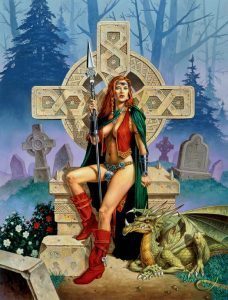

Queen Medb of Connacht is arguably the most famous female character in Irish mythology. Her story is told in the Cattle Raid of Cooley, or Táin Bó Cúailnge in Irish. In it, she competes with her husband, Aillil, over which of them possesses the greatest wealth, and demands the use of Donn Cúailnge, the big brown bull belonging to neighbouring King Dáire mac Fiachna. When he refuses, she has no hesitation in leading her armies into battle to get it.

We may never know how accurate this portrayal of Medb is, but it does indicate that in ancient Ireland, not only could women be Queens, but they could lead armies, be warriors and druids, possess wealth and property in their own right, and engage in marriage on an equal footing with their husbands.

The Brehon Law corroborates this. According to legend, High King Cormac mac Airt was responsible for collating all the laws from oral tradition and establishing the Brehon Law. Cormac did not come to power until his thirtieth year, by which time he was already well known for his wisdom.

Brehon means ‘official lawgiver, ’and the profession which handled matters of law were known as brithem, which means ‘judge’. In the fifth century, St. Patrick distilled these laws down to five volumes, removing and discarding those which did not fit with Christian doctrine. These tomes were known collectively as the Senchas Mór. English rule in the seventeenth century finally banished these laws once and for all, replacing them instead with their own feudal system.

The Brehon Law was a system well ahead of its time. It was all about equality and democracy and was based on a complex system of fines instead of corporal punishment. It covered everything from matters of commerce, crime, healthcare, the ownership of property to marital and family law, and equal rights.

Women were entitled to enter all the same professions as men; they could be Druids, poets, physicians, lawgivers, teachers, warriors, leaders, even Queens. The mythological stories are littered with such references to women of power.

For example, when Nuada led the Tuatha de Danann in their invasion of Ireland, his wife Macha fought fiercely at his side in both Battles of Moytura. In fact, in the second battle, when Nuada fell under the Fomori Giant-King Balor’s sword, she stood over his body and protected him as well as she could before she too was struck down. Macha is also credited as being part of the triad of the Morrigan, warrior Goddess of battle, strife and sovereignty.

It is interesting to note that Ireland’s two most legendary mythical heroes, Cuchullain and Fionn mac Cumhall were both taught their warrior skills by women.

Cuchulain travelled to the home of Scathach, a female teacher of the battle arts, who lived on an island off the coast of Alba (Scotland). Her fame had spread far and wide, and many came to her to study and hone their military skills. She had, however, made an enemy in the form of Aoife, a former student. On one occasion, Cuchulain took Scathach’s place in a contest of single combat against Aoife, seemingly unfazed at the prospect of fighting a woman.

Fionn mac Cumhall was raised in secret in the forests of the Slieve Bloom mountains by his Druidess aunt, Bodhmall, and warrior woman, Liath Luachra. When Bodhmall had taught him all the druid lore she knew, Fionn continued his studies with the Druid Finegas on the banks of the River Boyne. Liath Luachra means ‘Gray of Luachair’, but there is very little known about her, other than that she taught Fionn how to hunt and fight, both skills for which he was renowned and unmatched. Clearly, she did a good job.

Like Cuchulain, Fionn also had quite an astonishing battle with a woman. She was Ogermach, fierce warrior-daughter of the King of Greece, and had sailed with Daire Donn, King of the World, to invade Ireland. They fought long and hard before Fionn finally succeeded in striking off her head.

The Goddess Brigid is another example of the power of the female. Not only was she well known for her healing skills, but she was also renowned for her poetic prowess, and patron of the forge, not commonly thought of as ‘women’s work’.

Airmid was also a famous healer. Born into a medical family of the Tuatha de Denann, she was daughter of Dian-Cecht, Nuada’s physician. It was he who replaced Nuada’s arm with a replacement of silver, when the king was injured in battle. Dian-Cecht’s son, Miach, was eventually able to grow skin over the metal contraption, a feat his father was so jealous of, he attacked and killed his own son.

Airmid’s skills lay in herbal lore. She collected and studied all the herbs of Ireland, categorising them according to their medicinal properties. Unfortunately, her father came and scattered all her herbs far and wide, so that her hard won knowledge was lost.

Women could be lawgivers, too. Brigid Brethach (Brigid of the Judgements), also known as Ambue, the ‘cowless’ or ‘propertyless’, served King Conchobar mac Nessa as his lawyer. She was said to have granted women the right to inherit land from their fathers, and was also associated with various other women’s causes in ancient law.

Irish mythology is liberally sprinkled with tales of the deeds of Female Druids; Biróg is a Druidess who, in one version of the myth, was involved in saving the baby Lugh from being drowned by his grandfather, Balor; Tlachtga was the daughter of Mog Ruith, a powerful blind sorcerer, associated with the Hill of Ward and the November 1st fire festival of Samhain; Bé Chuille was a Danann Druidess who was involved in the defeat of Carman, the Celtic witch; Queen Medb was warned by the Danann Druidess and Seer, Fedelma, of the defeat of her army.

Unlike much of the rest of the ancient world, where women were considered pretty much as their husbands’ property, the women of Ireland enjoyed equal status in marriage with their husbands.

Unlike much of the rest of the ancient world, where women were considered pretty much as their husbands’ property, the women of Ireland enjoyed equal status in marriage with their husbands.

She retained possession of all her own properties that she brought with her to the marriage. She had the right to divorce him, if he did not fulfill his marital obligations, and if she so, she was entitled to take with her all her own possessions and half of their joint property, plus a portion for damages.

We know from the stories we have inherited that men and women frequently chose lovers, and perhaps changed marriage partners just as often. There seems to have been no stigma in this. We can’t be sure that marriages were even intended as life-long commitments then, as they are today. Take, for example, the tradition of ‘hand-fasting’, which in Ireland dates back to the Tailten Games originally set up by Lugh to honour the death of his foster mother, Tailtiu.

Young men and women would line up either side of a wall so that neither side could see the other. The girls would put their hand through a hole in the wall, and the man waiting on the other side would take it. This indicated their promise to live together as man and wife for a year and a day. If the marriage didn’t work out, they attended the next Tailten Fair for a deed of separation. Then, if they so desired, they were free to try their luck again.

Medb herself had several husbands and many lovers. The Goddess Boann, after whom the River Boyne is named, had an affair with the Dagda while she was still married to Elcmar. She became pregnant with his son, Aengus. In order to conceal the pregnancy, the Dagda stopped the sun in the sky which made the day last nine months, so that in effect, Aengus was conceived, gestated and delivered all in one day.

High King Cormac mac Airt gave his daughter, Deirdre, in marriage to the aging Fionn mac Cumhall in order to cement their alliance. Although she agreed, she changed her mind pretty quickly when she met the far younger, handsome and charming Diarmuid, for she eloped with him on the very night of her wedding to poor Fionn.

Leave a Comment