A novelist, an artist and a historian rallied Scots to turn their richly woven history into literal cloth. Canada has an equally colourful tale to tell – if we have the imagination and the will.

Writer Arthur Herman’s notion that the Scots “invented the modern world” may be a tad fanciful, but there’s no debating that the folks who devised – among a great many other things – the telephone, the steam engine, malt whisky and the Canadian confederation (Sir John A. Macdonald being Glasgow-born), from time to time do come up with some inspired ideas. One of the latest is the Great Tapestry of Scotland. There’s a strong argument to be made that this is one nation-building initiative that Canadians would do well to consider emulating.

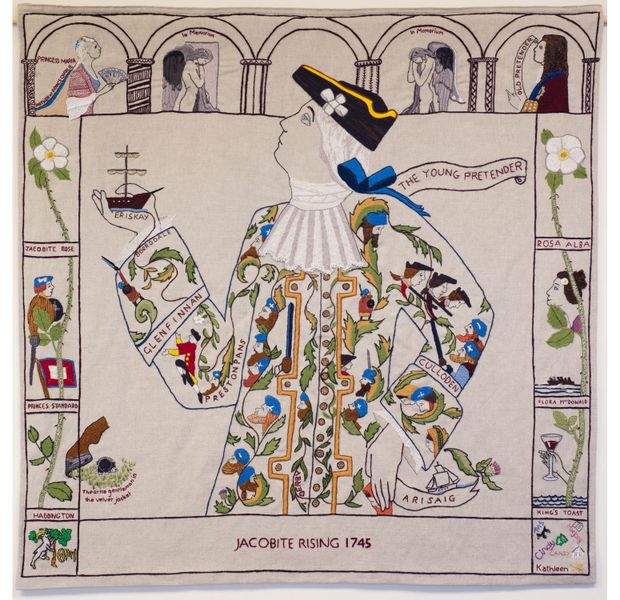

If you haven’t heard of it, the Tapestry is a work of textile art that chronicles the history of the land of kilts and bagpipes in 160 meticulously embroidered panels. The initiative is the brainchild of Scottish author Alexander McCall Smith, of No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency fame. It came to him one day in late 2010 as he was viewing an Edinburgh exhibition of the Prestonpans Tapestry, the 104-metre-long embroidery that commemorates the 1745 battle in which Jacobite leader Bonnie Prince Charlie routed an army of the Hanoverian king George II of England. “I’d heard good reports of the Prestonpans Tapestry, but I had no idea of the sheer impact it would have on me,” Mr. McCall Smith says. “I became completely engaged in the story it was telling.”

The author, who’s a champion of all things Scottish, is nothing if he’s not inventive. While viewing the Prestonpans Tapestry he thought, “Why not create an even bigger tapestry, one that would depict the entire history of Scotland?” And so, in a rush of the kind of enthusiasm that’s his mien, he immediately set to work.

By the end of the day, Mr. McCall Smith had recruited artist Andrew Crummy to design the tapestry that he now envisioned. Mr. Crummy’s graphic style is well-suited to pictorial storytelling. He had won plaudits for his designs of the Battle of Prestonpans Tapestry and a Scottish Diaspora Tapestry, and for his creations of vibrant wall murals that depict the history of Scottish various cities, towns and places. Mr. Crummy comes by his inspiration and sensibilities. His late mother, artist Helen Crummy, was a well-known community activist and author. “I learned about a community art ethos from my mother. It’s all about believing that everyone is creative, and if you can get people to be creative together, new things start happening,” Mr. Crummy says.

By the end of the day, Mr. McCall Smith had recruited artist Andrew Crummy to design the tapestry that he now envisioned. Mr. Crummy’s graphic style is well-suited to pictorial storytelling. He had won plaudits for his designs of the Battle of Prestonpans Tapestry and a Scottish Diaspora Tapestry, and for his creations of vibrant wall murals that depict the history of Scottish various cities, towns and places. Mr. Crummy comes by his inspiration and sensibilities. His late mother, artist Helen Crummy, was a well-known community activist and author. “I learned about a community art ethos from my mother. It’s all about believing that everyone is creative, and if you can get people to be creative together, new things start happening,” Mr. Crummy says.

“I knew that what [Mr. McCall Smith] was proposing was a bit of a jump for me. But it struck me as a fantastic project. I was keen to be involved, and so I immediately said yes.”

Next, Mr. McCall Smith contacted well-known Scottish historian Alistair Moffat. He, too, was keen to be involved. “I thought it was a great idea,” he says.

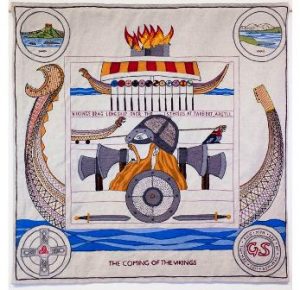

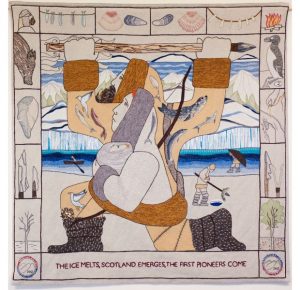

Being a social historian, one who speaks all of Scotland’s languages – English, Scots and Scottish Gaelic – Mr. Moffat has written widely about almost all periods of Scottish history and not just about the stories of the powerful or notable. He’s also a self-described “ruthless editor.” Those attributes made him an ideal choice to choose the subjects and craft the kind of freewheeling historical narrative for the Tapestry that Mr. McCall Smith had in mind.

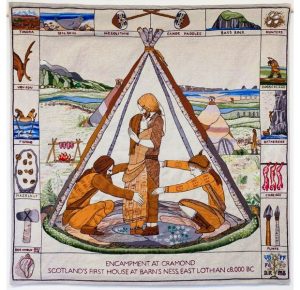

“It’s all very well talking about the whole sweep of Scottish history, but a country’s story can be a minefield when it comes to selecting what should be included and what should not,” Mr. Moffat says. “One thing was clear: The history that engages people today is the history that reveals the day-to-day life of ordinary people – not just of those who were in positions of power or privilege.”

With an artist and an historian on board, the Tapestry project began picking up steam. Dorie Wilkie, an embroiderer extraordinaire, pledged her involvement, as did other prominent people in the Scottish arts world, academia, government and business. By early 2011, the Great Scottish Tapestry Charitable Trust had been set up, and the £350,000 (approximately $600,000) project was off and running.

Mr. McCall Smith, collaborated with Mr. Crummy and Mr. Moffat to create a historical narrative and a master design for the Tapestry. Once that process was complete, Mr. Crummy drew a series of postage-stamp size preliminary sketches that were circulated to the Tapestry trust’s board members. Their comments and other input informed the artist as he produced working drawings, each one about a metre square. Those images were then transferred onto linen. Says Mr. Crummy, “I was careful to leave blank space on the outer edges of each panel. This allowed the stitchers room for individual expression, to put their own marks on the panels.”

Politician Tricia Marwich, the then-presiding officer of the Scottish Parliament, made the first stitch in September, 2012, and then thousands of stitchers in cities, towns and communities from all parts of the country set to work. The numbers associated with their handiwork in what became the greatest “community arts project” in Scotland’s history – and perhaps anywhere – are inspiring.

The volunteer stitchers collectively spent 100,000 hours stitching 480 kilometres of wool yarn onto 200 metres of linen. The use of a variety of wools created the colours, shading and texture that imbue the Tapestry with stunning vitality.

The end result is a historical legacy project that’s inspiring, educational and a delight to behold. It’s also the world’s longest tapestry, although purists will tell you that technically it’s not a tapestry. Rather, it’s a stunning feat of narrative embroidery “in the same tradition as the Bayeux Tapestry” – the 11th-century Norman artwork that depicts events leading up to the 1066 conquest of England.

The Great Tapestry of Scotland toured Scotland in late 2013, with the 4½-year excursion wrapping up in July. During this time, the Tapestry attracted more than 400,000 visitors. (Unfortunately, among them was a thief who in September, 2015, stole a panel that depicted the Apprentice Pillar in the medieval-era Rosslyn Chapel – which figures prominently in author Dan Brown’s 2003 bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code. Fortunately, Mr. Crummy and the seven original stitchers who created the ornate panel were able to make a duplicate.)

The rush to view the Tapestry will resume in 2020, when it settles into a permanent home in a refurbished post office in Galashiels, a historic town in the border area southeast of Edinburgh.

“We’ve all learned a lot from this experience,” Mr. McCall Smith says. “Many of us have learned a bit of history; many of us have learned about the desire that people have to engage in joint creative activity with others. Everyone, I think, has learned that what might seem a ridiculously ambitious project can succeed if there’s enough love and enthusiasm and courage about. And there was.”

The histories of Scotland and Canada admittedly are dissimilar in many ways; however, there are many common threads. For one: Just as the Scots are striving these days to define their country and shape its destiny, Canadians are struggling to do the same.

If ever there was a time for Canadians to pause, take stock of who we are as a nation, reflect on how we got here, soothe simmering regional differences, further the process of reconciliation with Indigenous people and – hopefully – to plot a course for the future, it’s now. An inclusive, grass-roots initiative to create a Great Tapestry of Canada could be just the spark that’s needed to ignite such a process.

If ever there was a time for Canadians to pause, take stock of who we are as a nation, reflect on how we got here, soothe simmering regional differences, further the process of reconciliation with Indigenous people and – hopefully – to plot a course for the future, it’s now. An inclusive, grass-roots initiative to create a Great Tapestry of Canada could be just the spark that’s needed to ignite such a process.

Who might champion such a project is a question that remains to be answered. But two things seem certain. One is that Canadians, like Scots, would have “enough love and enthusiasm and courage” to see a project of this sort through to completion. And two is that we’d have no shortage of subject matter or intriguing historical personalities to include in a tapestry of our own.

In my mind’s eye, I already can see colourful panels depicting the myriad narrative threads, controversies and all, of Canada’s richly complex history, sprawling landscape and diverse peoples. The only limits to the stories waiting to be told – if there are any – would be those of our collective imagination.

Story by Ken Cuthbertson / Source: Globe & Mail

Ken Cuthbertson’s most recent book is The Halifax Explosion: Canada’s Worst Disaster.

Leave a Comment