Nobody could break your heart like Sinéad O’Connor. There was the song, of course – Nothing Compares 2 U. And the video with the single tear falling down her cheek. There was her ethereal beauty; the angelic skinhead. But what broke your heart most of all was the troubled soul – the love, poetry, intelligence, pain and madness, all scrambled and inseparable.

Last time I interviewed her, in 2021, she told me she’d been in a psychiatric hospital for the best part of six years. But Sinéad, who died on Wednesday aged 56, would never call it that. She reclaimed the politically incorrect and unsayable, and spat out the words joyously. “I’ve spent most of the time in the nuthouse. I’ve been practically living there for six years.” She stressed that it was her privilege to call it that, not mine. “We alone get to call it the nuthouse – the patients.”

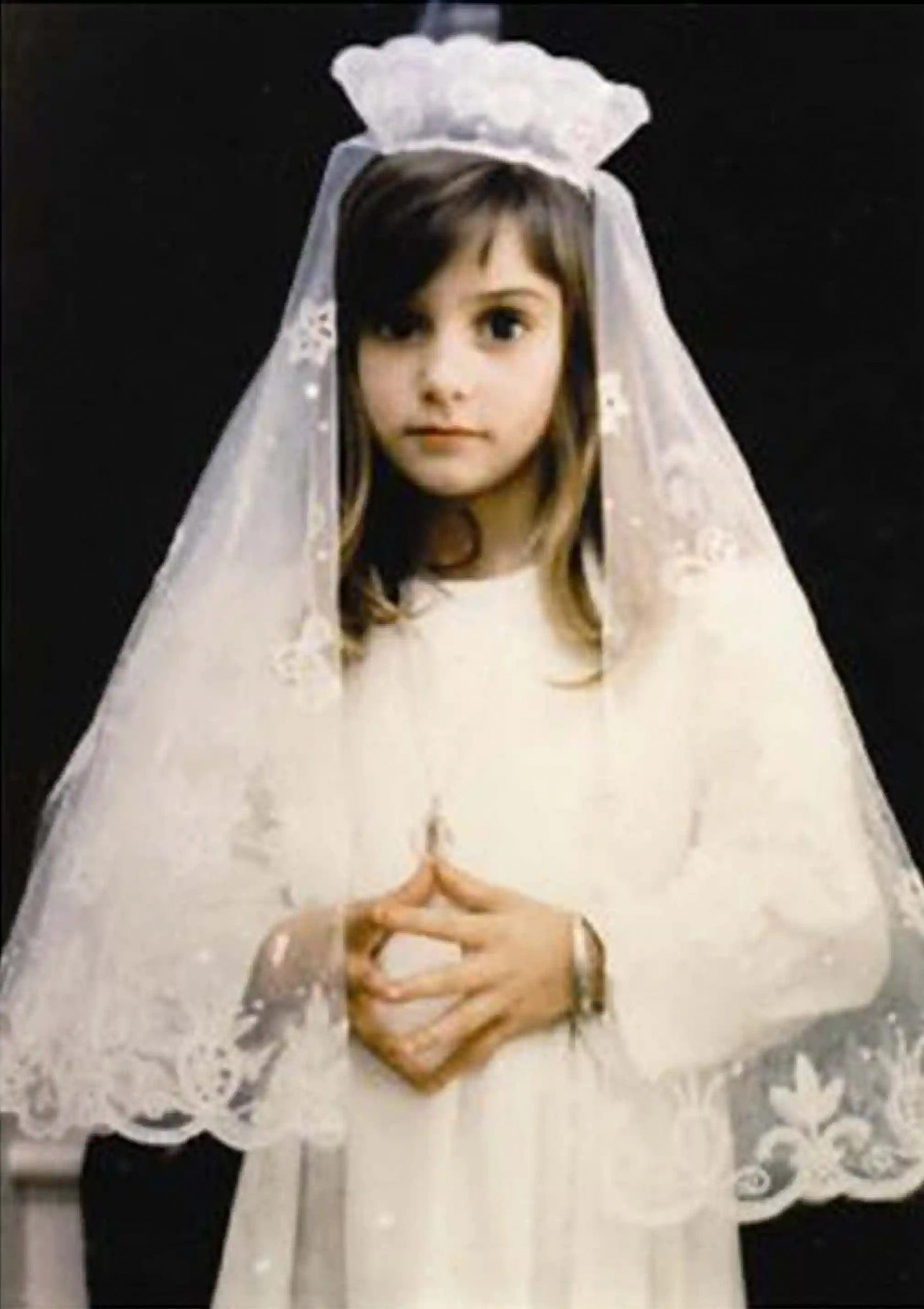

I interviewed Sinéad twice. The thing you always had to question was whether she was in a fit state to be interviewed or whether it might be exploitative. The answer was never clear. We had other connections. My friend John went out with her when they were in their twenties. She had a thing for men called John. A few weeks ago, he was clearing his house, preparing to move, and he came across a picture of them when they were a couple. She was so young and alive. The picture seemed full of hope and uncertainty.

The first time we met was in Bray, just outside Dublin, in 2010. She had become a priest; her face was rounder and she wore a tweed suit. She had the air of a mid 20th-century industrialist. We were talking because Pope Benedict XVI had just issued an apology to the victims of decades of sex abuse by Catholic priests in Ireland. Eighteen years after tearing up a picture of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live as a protest at abuse in the church, she’d been vindicated. Despite everything she still had her faith. I asked if she’d been ordained to stick two fingers up at the Catholic hierarchy. “No,” she said, “I didn’t do it to cause offence. It was just something private between me and the Holy Spirit.”

That day she talked about her mother’s abuse – physical and sexual. She always talked about it. She told me she’d won a prize at school for rolling into the smallest ball and that the reason she could do it was because she was so used to having the shit kicked out of her by her mother. Not surprisingly, she never got over it.

That day she talked about her mother’s abuse – physical and sexual. She always talked about it. She told me she’d won a prize at school for rolling into the smallest ball and that the reason she could do it was because she was so used to having the shit kicked out of her by her mother. Not surprisingly, she never got over it.

Sinéad had converted to Islam, changed her name to Shuhada Sadaqat, but was still chain-smoking and potty mouthed.

She also talked about her bipolar diagnosis and how medication had helped. She asked if I’d ever seen a cowboy movie where the guy is shot from behind and a huge hole is blown through his back: “That’s how I used to feel. I felt like I was walking round the world with a huge fucking hole in me. And within a day of taking the medication, I felt the cement had come and filled in the hole.”

In 2021, we talked for hours during lockdown on Zoom. She was at home in Wicklow, sat by a pipe that remorselessly drip-dripped as day turned to night. Sinéad had written a memoir of sorts called Remembering. It was beautiful – elliptical, poetic, gorgeous sentences scattered among the debris of her life. She compared the Ireland she grew up in to Iran: “a theocracy, slightly less potent but the same situation.”

And again she talked about her mother. Marie was a kleptomaniac who forced her daughter to steal for her. They would collect money in charity boxes, then Marie, who was killed in a car crash when Sinéad was 18, would steal all the donations – sometimes as much as £200 a night.

Sinéad had converted to Islam, changed her name to Shuhada Sadaqat, but was still chain-smoking and potty mouthed as ever. For her, the word “fuck” wasn’t so much a swear word as a form of punctuation.

Sinéad had a brilliant way with words. Even at her bleakest she’d make you laugh. She moaned about her nonexistent libido. “I don’t even look at policemen’s arses any more,” she said sorrowfully. She told me one of my favourite jokes (I’ve got a feeling she also told it to me the first time we met): “I went to the doctor. He told me to stop wanking. I said, ‘Why?’ and he said, ‘Because I’m trying to examine you.’” She was beyond irreverent.

Most of the time, though, she wanted to talk about Shane, the youngest of her four children by different men. She was devastated that he had been put in care after her hysterectomy. She told me he had become a drug addict and dealer. Shane was the love of her life. She felt guilty and angry and fearful for him. We couldn’t mention it in the piece because there was an injunction in place.

Sinéad reminded me of George Michael – supremely gifted, screwed up, hilarious and terrifyingly vulnerable. Like Michael, she rarely gave interviews, but when she did she really talked. Over the following days she texted obsessively – more info, another anecdote about her mother (“One evening some friends of M called round – she gave them dog food on toast and told them it was paté”), pleas not to misrepresent her, and an order not to make it too bleak: “Don’t make it all misery. Just remember, my story’s not Angela’s fucking Ashes.”

After it came out, she rang to say she was pleased – there were some jokes and it wasn’t a misery-fest. Next thing I knew she’d told a journalist that I’d exploited her. I phoned her, asked her what her problem was. She apologised and said she hadn’t meant to include either me or the Guardian in her criticism. Classic Sinéad.

We kept in touch. Last January, Shane killed himself at the age of 17. When I heard, I feared the worst for her, as many of us did. A few weeks later she texted. “Hey Simon, it’s Sinéad … my son whom I told you about when we spoke … he took his life five weeks ago. I’m just letting you know …” She wanted to write about his life for the Guardian. “We can figure out how best to go about it. So that it ends up being productive. No grief porn, I mean. Something useful …” She sent emojis of herself in her grey hijab making a power fist. She never did get to write about Shane for us.

In one of her final messages to me she wrote: “I’m OK … strong little cuntress.” And she was – though ultimately not strong enough. Perhaps the most heartbreaking thing about her dying so young was its inevitability.

Story by Simon Hattenstone / Source: theguardian.com

Listen to the article here;

Touching remembrance Simon. Thank you.

Curious, do you know if Sinead was put on hormones after her hysterectomy? Seems her mental health plummeted after that in 2015.

I am a medical person and deal a lot with women and hormones. I joke,Hormones R Us. Many women suffer severe psychic disturbance when their hormones are ripped away after a hysterectomy, esp in their 40’s.

I sure hope she was on them.

Woulda, shoulda, coulda…. bleaker world without this brilliant woman.

she talks about it in an interview with Dr Phil. identifies herself that she had mental health issues related to hysterectomy, poor after care and no hrt

Sinead was so unique. One time artist that looks like an angel and sounds like nothing I have ever heard. Thanks for that article.

Thanks you love❤️

I loved this article it was so honest, Sinead was so much like a dear friend of mine who also suffers from Bi Polar like her he was extremely talented, his poetry would bring a tear to the hardest eye, like her he was totally honest fascinating, handsome, being in his company was filled with fun and laughter he like her was a maze of contradictions. Without his condition he would be far too ordinary, Sinead will never be forgotten, that beautiful face will always be in our minds eye R.I.P sweet soul……………