Obviously [Ewan] was a producer on Kenobi, he’s more than just an actor. But he’s lived with this character. Not only did he play it in the prequels, but he’s asked to live with the public persona of being Obi-Wan.”

If there’s a burden in that, McGregor doesn’t appear to feel it. He is delighted with Kenobi and ready to go again. “I really hope we do another,” he says. “If I could do one of these every now and again – I’d just be happy about it.” His prequels co-star Hayden Christensen returns in the series as Darth Vader, but this time in full regalia. In the movies they made, the character didn’t yet merit a helmet – and the first time McGregor did a scene with Vader in full costume, “I got a jolt of fear that made me six years old again,” he says. “I’ve never experienced that before. I just about crapped my pants.”

About a week after our first conversation, McGregor and I meet at Bike Shed LA, a motorcycle club in the arts district, an offshoot of the London branch in Shoreditch. (McGregor’s friend Boorman is an investor.) It’s a massive space with a bar, a restaurant, a tattoo parlour, a barber’s. Everywhere are vintage motorcycles, Indians and Triumphs and Moto Guzzis. McGregor arrives on a Kawasaki Concours 14 in a white T-shirt, blue jeans, and boots. He’s just returned from the press tour. Up close, his forehead is lined, but he doesn’t look tired. We sit in a quiet booth in the corner. As lunch arrives – we share pork ribs and chicken wings – he says, “I don’t ever see any sort of through-line in my work. Of course, it’s your job to look for that. But I really don’t.”

This was a theme of our conversations, that if McGregor has entered a new phase in midlife – new show, new success, new marriage, new child – it’s not by grand design. He can be erratic, he says. He works by feeling. He can be accused of doing too much. I point out that for work he is constantly in front of cameras; and when he’s not acting, he and his best friend disappear for months to ride bikes and be vulnerable in front of yet more cameras. He returns to the idea of being on a journey, regardless of the destination. In our first conversation, he told me that he and Boorman had trouble initially selling their motorcycle show to networks because they wanted it to be about an epic quest – and that was it. “We couldn’t believe the sort of ideas that people wanted to slap on top of it. To make it a TV show to them, it had to be something else. And we were adamant that the journey is enough.”

I wonder if the journey is different when it’s constantly being documented. That being present in a moment perhaps isn’t the same when everything’s being filmed. “You do have to be comfortable with everything being captured,” he says. “And there are times where, when it gets stressful or something goes wrong, the last thing you want is a camera in your face. But that’s where the good stuff is.”

In our first conversation, we talked about what it’s like to be famous and to be a fan. I wanted to know if the two ever overlapped, if there was a moment when, despite his success, his visibility, he’s still one of us. McGregor says he used to be crazy for the band Oasis. “If you spoke to anybody who came around my house in the ’90s, it would always end up with There and Then, the video where they walk out and Noel’s got the Union Jack guitar. That went on after dinner and would bore everyone to death. I was in my twenties, but I was like a 14-year-old fan. It was kind of embarrassing.”

I tell him I’d been a big fan in the ’90s of the films he did with Danny Boyle – Shallow Grave, Trainspotting, the underappreciated A Life Less Ordinary. Those movies defined a zeitgeist. What had it been like to be one of the faces of that period – what was it like when the moment was done?

“It felt amazing to be Danny Boyle’s actor,” he says softly. He likened the relationship to the collaboration of US actor Martin Donovan and the director Hal Hartley, who cast Donovan in half a dozen films. “I thought, ‘I’m that to Danny.’ This is who I am, and it made me feel so great. Because I felt Danny Boyle was changing British cinema, and I was part of it.” Then Boyle cast Leonardo DiCaprio, rather than McGregor, in 2000’s The Beach. The two of them didn’t speak for years. McGregor has said he felt rudderless. He drank too much, partied too much. Constantly recognised in the street, in clubs: the highs and lows of a dream come true. “There’s something about the excitement of the fact that it’s happened which is hard to contain. I don’t know how well I did or didn’t contain it. I just know that my relationship with it is very different now.”

McGregor seemed not to regret those years, but happy to have survived them. (He and Boyle patched things up and resumed their friendship before making T2 Trainspotting in 2017.) “I don’t feel like that guy anymore. I don’t have the same relationship with my fame. That’s to do with age and experience, also just a realisation of what works and what doesn’t. At that time, there was a hedonistic side to my life, which ended up not suiting the rest of my life.”

In the restaurant, he rolls his shoulders forward and stares intently when he listens. He doesn’t seem bothered by people identifying him, but does nothing to draw their stares. I ask if the character roles he chooses now, like Halston and Fargo, even Kenobi, make him happier than less complex parts – the action tropes many Hollywood actors might more easily slip into. “They’re more of a challenge,” he says. “I’m still just looking for the most interesting thing to do next. If you read an action hero on the page, there’s not much to play. But in actual fact, I’d quite like to do a full-on action film. I like all the training, I like the fighting.” He laughs. “So I actually am looking for a fucking action role to play.”

In addition to his new son with Winstead, McGregor has four daughters with his ex-wife Eve Mavrakis. If there is a constant to his performances, he says, it’s being a father. The absent dad in Nanny McPhee Returns. The haunted father in American Pastoral, which he directed. “I felt like it was a love letter to my girls,” he says. “A dad film, really.” One of his daughters, Jamyan, is adopted; McGregor met her for the first time when he and Boorman visited a shelter for Mongolian street children during Long Way Round. McGregor has been an ambassador for UNICEF since 2004, and he and Boorman often visit their programmes during their expeditions.

“People talk about mental health, mindfulness,” Boorman tells me. “Today, when you talk to your friends, you don’t just ask, ‘How are you?’ You say, ‘How are you, really?’ Ewan’s always been like that.”

McGregor had mentioned that he recently made a film with his oldest daughter Clara – You Sing Loud, I Sing Louder, a film she conceived and developed with a screenwriter. They shot it last autumn in New Mexico, and it’s currently in post-production; when we meet, McGregor hasn’t talked about it publicly before. He became involved in the project a few years ago, when he saw Clara in New York City. “She tells me that she’d come up with an idea about writing about us. At first I was a bit nervous. I didn’t know what that meant.” The story would be a road trip: a father driving his daughter to rehab. “I got the script while I was making Halston. I sat down to read it and I was blown away. It was a beautiful story about us. There’s things that aren’t accurate, or are bent, but they still reflect our estrangement for a while.”

Did you drive your daughter…

“To a facility? No, that’s fictional. The drive is fictional. But for a couple of years, we sort of lost her. So the storyline is about her realising that she needs the help her father’s trying to give. Along the way, their relationship is healed somewhat.” He looks at me, pained, but also joyful. “I was so impressed by the story, by the humour. There’s a sort of recognition in it that made me very proud and at the same time very close to her. I felt like she understood more than I’d thought.”

Like a recognition of your position.

“My position, but also stuff about parenting somebody who’s in trouble. It’s a fucking horribly difficult situation to be in. You’re so scared of what can happen. You will do anything in the world to stop losing them.”

The film was shot with a small crew. He loved the production’s modesty, the relationship between him and his scene partner. “We play father and daughter,” he says. “It’s a reflection of us and our story. I was really impressed with her as an actor. It was just the most remarkable experience to be acting with her.”

Do you see ways that she is as an actor that reflect how you are as an actor? “I do. Because she just allowed herself. We didn’t discuss the scenes too much beforehand. And that’s what I’m like. I’m not very interested in talking about stuff before I do it.”

McGregor is suddenly vulnerable. “A divorce in a family is a bomb going off in everyone’s life – my children’s lives,” he says. “The sort of healing of that is ongoing.”

None of this is easy for him to talk about. It isn’t his inclination. For the amount of time McGregor spends in front of cameras, he is a private person who doesn’t crave attention. I remember something Nanjiani told me, from working with McGregor, “When the cameras aren’t rolling, he’s just Ewan. It really struck me, one specific moment, he had a very emotional scene, and in between he was hanging out. I said, ‘Do you need a moment?’ He was like, ‘Nope.’ Some people you work with want to pull focus. He sets you up.”

I approached this article wanting to know what it was like, sitting on the metaphorical rumbling motorcycle that is a film star’s career, to look back and see dozens of roles behind you. What it feels like to try to envision what’s next. McGregor is entering his third decade of being an artist. He is aware of getting older, that not every option is on the table anymore.

Lockdown changed his perspective. It had been decades since he’d spent seven or eight months in a single place. “I just want to be present. I don’t want to be away for four months in Romania. If it has to happen, maybe it has to happen, but I’m trying really hard not to do that,” he says. “Before, I just felt like a gypsy. I was always a dad first, but I was away a lot.”

McGregor has made California his home. He misses Scotland, being close to family, but Los Angeles is where his life is right now. We leave the club and walk out into a spring day in Southern California: cloudless sky, not too hot.

As we leave I ask McGregor if he has a sense of what type of actor he’ll likely be in the coming years. From my own experience, middle age can lead to self-acceptance, make you care less about what other people think, but also lead to new appetites and new ideas. “I don’t know,” he says. “I’m quite excited about it.” He thinks about it more. “I’m going to name-drop: I remember meeting Terry Gilliam…” He’d been sent a script. For more than 20 years, Gilliam had been trying to make a version of the film that became 2018’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. “He says, ‘What the fuck have you been doing all this time? You’ve been underplaying everything. What happened to the guy in Trainspotting? What happened to that guy?!’ It was quite rude. It’s rare that somebody challenges you. But it stuck with me.” As though he had taken the criticism on board. And the work now is maybe more free, even cathartic.

“Like when you were talking about Fargo and Halston. These are much bigger characters, and I really enjoy it. At the same time, I really enjoyed doing the thing with Clara,” McGregor says. “I was totally myself.”

Story by Rosecrans Baldwin / Source: gq-magazine.co.uk

Leave a Comment