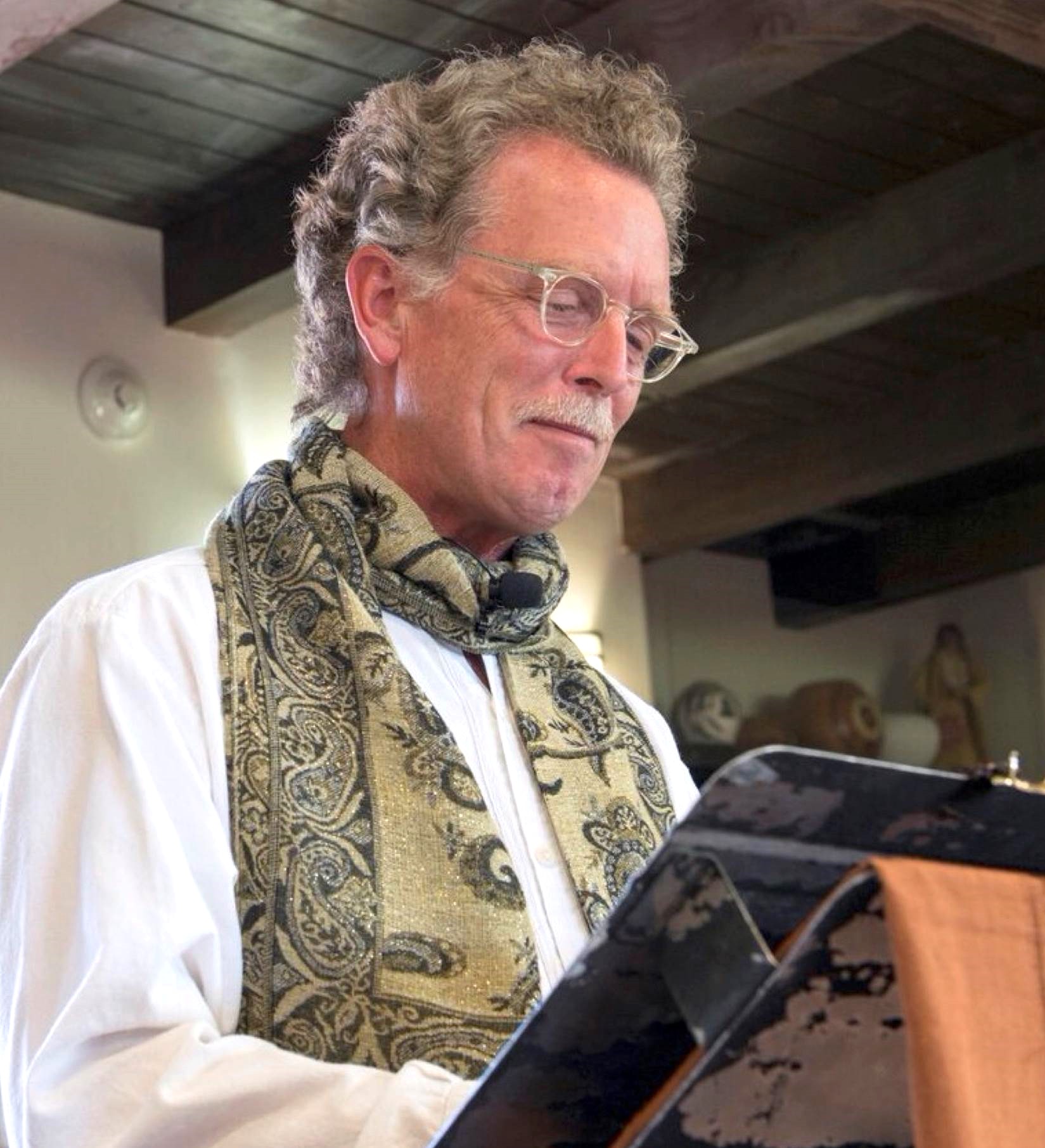

The Reverend Dr. John Philip Newell is considered the foremost authority on Celtic Spirituality alive today and has been described as “a wandering teacher” with “the heart of a Celtic bard and the mind of a Celtic scholar.” Recentl we spoke with him from his home in Edinburgh

You have Canadian roots?

Yes, I’m Canadian born. My father was from Ireland, and my mother was from Scotland, but they met in Canada, and that was where I and my sisters were born. But I feel sort of equally at home on both sides of the Atlantic.

You’re generally considered the foremost authority on Celtic spirituality, and certainly on Celtic Christian spirituality; where did your own interest in spirituality begin?

I was reared in quite a conservative evangelical family tradition, religiously. For which I’m grateful. I mean, I don’t see myself as being there in any sense now, but I think what it gave me was a very strong awareness, or sensitivity, to the heart. At its best, it is a tradition that pays attention to the heart so. I often think, when I’m involved in interfaith dialogue, that I continue some to bring some of that tradition. I realize when I’m meeting with a rabbi, or an imam, or a native teacher, what I’m doing, first and foremost, is looking to the heart. I’m very interested in ideas, and historically, the formation, development, and unfolding of ideas. But I realize I’m very much a man of the heart. But that tradition did not give me a sense of the presence within Earth, and within the natural realm, but my experiences did. As a boy growing up in Canada, when I look back on those years, I realized that I was being attentive to the mystery, to this sort of mystique of Earth. But they didn’t yet have any sort of language for religious or spiritual language. It was when I came to study theology in Edinburgh in the mid-1970s that I first heard George McLeod speak publicly. He was in his early 80s, I was early 20s, and it was the first time in my life I had heard a Christian teacher speaking about the sacredness of Earth and speaking also about the way of non-violence as the way of true relationship, both individually and collectively. Hearing him that evening here in Edinburgh, there was this sense of coming home. I hadn’t even realized that that’s what I was looking for when I heard him, I realized he was addressing something deep in my soul that hadn’t found articulation or expression. Although I was only in my early 20s, I realized I need to somehow get close to this man. I need to know more and learn more about what I was hearing. And a few weeks later, I was on Iona and bumped into the great man, and that was really a pivotal point on my own path. It wasn’t that I didn’t have the experience of sacredness in relation to Earth. It was more that I didn’t have language to give expression to it. I think that continues to be an important aspect of what I’m doing. You know, in my journeys and travels and teaching in different locations, I think what I most cherish is when people will say things to me like, ‘yes, I know this to be true, but I hadn’t heard it,’ or, ‘I hadn’t been taught it.’ That’s my understanding of it, of being a teacher or writer, and that is that I’m giving expression to what’s already in the soul of the listener. So, to that extent, I think it’s very much the same. I was coming into spiritual articulation, through George McLeod, and I think that’s what I’m trying to do in my work now.

I guess that begs the question; what is spirituality for you today?

I guess that begs the question; what is spirituality for you today?

I think very, very close to the heart of my sense of spirituality is that it’s a way of seeing – seeing the spiritual at the heart of the material, or seeing spirit within all matter. A way of seeing that translates into action, a vision of reality that can, at this urgent time of need in humanity’s journey, move us back into loving earth and loving the true essence of one another. I think it’s that love that is the fire of real transformation and change. So, I see spirituality as articulating a way of seeing, an articulating that leads to compassionate action.

Your own studies have taken you through the works of Carl Jung as well.

Yes. Currently, I am finishing the details of a book which I am calling The Great Surge: Turning to Earth and Soul, and The Quest for Healing and Home and – as I did with Sacred Earth, Sacred Soul – I’ve taken nine prophetic figures from the past and allowed their wisdom to speak into this moment in time. So, I’m the teacher as someone who transmits wisdom, rather than necessarily seeing myself as a fountain of wisdom. I would prefer to see myself as transmitting wisdom from those who’ve gone before us, trying to speak wisdom in new ways for today, and one of the great figures that I’m drawing from in the new book is Carl Jung.

Where does creativity come from?

In the Celtic world, one of the phrases that I love and find in many teachers throughout the centuries is, to speak of the soul within the soul. That’s where I would say creativity comes from. We’re made of the divine, and that dimension within us is longing to be creative, longing to give expression to what has never been expressed.

In your opinion, why is Celtic spirituality important today? Is it maybe more important now than ever?

Well, I think the two essential visions that come out of the Celtic tradition – and I’m speaking about a lineage of wisdom that we can trace back to the 1st century in the Celtic world and the Celtic Christian tradition – is consistently about the sacredness of Earth and the sacredness of every human being, and it is those two principles or visions that we’re tragically out of touch with as a Western world, as nations in this critical time. So, for me, it is very much about accessing a storehouse of wisdom from the past, a tradition with deep roots in action as well as vision; roots that are based in meditative practice and prayer, as well as commitment to engagement and to speak that wisdom into this moment in time. I’m a son of the Christian household. A couple of years ago, I relinquished my ordination as a Minister of the Church of Scotland because I realized there was virtually no connection between what I was teaching and writing, and what I signed up for as a young minister in my 20s. No connection between my teachings and the historical creeds and confessions of Western Christianity. I still see myself as a son of the Christian household. I’m deeply grateful to stand in in the wisdom of Jesus’ tradition. But I don’t, for the most part, see the Western Christian tradition speaking profoundly enough into the matter of sacredness of Earth in every human being. I mean, I’m not a Celtic fundamentalist. I’m not suggesting that everyone needs to become a Celtic Christian, but I think that this tradition does have some great treasure for this moment in time. That’s why I’m passionately giving myself to it.

It’s mandatory if we are going to survive the current crisis we have.

Yeah. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the writings of Thomas Berry, the eco-theologian. With a name like Berry, I’m assuming that he has some sort of Celtic blood in him. But certainly, his teachings are very consistent with some of the main themes of the Celtic Christian tradition, and he very importantly sees Earth consciousness and woman consciousness as inseparably related, and I think this is one of the things that the Celtic tradition has to offer for this moment in time. So much of the leadership of our Western world especially has been under a type of shadow masculine energy that has arrayed itself up over against Earth, but also, over against the feminine. I think the Celtic tradition very beautifully holds together this reverence for the feminine and reverence for Earth.

Do you think that Celtic spirituality is in danger of corruption?

Do you think that Celtic spirituality is in danger of corruption?

Yes, I think that there is some. There has been a type of romanticism about the Celtic that I think has not been true to its historical roots. I understand the enormous appeal to a tradition that is moving towards a sort of reverence for earth, and a reverence for every human being. But it has, in some expressions, toppled into a type of romanticism that, I think, misses the real heart wisdom of this tradition. Certainly, if we look at the great teachers that have articulated vision in the Celtic world over the centuries, these are not people who are naive to add to the struggle, to the suffering and the pain. So, I think, in its heart, this is a tradition that is very robustly aware of just how broken we are, and how infected the body of earth is at this moment in time. There’s no way forward through romanticism. I mean, I love Hildegard of Bingen. She’s another one of these figures in whom we see so much resonance with the Celtic, and it’s interesting, of course, that she trained at a Celtic monastic community. But I love when she says we need to learn to fly with two wings of awareness. One is the awareness of life’s glory and beauty, and the other is the awareness of life’s brokenness and suffering. She says, if we try to fly with only one of those wings of awareness, we’re like an eagle trying to fly with only one wing. In other words, we won’t ascend a true height of perspective if we want to bury our heads in the sand in relation to just how broken we are, and how capable of falseness we are. I think the heart of the tradition is very robust and strong on that front. But I think part of the more popular appeal of the Celtic is that it goes soft, it goes sort of limitedly romantic, and I think loses real strength of soul when it does that.

I am conducting a book-study using Sacred Earth, Sacred Soul. It is fantastic. I am in Tucson, AZ. Do you have any plans for doing a workshop either close to Tucson or on Zoom? I have “you” on the top of my Bucket List and I sure would love to make this wish come true! Blessings on you and your work. Sandi