While most travellers probably head to Québec City and Old Québec for the unique Frenchness of the place, I found myself on a recent visit getting more interested in the area’s surprising Irishness. My wife Linda and I were camped out in a stylish and comfortable loft on Rue Sainte-Ann right across from City Hall and above a noisy late-night bistro that pumped out floor-thumping rap music. It was almost winter, although tolerably warm for a town that soon would host public tobogganing, ice skating, and room rentals in makeshift ice hotels.

On a previous visit, we had hiked around the Plains of Abraham on skull-numbing cold days, with me pondering that title of Alistair MacLeod’s’ brilliant novel, No Great Mischief. According to the author, the phrase referred to a statement by British General James Wolfe who, during the Battle of Québec in 1759, had this to say about his Scottish Highland soldiers: “No great mischief should they fall.” Wolfe was dismissively referring to the fact that these warriors were expendable, as soldiers so often are, but that because of their origins, they were more expendable than most.

I had seen enough war paraphernalia and tales of military history in Québec on that foray so, this time round, I was looking for new perspectives on this unique Francophone city. That led Linda and I first back to a wonderful little cave-like pub in Lower Town called Pub L’Oncle Antoine where we had sat and supped on a previous visit. To us, it had seemed both genuine and local, warm and welcoming and (to my mind) the pinnacle of French-Canadian culture. Perhaps it had changed hands since last we darkened Antoine’s door, but this time round it was nearly empty, the music was soulless and bad, the beer was tolerable, but they were out of French onion soup. Sometimes it doesn’t work to return to favoured haunts as travellers. We all know that.

So, here was a good reminder that we should be looking for something new and undiscovered to us about Québec City. Still saddened by the dearth of French onion soup, we set off wandering the streets looking for signs and surprises. Over the next few days, we meandered in ever widening concentric circles outward from our third story encampment and, along the way stumbled upon a prominent historical marker on Rue McMahon titled “Irish Roots in Old Québec: The Irish Settle and Flourish.”

The truth be told, both Linda and I had been pining for another trip to Ireland ever since the Covid pandemic had curbed our more-or-less regular visits to the Emerald Isle. So, I was now determined to discover whatever I might about the Irish of Québec City. I remembered that I had read somewhere that nearly half a million residents of the province of Québec declared some portion of Irish ancestry. And most certainly, wherever the Irish immigrated to, there were dramatic, fascinating but often tragic stories. I was especially curious about the “flourish” aspect of the story. Clearly, I had some research to do. So, I was now fully engaged and gleaned from this helpful sidewalk marker the following: “History notes that the first Irish in Québec City were soldiers in the French army and, later, soldiers and officers of the British garrison. By 1815, the newcomers were mostly Protestant businesspeople and craftsmen. Around I830, Irish immigrants were mainly Catholic and of more modest means. Massive emigration from Ireland, which was plagued by famine and disease, was a phenomenon of the 1840s. By 1871, some 12,500 Québec City citizens were of Irish origin.”

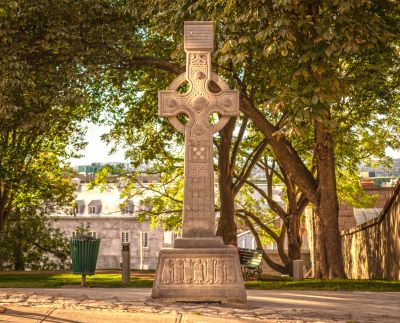

For me, this was all uncharted territory, and then further exploration took us to a rather prominent Celtic cross in Artillery Park. To me, it now seemed clear that I was fated to find out a bit more about the history of the Irish of this city before leaving town. According to Parks Canada, “The cross, sculpted by Aileen Brannigan from blue limestone in the Feelystone quarries, incorporates elements sacred and profane; mythological and scriptural; historical and legendary.”

For me, this was all uncharted territory, and then further exploration took us to a rather prominent Celtic cross in Artillery Park. To me, it now seemed clear that I was fated to find out a bit more about the history of the Irish of this city before leaving town. According to Parks Canada, “The cross, sculpted by Aileen Brannigan from blue limestone in the Feelystone quarries, incorporates elements sacred and profane; mythological and scriptural; historical and legendary.”

Just like the Irish to combine the profound and the profane in a handsome stone monument.

I decided to dip into the past by discovering who McMahon was and why the street was named for him. I soon learned that Patrick McMahon was a prominent Catholic priest in the 1800s who promoted and supported Irish emigration to Quebec. He was also of considerable service to that Irish community, especially during the multiple disasters of the 1840s. I didn’t have to dig much deeper to realize that this story of Irish immigration was fraught with suffering and tragedy. McMahon also was responsible for overseeing the construction of St. Patrick’s Church named not for him but for the familiar patron saint of Ireland.

Any self-respecting historian might have headed straight off to that very sanctuary to have a look, but as we ambled on, we came across St. Patrick Irish Pub on Rue Saint-Jean and stopped for drink and nourishment. It was a noisy, festive establishment and there was Guinness to be had, but I must admit it didn’t feel terribly authentic. This came as no particular surprise. I’d walked into quite a number of “Irish pubs” in various parts of the world and most seemed to be designed to satisfy what most non-Irish think an Irish pub should look like. (My personal favourite pubs in rural Ireland tend to have fake wood luan paneling on the walls, scuffed linoleum floors with a sleeping dog or two, surly barkeeps, and a couple of locals discussing football scores.) Here, however there was a path to the loo marked with shamrock stickers on the floor and a downstairs music venue with a solitary afternoon folk singer hammering out a serviceable version of “The Rocky Road to Dublin.” So clearly, some version of Irish culture flourished within these walls even if that pint of Guinness now cost $12 which would have caused many a dead Irish immigrant to roll over in their grave.

Back in our loft overlooking City Hall, I got a bit more serious about my research and soon discovered that the interrelationship of the Irish and the French in continental Europe was considerable, including quite a number of Irish chiefs and soldiers living in exile in France way back in the 16th century.

Consulting the Ville de Quebec website and leaping ahead a few centuries, I read that, “Half of the immigrants who landed in Québec in the first two decades of the 19th century were of Irish origin. Most were Protestants who belonged to the wealthier classes of society.” The rosy story changes considerably after that, as farm workers and their families left Ireland in the thousands hoping to establish a better life. Those who made it to Quebec City settled in Lower Town and men found jobs loading and unloading freight from ships on the docks of the St. Lawrence.

On yet another chilly morning, Linda and I revisited Lower Town, stopping to take a signature selfie along with a throng of tourists at the top of Breakneck Steps and then elbowing our way through the crowds of shoppers along Rue du petit Champlain. Apparently the twentieth and twenty first centuries had squeezed most of the Irish influence out of this historic but glamorized urban zone, but the preserved stone architecture remains impressive. From there we ventured further onward to the river and the ports, crossing several roadways with heavy traffic, hoping to get some glimpse of where those Irish longshoreman slaved away for shipping magnates in cruel conditions bad enough to prompt them to form one of Canada’s fist labour unions. Alas, all we found were bigger highways, more traffic and a generic industrial dockside landscape that could have been in any city in North America.

Later that day, I read more about the 1840s, when Irish immigrants sailed across the Atlantic and up the St. Lawrence escaping the terrible potato famine of their home country. Conditions in many of these vessels were appalling with diseases spreading rapidly aboard ship.

Over 17,000 of those refugees heading to Quebec City in 1847 alone died in transit or upon arrival.

For good reason, those vessels were often referred to as “coffin ships.” I thought it would be proper to visit the grave site of so many of those who died trying to make it to Canada, but I soon realized that would require a trip to Grosse Isle, 46 kilometres downstream from Quebec City and only accessible by boat or plane. The island is today a national historical site and has its own proper Celtic Cross monument built by the Ancient Order of Hibernians commemorating the losses of the Irish who died from typhus in 1847-1848.

According to The Canadian Encyclopedia,” In 1832, the deserted island was turned into a quarantine station for immigrants, to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, in particular cholera…Despite these efforts, a cholera epidemic spread to Quebec City and Montreal in 1832 and 1834 causing thousands of deaths.”

Things got much worse starting in the spring of 1847 when those escaping the Great Potato Famine began arriving with typhus, often referred to as “ship fever.” A total of 441 ships were headed for Quebec City and hundreds upon hundreds died during the voyages, many of whom were dumped overboard during the crossing. Dr. George Douglas was the medical authority of the quarantine station there, charged with dealing with those who survived, but well over 5,000 died and were buried at Grosse Ile.

To add to such misery, there were as many as six epidemics of cholera in Quebec City itself between 1832 and 1854 where many more Irish immigrants died. According to Ville de Quebec, “The Irish first joined with French Canadians in the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul to help Irish immigrants struggling with illness and poverty. Then they created an institution of their own to help orphans, the destitute, and the elderly…The progressive integration of Québec City’s Irish community into the French-Canadian majority was eased by the religion they shared: 90 per cent were Catholic at the start of the 20th century.”

Before we left the city, I paid my respects once more to the Celtic cross on Rue McMahon, somewhat enlightened about the history of the Irish here, sobered by the sadness of such pain, suffering and loss. I realized that many cities along the Atlantic seaboard had similar tragic histories of immigration. Later that night, in a comfortable hotel room near the airport in Montreal, my thoughts were haunted mostly about what conditions must have been like on those “coffin ships.”

Not quite ready to move on to happier prospects, I went looking for answers only to find excerpts from Robert Whyte’s book, The 1847 Famine Ship Diary: The Journey of a Coffin Ship. Observing the conditions of passengers on board, he noted that many “’were to be left enveloped in reeking pestilence, the sick without medicine, medical skill, nourishment, or so much as a drop of pure water.” There were happier days ahead for those who survived in the “flourishing” Irish-Quebec communities, but the human price paid for a new life in Canada in the nineteenth century was extremely high. As an immigrant to Canada myself in the twentieth century, I feel blessed that the only impediments in my path was a problematic and obstinate bureaucracy that eventually relented and let me into this fine country.

lesleychoyce.com

I enjoyed your article on the Irish in Quebec. Both my husband and I have Irish ancestors and were able to acquire our Irish Citizenship through descent. The sad history of Ireland reminds me how resilient people can be…Your article has given us more insight and we hope to visit Quebec City again very soon.