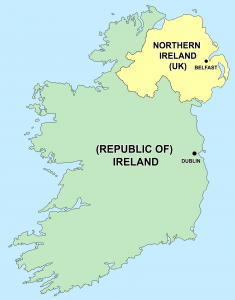

Northern Ireland, having been blessed for so long with an uncomplicated border with the rest of Ireland, is about to gain a second border. The British government is to immediately start erecting border structures at three of Northern Ireland’s ports: Belfast, Warrenpoint and Larne. The border ports are being established to facilitate the checking of goods passing between Great Britain and Northern Ireland from early next year when Brexit comes into effect. The border ports formalise the separation of Northern Ireland’s customs regime from the rest of the UK. How long can the North maintain a porous border with another jurisdiction to the south and a customs border with the rest of the UK? As they say in Westerns: ‘This town ain’t big enough for the both of us…it’s you or me’.

The shock for unionism of a customs border with the UK being installed really should be no shock at all. In a ground-breaking meeting near Liverpool last October, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar agreed that such a border needed to be established. In so doing, Johnson betrayed the Democratic Unionist Party that had propped up his Conservative Party’s government through a Confidence and Supply Agreement since June 2017. More fundamentally, Johnson betrayed unionism since no unionist party would have agreed to border checks with the rest of the UK under any circumstances. Johnson proceeded regardless.

What makes the new border still harder to bear, from a unionist perspective, is that its inception coincides with two landmark court judgements that seem to militate against unionism. The first being on the case of a Derry woman, Emma de Souza, who won the right in court to confer Irish/EU residency rights on her American husband. Initially, the British Home Office denied de Souza’s right to do so on account of the UK exiting the EU. Her victory establishes the legal precedent that non-EU spouses of people from Northern Ireland have the automatic right to reside there—as they did before Brexit. While the UK government has now imposed a June 2021 deadline for applicants to avail of this right, it is not at all clear how the government can deny the right after that deadline. After all, de Souza won her case on the principle enshrined in the Good Friday Agreement that people in Northern Ireland have the right to be Irish or British or both. That principle will still obtain beyond June 2021. The precedent of this case, in effect, provides that Northern Ireland will have a different immigration regime to the rest of the UK.

So, a customs barrier with the UK, but a less complicated immigration system than the rest of the UK—you win some, you lose some? Well, that depends on what you consider a victory. It is paramount to unionism to prevent a divide down the Irish Sea and both of these developments appear to force such a wedge.

So, a customs barrier with the UK, but a less complicated immigration system than the rest of the UK—you win some, you lose some? Well, that depends on what you consider a victory. It is paramount to unionism to prevent a divide down the Irish Sea and both of these developments appear to force such a wedge.

That brings us to the second far-reaching court judgement. Adding salt to unionist wounds, a ruling on May 13th the Supreme Court of the UK found that Gerry Adams’s internment in the 1970s was illegal. The Detention of Terrorists (Northern Ireland) Order 1972 required a Secretary of State sign-off. Since the highest British authority in Northern Ireland at the time, Willie Whitelaw, did not authorise Adams’ internment without trial it was illegal. (Whitelaw did not authorise hundreds of other internments either and consequently they were illegal too). Unionist ire rapidly ensued. The Ulster Unionist Party leader Steve Aikens took issue with Adams’ contention that internment was ‘a blunt and brutal piece of coercive legislation’ on the grounds that victims of the IRA’s campaign had no right of redress when the IRA murdered them. Aikens ignored the fact that hundreds of innocent people were illegally interned (some were tortured). In any case, internment remains incontrovertibly brutal and it was also politically stupid.

Even the pandemic seems to be working against the unionist cause. Three of the four nations of the UK (Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales) are at variance with England in their response to Covid-19. Northern Ireland unionist politicians have sensibly aligned with Northern nationalists—and with the rest of Ireland—in maintaining the strategy of lockdown in contrast to England where lockdown is being considerably phased out.

And there is more. On May 6th the Welsh Assembly became the Welsh Parliament, 21 years after its foundation. Presiding Officer of the newly renamed Welsh Parliament Elin Jones said: ‘Now, more than ever, our citizens expect a strong national parliament working for Wales…With full law-making powers and the ability to vary taxes, the new name reflects the Senedd’s constitutional status as a national parliament’. The renaming may be largely symbolic, but it is symbolic of secession in a UK that badly needs a narrative of unity. The establishment of a national parliament is happening at a time when three out of four of the constituent parts of the UK identify less and less with the UK’s policies on the biggest health and economic threat in living memory.

The Northern Ireland Assembly is now the only legislative governing body left in the UK: Scotland, Wales and the UK as a whole have parliaments. It is not in unionists’ interest to advocate upgrading it to a parliament in Northern Ireland because it would appear to deepen the cleavage with the rest of the UK that is fast becoming a chasm. Nationalists do not particularly want a parliament either: the memory of the original Parliament of Northern Ireland that represented a travesty of their political identity and civil rights endures. Besides, the nationalists tend more towards an all-Ireland political structure than to entrenching themselves in Northern Ireland. Just now, the momentum is unerringly going that way.

Maurice Fitzpatrick, May 2020

Leave a Comment